Charter School Performance in

New York City

October 2017

2

© 2017 CREDO

Center for Research on Education Outcomes

Stanford University

Stanford, CA

http://credo.stanford.edu

CREDO, the Center for Research on Education Outcomes at Stanford University, was established to

improve empirical evidence about education reform and student performance at the primary and

secondary levels. CREDO at Stanford University supports education organizations and policymakers in

using reliable research and program evaluation to assess the performance of education initiatives.

CREDO’s valuable insight helps educators and policymakers strengthen their focus on the results from

innovative programs, curricula, policies and accountability practices.

Acknowledgements

CREDO gratefully acknowledges the support of New York State Education Department (NYSED) who

contributed data support and assistance to this partnership. Our data access partnerships form the

foundation of CREDO's work, without which studies like this would be impossible. We strive daily to

justify the confidence placed in us.

The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent the positions or policies of the organizations

noted above. No official endorsement of any product, commodity, service or enterprise mentioned in

this publication is intended or should be inferred. The analysis and conclusions contained herein are

exclusively those of the authors, are not endorsed by any of CREDO’s supporting organizations, their

governing boards, or the state governments, state education departments or school districts that

participated in this study. The conclusions of this research do not necessarily reflect the opinions or

official position of the New York Education Agency, or the State of New York.

3

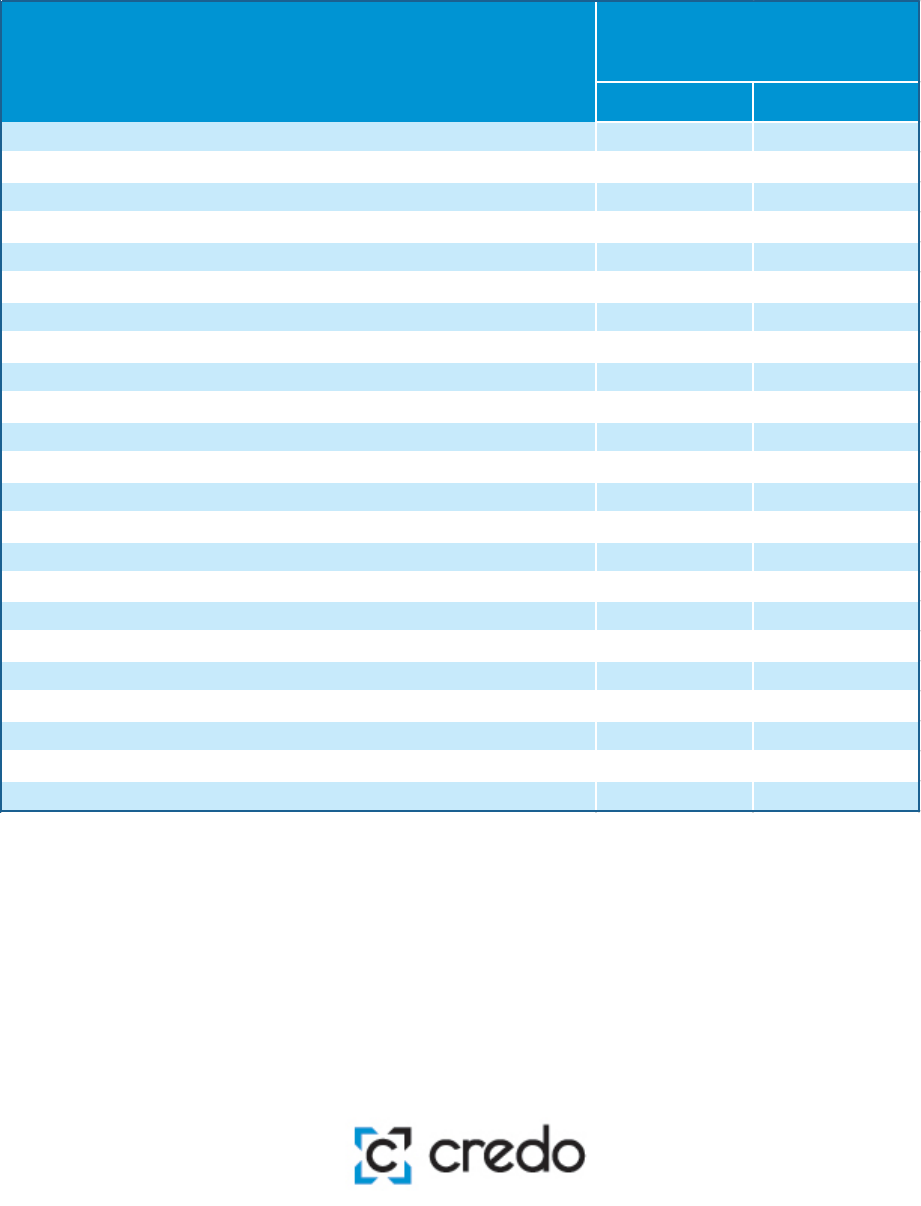

Table of Contents

Introduction ................................................................................................................................................. 7

Study Approach ............................................................................................................................................ 8

New York City Charter School Demographics ........................................................................................... 12

Overall Charter School Impact .................................................................................................................. 15

Charter School Impact for the 2011-2015 Cohort ..................................................................................... 17

Charter School Impact by Growth Period ................................................................................................. 18

Charter School Impact by School Level .................................................................................................... 18

Charter School Impact by Students’ Years of Enrollment ........................................................................ 20

Charter School Impact by Race/Ethnicity ................................................................................................. 22

Charter School Impact with Students in Poverty ..................................................................................... 27

Charter School Impact with Race/Ethnicity and Poverty ......................................................................... 29

Charter School Impact with Special Education Students ........................................................................ 32

Charter School Impact with English Language Learners ......................................................................... 33

School–level Analysis ................................................................................................................................. 36

Impact of Charter Management Organizations ........................................................................................ 40

Impact of Charter School Networks .......................................................................................................... 45

New York City High School Graduation Rate ............................................................................................ 47

Synthesis and Conclusions ........................................................................................................................ 49

Implications ................................................................................................................................................ 51

Technical Appendix .................................................................................................................................... 55

Table of Contents

4

Figure 1: CREDO Virtual Control Record Methodology ............................................................... 10

Figure 2: Opened and Closed Charter Campuses, 2011 to 2015 ................................................... 12

Figure 3: Average Learning Gains in New York City Charter Schools Compared to Gains for VCR

Students .............................................................................................................................. 15

Figure 4: Comparison of 2013 and 2017 New York City Study ..................................................... 17

Figure 5: Impact by Growth Period, 2013-2016 ......................................................................... 18

Figure 6: Impact by School Level ............................................................................................. 19

Figure 7: Impact by Students’ Years of Enrollment .................................................................... 20

Figure 8: Learning Gains of Black Students Benchmarked Against Learning Gains of White TPS

Students .............................................................................................................................. 23

Figure 8a: Relative Learning Gains for Black Charter School Students Benchmarked Against their

Black TPS Peers .................................................................................................................. 234

Figure 9: Learning Gains of Hispanic Students Benchmarked Against Learning Gains of White TPS

Students .............................................................................................................................. 25

Figure 9a: Relative Learning Gains for Hispanic Charter School Students Benchmarked Against their

Hispanic TPS Peers .............................................................................................................. 256

Figure 10: Learning Gains of Students in Poverty Benchmarked Against Learning Gains of TPS

Students not in Poverty ......................................................................................................... 27

Figure 11: Learning Gains of Black Students in Poverty Benchmarked Against Learning Gains of

White TPS Students not in Poverty .......................................................................................... 29

Figure 11a: Relative Learning Gains for Black Charter School Students in Poverty Benchmarked

Against their Black TPS Peers in Poverty ............................................................................. 3029

Figure 12: Learning Gains of Hispanic Students in Poverty Benchmarked Against Learning Gains of

White TPS Students not in Poverty .......................................................................................... 31

Table of Figures

5

Figure 12a: Relative Learning Gains for Hispanic Charter School Students in Poverty Benchmarked

Against their Hispanic TPS Peers in Poverty ........................................................................... 312

Figure 13: Learning Gains of Special Education Students Benchmarked Against Learning Gains of

TPS Students not in Special Education .................................................................................... 33

Figure 14: Learning Gains of ELL Students Benchmarked Against Learning Gains of Non-ELL TPS

Students .............................................................................................................................. 34

Figure 15: Average Student Learning Gains of CMO Charter Schools and Non-CMO Charter Schools

Benchmarked Against the Statewide Average TPS Student Learning Gains ................................. 41

Figure 15a: Relative Student Learning Gains of CMO Charter Schools Benchmarked Against Learning

Gains of Non-CMO Charter Schools ........................................................................................ 411

Figure 16: CMO and Non-CMO Student Learning Gains by School Level Benchmarked Against TPS

Learning Gains by School Level .............................................................................................. 43

Figure 16a: Relative Learning Gains of Students in CMOs by School-Level Benchmarked against

Learning Gains of Non-CMO Charter School Students by School Level ....................................... 433

Figure 17: New York City High School Graduation Rate (Cohorts 2009 to 2012) ............................ 47

Figure 18: Overall NYC Schools versus NYC Charters: Regents and Advanced High School Graduation

Rates (Cohorts 2010 to 2012) .................................................................................................. 48

6

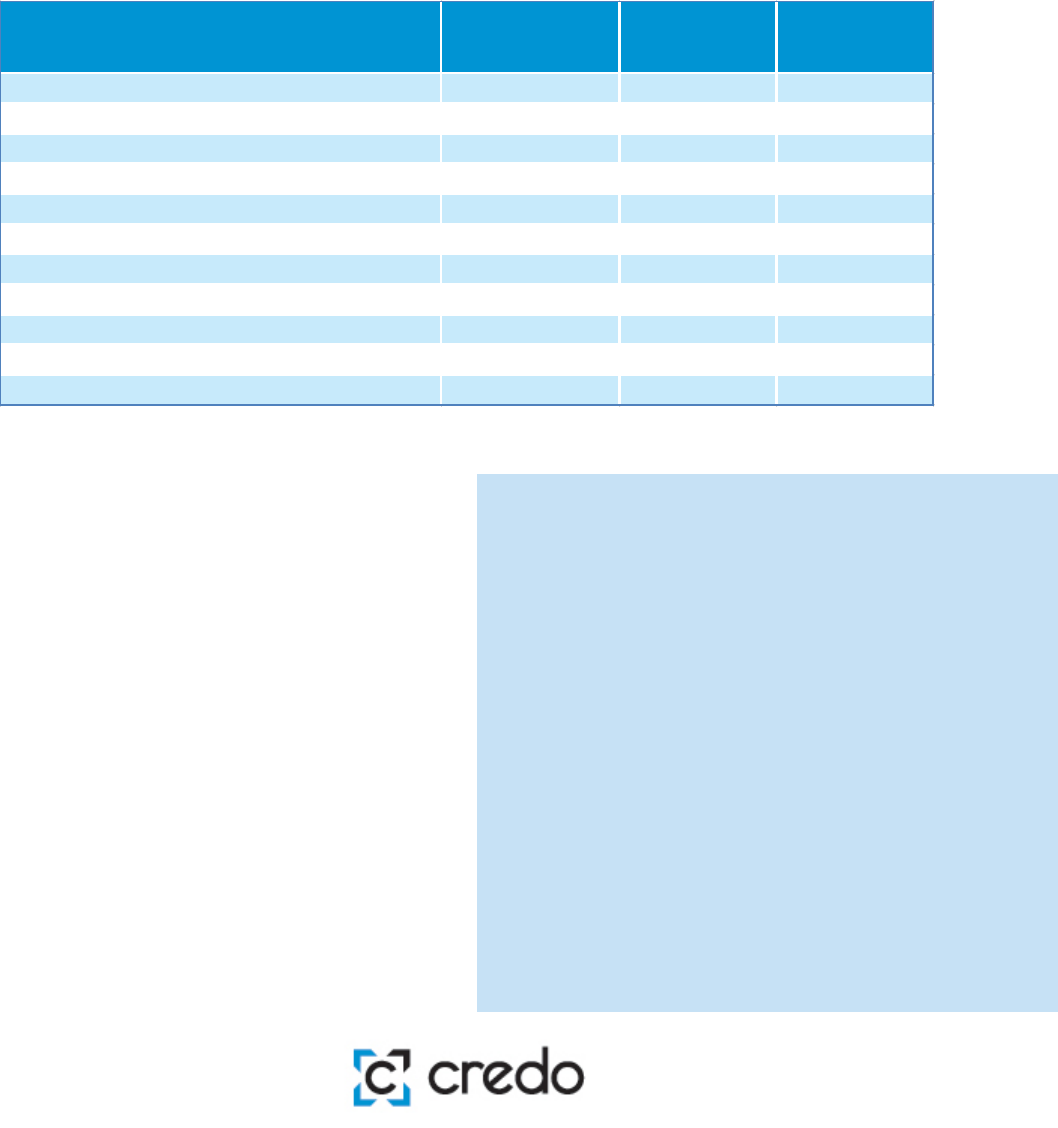

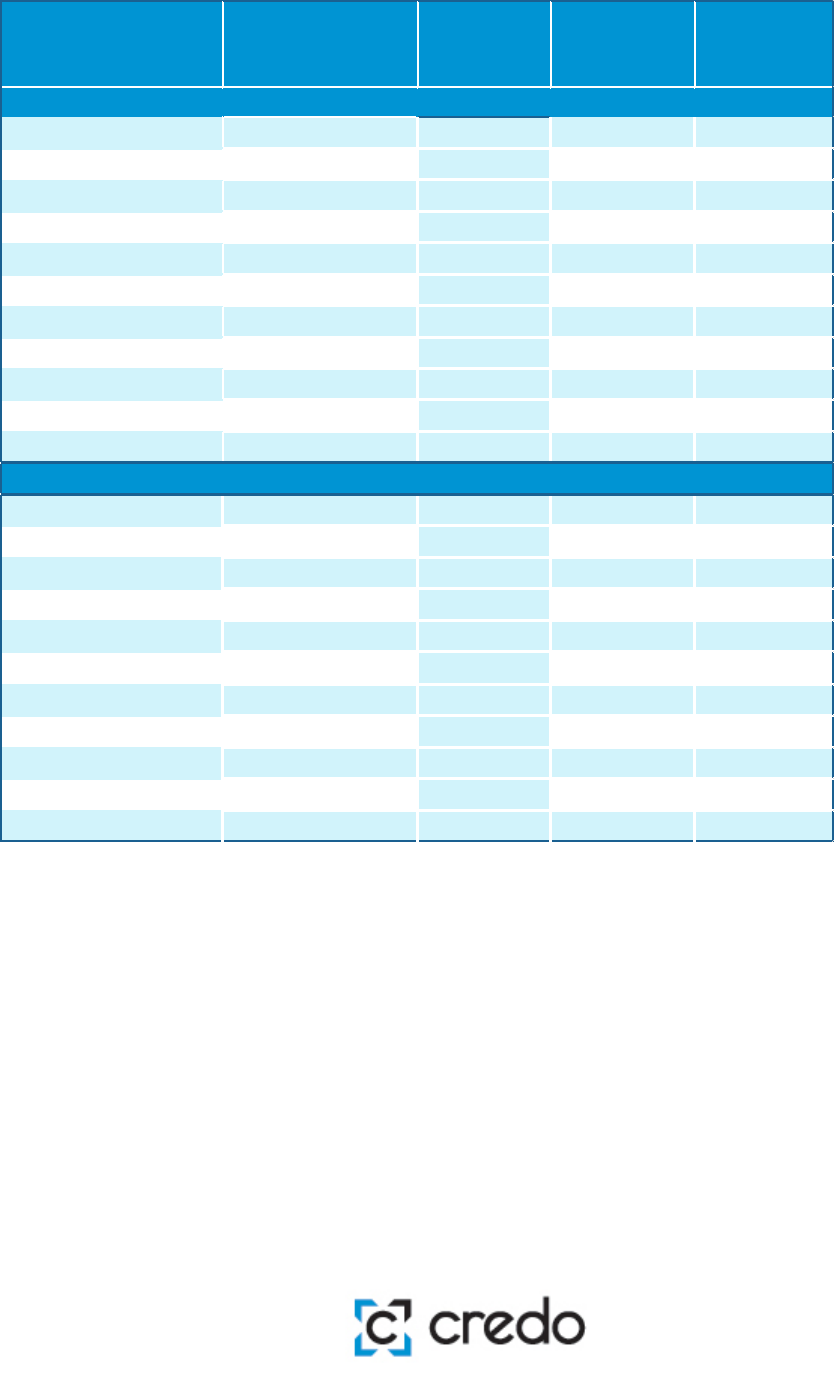

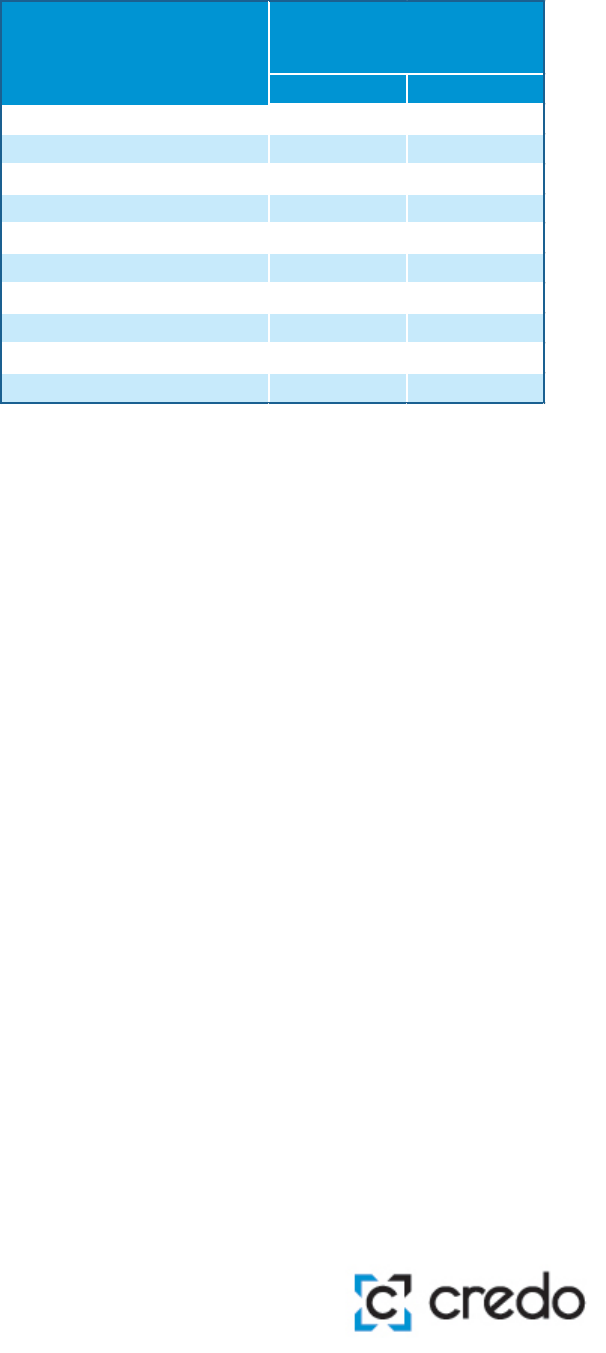

Table 1: Demographic Comparison of Students in TPS, Feeders and Charters (School Year 2015-16) . 13

Table 2: Demographic Composition of Charter Students in the Study ........................................... 14

Table 3: Transformation of Average Learning Gains in Reading and Math ...................................... 16

Table 4: Performance of Charter Schools Compared to Their Local Schools in New York City ........... 36

Table 5: Reading Growth and Achievement ............................................................................... 38

Table 6: Math Growth and Achievement .................................................................................... 39

Table 7: Performance of Charter School Networks in New York City based on Growth Effect Size ...... 46

Table 8: Summary of Statistically Significant Findings for New York Charter School Students .......... 52

Table of Tables

7

Introduction

New York City has been the nexus of public discourse about charter schools for nearly two decades.

Charter school advocates praise the sector as providing important parental choice through the

introduction of different educational models of instruction. Opponents contend that their existence is

antithetical to the traditions of public education and produce at least as much harm as good. Despite

the voluminous attention to the topic, only a fraction of that debate is grounded in well researched

evidence about charter schools’ impact on student outcomes. This report contributes to the discussion

by providing evidence for charter students’ performance in New York City over five years of schooling,

beginning with the 2011-2012 school year and ending in 2015-2016.

The current study was supported by the Achelis-Bodman Foundation and the Walton Family

Foundation. With the cooperation of the New York State Education Department (NYSED), CREDO

obtained the historical sets of student-level administrative records. The support of NYSED staff was

critical to CREDO's understanding of the character and quality of the data we received. However, the

entirety of interactions with the Department dealt with technical issues related to the data. CREDO has

developed the findings and conclusions presented here independently.

This report provides an in-depth examination of the results for charter schools in New York City. This

current report has two main benefits. First, it provides a rigorous and independent view of the

performance of the city’s charter schools. Second, the study design is consistent with CREDO’s reports

on charter school performance in other locations, making the results amenable to benchmarking both

nationally and in other locations.

The analysis is presented here in three parts. We first present findings about the effects of charter

schools on student academic performance. These results are expressed in terms of the academic

progress that a typical charter school student in New York City would realize from a year of enrollment

in a charter school. To help the non-technical reader grasp the findings, we translate the scientific

estimates into estimated days of learning based on the foundation of a 180-day school year.

The second set of findings is presented at the school level. Both legislation and public policy operate to

influence school level decisions. These findings look at the performance of students by school and

present school average results.

8

The third set of analyses examines the performance of charter schools grouped by charter school

networks. In New York City, as in the rest of the nation, charter schools networks are comprised of either

charter management organizations, education management organizations, or a combination of both.

These analyses aim to discern whether there are differences between schools that are part of these

charter networks versus charter schools that are independent.

The results of our analysis show that there is overall improvement in the performance of New York City

charter schools. Compared to the educational gains that charter students might have had in a

traditional public school (TPS), the analysis shows that in a year's time, on average, charter school

students in New York City show stronger growth in both reading and math. The impact is statistically

significant: thinking of a 180-day school year as "one year of learning", an average New York City charter

student demonstrates growth equivalent to completing 23 additional days of learning in reading and

63 additional days in math each year. When the findings are disaggregated to examine student sub-

groups, the analysis reveals that several subgroups exhibit stronger growth than their TPS peers while

others do not. Notable growth occurs among Hispanic and Black charter students in poverty, who post

stronger growth compared to their counterparts in TPS, during the period of the study. Overall, over

the four growth periods of the study, charter students demonstrate positive growth in both subjects

with the exception of reading in the 2014-2015 growth period. At the final period of the study, there is

statistically significant growth in both reading and math.

Study Approach

This study of charter schools in New York City focuses on the academic progress (growth) of enrolled

and tested students in New York City charter schools. Whatever else charter schools may provide their

students, their contributions to their students’ readiness for secondary education, high school

graduation, and post-secondary life remains of paramount importance. Indeed, if charter schools do

not succeed in forging strong academic futures for their students, it is unclear whether social and

emotional skills can compensate. Furthermore, current data limitations prevent the inclusion of non-

academic outcomes in this analysis.

This city-wide analysis uses the Virtual Control Record (VCR) methodology that has been used in

previous CREDO publications.

1,2,3

The approach is a quasi-experimental study design with matched

student records that are followed over time. The current analysis examines whether students in charter

1

Cremata, Edward, D. Davis, K. Dickey, K. Lawyer, Y. Negassi, M. Raymond and J.Woodworth. National Charter

School Study 2013 (2013). http://credo.stanford.edu.

2

CREDO Urban Charter School Study (2015).

http://urbancharters.stanford.edu/download/Urban%20Charter%20School%20Study%20Report%20on%2041

%20Regions.pdf

3

Woodworth, James, K. Chirbas, M. Gonzalez, Y. Negassi, M. Raymond W. Snow, and C. VanDonge. Online Charter

School Study (2015). https://credo.stanford.edu/pdfs/Online%20Charter%20Study%20Final.pdf.

9

schools in New York City outperform their traditional public school (TPS) counterparts. This general

question is then extended to consider whether the observed charter school performance is consistent

when the charter school population is disaggregated along a number of dimensions, such as

race/ethnicity and years enrolled in a charter school. Answers to these questions require that we ensure

that the contribution of both the charter schools and the traditional public schools – is isolated from

other potentially confounding influences. Accordingly, these analyses include many other variables

whose purpose is to prevent the tainting of the estimate of charter schooling by other effects. The

analysis includes controls for student characteristics: prior academic achievement, race/ethnicity,

special education status, lunch program participation, English proficiency, grade level, and retention

in grade.

To create a reliable comparison group for our study, we strive to build a VCR for each charter school

student. A VCR is a synthesis of the actual academic experiences of students who are identical to the

charter school students, except for the fact that the VCR students attend a TPS that each charter

school’s students would have attended if not enrolled in their charter school. We refer to the VCR as a

‘virtual twin’ because it consolidates the experience of multiple ‘twins’ into a single synthesis of their

academic performance. This synthesized record is then used as the counterfactual condition to the

charter school student’s performance.

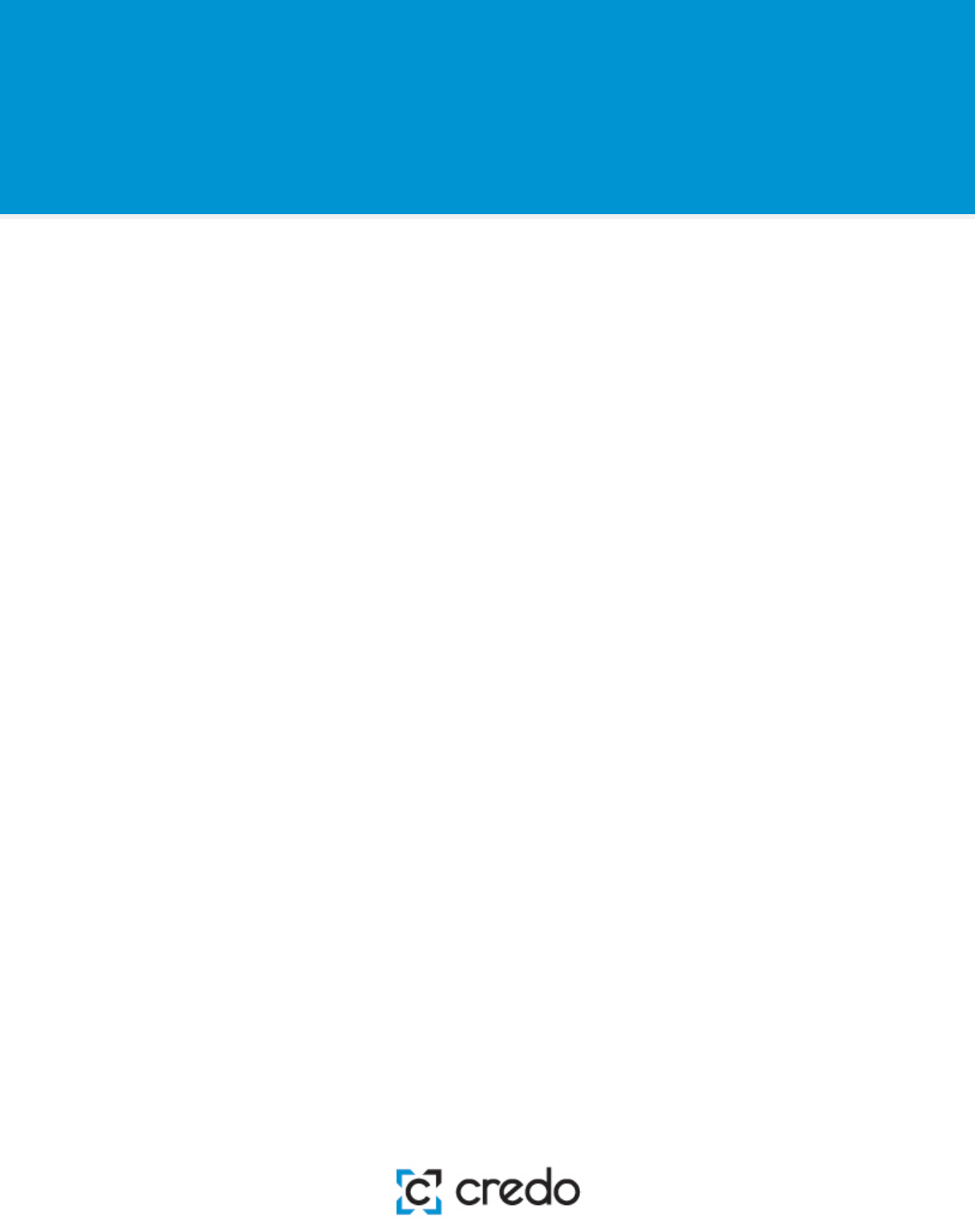

Our approach is displayed in Figure 1. We identify all the traditional public schools whose students

transfer to a given charter school; each of these schools is designated as a “feeder school.” Once a TPS

qualifies as a feeder school for a particular charter school, all the students in the school become

potential matches for a student in that particular charter school. All the student records from all the

feeder schools are pooled – this becomes the source of records for creating the virtual match. Using the

records of the students in those schools in the year prior to the test year of interest (t

0

), CREDO selects

all of the available TPS students that match each charter school student.

Match factors include:

• Grade level

• Gender

• Race/Ethnicity

• Free or Reduced Price Lunch Status

• English Language Learner Status

• Special Education Status

• Prior test score on New York state achievement tests

10

Figure 1: CREDO Virtual Control Record Methodology

At the point of selection as a VCR-eligible TPS student, all candidates are identical to the individual

charter school student on all observable characteristics, including prior academic achievement. The

focus then moves to the subsequent year, t

1

. The scores from this test year of interest (t

1

) for as many

as seven VCR-eligible TPS students are then averaged and a Virtual Control Record is produced. The

VCR produces a score for the test year of interest that corresponds to the expected result a charter

student would have realized had he or she attended one of the traditional public schools that would

have enrolled the charter school's students. The VCR thus provides the counterfactual "control"

experience for this analysis.

For the purposes of this report, the impact of charter schools on student academic performance is

estimated in terms of academic growth from one school year to the next. This increment of academic

progress is referred to by policy makers and researchers as a “growth score” or “learning gains” or “gain

11

scores.” Using statistical methods, it is possible to isolate the contributions of schools from other social

or programmatic influences on a student's growth. Thus, all the findings that follow are reported as the

average one-year growth of charter school students relative to their VCR-based comparisons.

With five years of student records in this study, we create four periods of academic growth. Each growth

period needs a "starting score", (i.e., the achievement test score from the spring of one year) and a

"subsequent score" (i.e., the test score from the following spring) to create the growth measure. To

simplify the presentation of results, each growth period is referred to by the year in which the second

spring test score is obtained. For example, the growth period denoted "2013" covers academic growth

that occurred between the end of the 2011-2012 school year and the end of the 2012-2013 school year.

Similarly, the growth period denoted "2016" corresponds to the year of growth between the 2014-2015

and 2015-2016 school years.

With five years of data, and six tested grades (3rd – 8th) as well as three end-of-course exams in math

(EOCs), there are over 40 different sets of data each for Reading and Math. Each subject-grade-year

group of scores (or, in the case of EOCs, subject-year group) has slightly different mid-point averages

and distributions. Test scores for all these separate tests are transformed to a common scale. All test

scores have been converted to "bell curve" standardized scores to allow year-to-year computations of

growth.

4

When scores are thus standardized into z-scores, every student is placed relative to his own peers in

New York City. A student scoring in the 50

th

percentile in New York City receives a z-score of zero, while

a z-score one standard deviation above that equates to the 84th percentile. Students who maintain

their relative place from year to year would have a growth score of zero, while students who make larger

gains relative to their peers will have positive growth scores. Conversely, students who make smaller

academic gains than their peers will have negative growth scores in that year. In this study it was

possible to create virtual matches for 79 percent of the tested charter school observations in reading

and 77 percent in math.

4

For each subject-grade-year set of scores, scores are centered around a standardized midpoint of zero, which

corresponds to the actual average score of the test before transformation. Then each score of the original test is

recast as a measure of deviation around that new score of zero, so that scores that fall below the original

average score are expressed as negative numbers and those that are larger receive positive values. These new

values are assigned such that in every subject-grade-year test, 68 percent of the original test scores fall within a

given distance, known as the standard deviation.

12

New York City Charter School Demographics

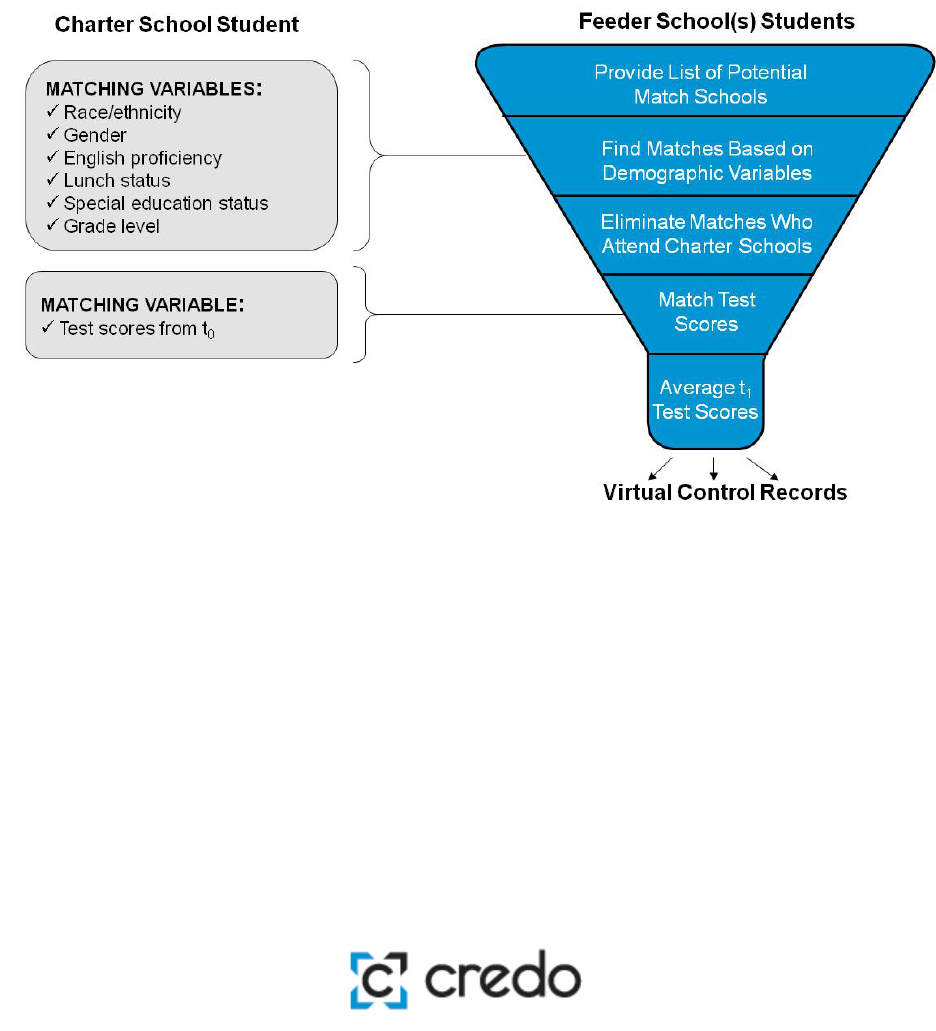

The collection of New York City charter schools has grown markedly since its inception in 1995. Figure

2 below notes the newly opened, continuing, and closed charter school campuses from the Fall of 2011

(the Fall of the first potential growth period for the current study) to the Fall of 2015 (the Fall of the last

potential growth period for the current study)

5

. According to the National Center for Education

Statistics (NCES), there were 231 charter schools open in New York City in the 2015-16 school year.

Figure 2: Opened and Closed Charter Campuses, 2011 to 2015

Because charter schools are able to choose their location, the aggregate demographics of the charter

schools may not mirror that of the NYC district schools as a whole. Further, charter schools may offer

different academic programs or alternate school models, which may disproportionately attract

particular groups of students relative to NYC district schools. In addition, parents and students who

choose to attend charter schools select schools for a variety of reasons, such as location, school safety,

small school size, academic focus, or special interest programs. The cumulative result of all these forces

is that the student populations at charters and their NYC district schools feeders may differ. Table 1

5

“Opened schools” opened as new schools in the fall of the displayed year. “Continuing schools” were opened

prior to the fall of the displayed year and remain open into the next school year (i.e. a school listed as continuing

in the 2015-16 column opened some time prior to 2015-16 and did not close in 2015-16) “Closed schools” cease

operation by the spring of the displayed year (i.e. a school listed as closed in the 2015-16 column had its last

year of operation in 2015-16 and closed at the end of that school year)

13

25

35

17

18

127

139

163

196

213

1

1

1

2

0

0

50

100

150

200

250

300

2011-12 2012-13 2013-14 2014-15 2015-16

# Opened

Continuing

# Closed

13

below compares the student populations in the 2015-2016 school year across three groups: all New

York City’s traditional public schools, those district schools that comprise the set of charter feeder

schools, and NYC charter schools in the aggregate. Table 1 includes the 197 charter schools in which

students took reading and/or math assessments during the 2015-16 school year. Note that NCES (cited

above) reports 231 charter schools open in New York City in 2015-16. The number of charter schools

listed in Table 1 is smaller than the NCES numbers because it excludes schools in which students were

not tested.

Table 1:

Demographic Comparison of Students in District, Feeders and Charters (School Year 2015-16)

The data from Table 1 show that the demographic profile of charter schools is quite different from that

of the public school population in New York City as

a whole. As shown in Table 1, the demographics

for the feeder schools more closely mirror the

district population than the population of

students in charters in New York City. The charter

school population in New York City differs from

both the New York City district and feeder

populations on several demographic variables.

Charter schools have more Black students and

fewer white, Hispanic and Asian/Pacific Islander

students than the public school population. The

proportion of Black students and students in

poverty enrolled in charter schools is noticeably

larger than in traditional public schools. Charters

and feeders both serve slightly more students in

poverty than TPS.

District

Feeders Charters

Number of schools 1637

1032 197

Average enrollment per school 586 618

427

Total number of students enrolled

958,726

637,706 84,179

Students in Poverty

72% 76% 76%

English Language Learners 14% 15%

6%

Special Education Students 21% 20% 17%

White Students 15%

13% 4%

Black Students

25% 28% 56%

Hispanic Students 41% 45%

36%

Asian/Pacific Islander Students 17% 12% 2%

Native American Students 1% 1% 1%

Graphics Roadmap

The graphics in this report have a common format.

Each graph presents the average performance of charter students

relative to their pertinent comparison student

. The reference

group differs depending on the specific comparison. Where a

graph compares student subgroup performance, the pertinent

comparison student is the same for both subgroups. Each graph is

labeled with the pertinent comparison group for clarity.

The height

of the bars in each graph reflects the magnitude of

difference between traditional public school and charter school

performance over the period studied.

Stars are used to reflect the level of statistical significance of the

differen

ce between the group represented in the bar and its

comparison group of similar students in TPS; the absence of stars

means that the schooling effect is not statistically different from

zero.

14

Policymakers and stakeholders focus on the degree to which underserved populations enroll in charter

schools. As shown in Table 1, 20 percent of feeder school students and 21 percent of NYC district

students have special education needs respectively. In contrast, 17 percent of the New York City charter

school population has a designated special education status. Similarly, a lower proportion of New York

City’s charter school population is designated as English language learners than the feeder schools or

district schools as a whole.

Table 2:

Demographic Composition of Charter Students in the Study

For this analysis, a total of 74,918 unique charter school students from 197 charter schools (141,322

observations across four growth periods) are followed for as many years as data are available.

6

The

students are drawn from grades 3 – 8, since these are the continuous grades covered by the New York

State achievement testing program for reading and math or by the state end-of-course assessments.

High school students are included for reading and math whenever they take the end-of-course

assessment sequence in consecutive years, e.g., Algebra I followed by Geometry or Algebra II in the next

year. An identical number of virtual comparison records are included in the analysis in each subject. In

New York City, it was possible to create virtual matches for 77 percent of the tested charter observations

in math and 79 percent in reading. This proportion assures that the results reported here can be

considered indicative of the overall performance of charter schools in New York City. The total number

of observations is large enough to have confidence that the tests of effect can detect real differences

between charter school and TPS student performance at the statistically acceptable standard of p<.05.

Each student subgroup examined also had an acceptable number of observations, as reported in Table

2. Additional descriptive demographics can be found in the Appendix.

6

Schools that opened recently or that only recently begun serving tested grades will not have four growth

periods of experience to include; however, these schools are still included in the analysis for the years in which

data are available

Number Percent Number Percent

New York City Charter Students 74,918 53,175

% Matched 53,175 71%

Black Students 41,889 56% 29,603 56%

Hispanic Students 27,765 37% 20,439 38%

White Students 2,502 3% 1,655 3%

Students in Poverty 57,267 76% 41,946 79%

Special Education Students 13,857 18% 8,074 15%

English Language Learners 3,162 4% 1,895 4%

Grade Repeating Students 4,943 7% 968 2%

Student Group

All Charter Students Tested

Matched Charter Students

15

Overall Charter School Impact

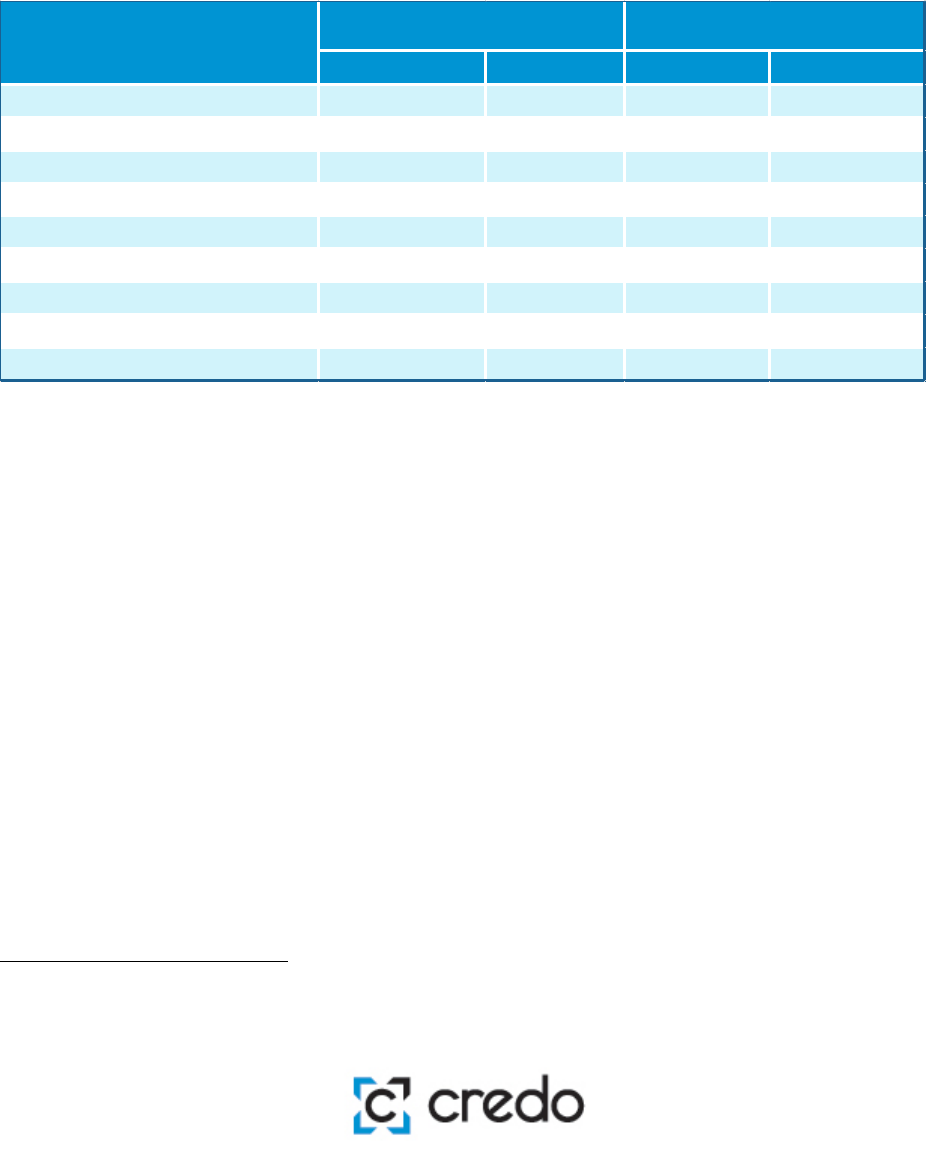

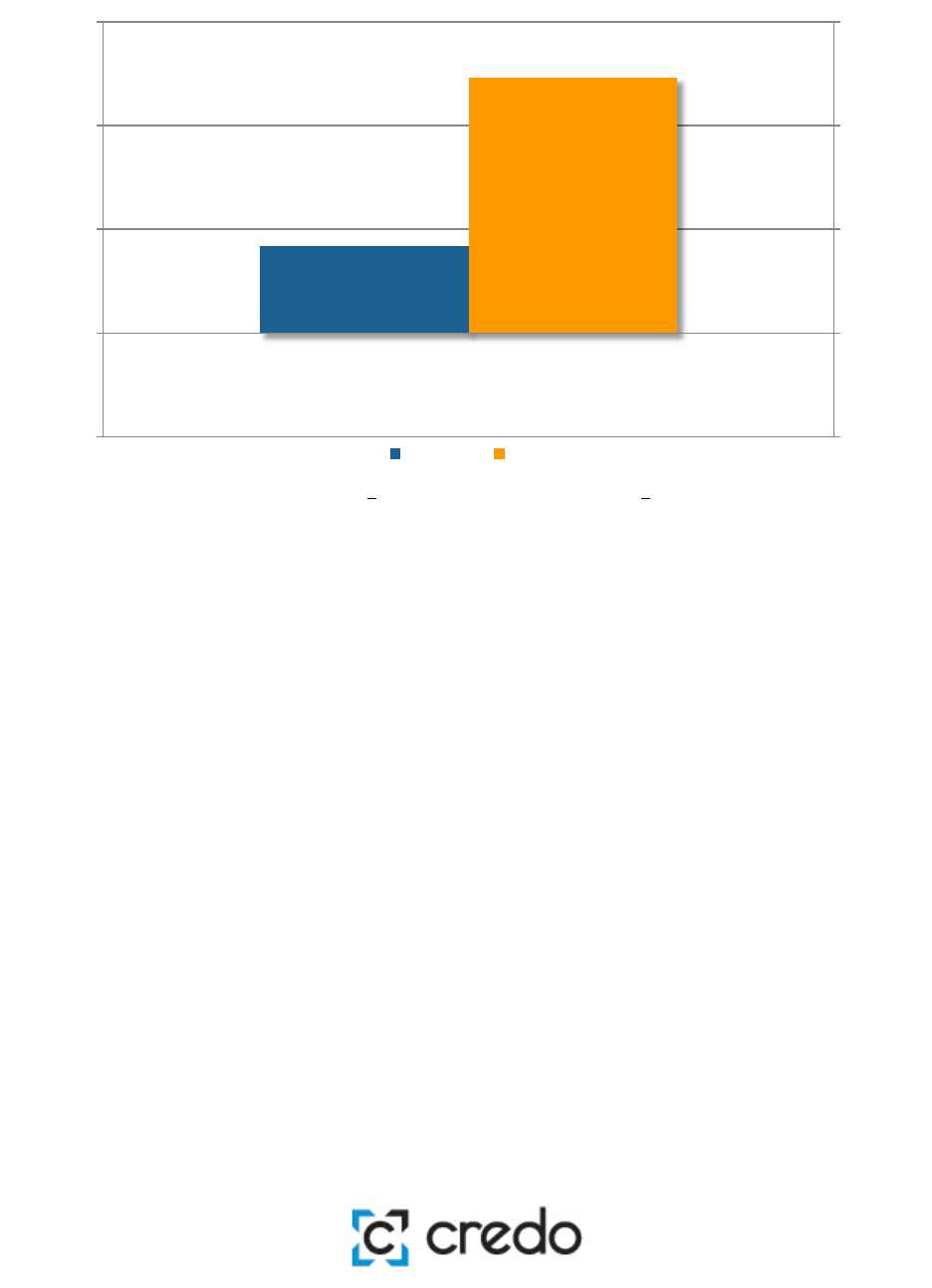

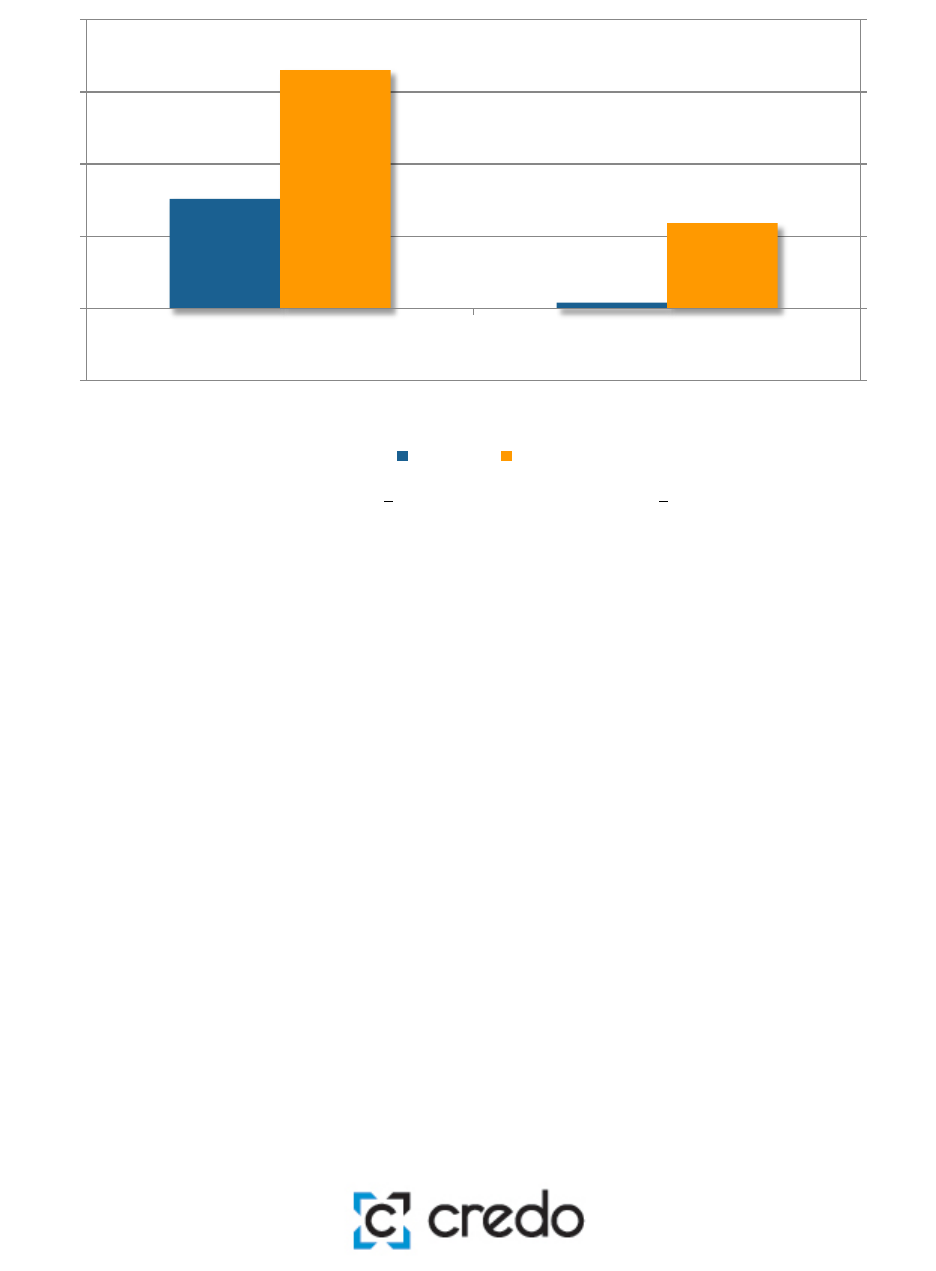

The first question is whether charter schools differ overall from traditional public schools in how much

their students learn, holding other factors constant. We average the pooled performance for all charter

school students across all four growth periods and compare this pooled performance with the same

pooled performance of the VCR students. Figure 3 displays the result, which is a measure of the typical

learning of charter school students in one year compared to their VCR peers from the feeder schools.

On average, students in charter schools in New York City learned more than students in TPS (the VCR

students) in both reading and math.

Figure 3: Average Learning Gains in New York City Charter Schools Compared to Gains for VCR Students

To obtain rigorous estimates, student growth data is analyzed in standard deviation units so that the

results can be assessed for statistical differences. Unfortunately, these units do not have much meaning

for the average reader. Transforming the results into more accessible terms is challenging and can be

done only with a number of general assumptions. Table 3 below, presents a translation of standard

deviation units to Days of Learning, but extreme values should be viewed with caution.

7

7

Hanushek, Eric A. P.E. Peterson, & L. Woessmann. Achievement Growth: International and U.S. State Trends In

Student Performance. Education Next, (2012) Vol. 12, 1–35.

.04**

.11**

-57

-29

0

29

57

86

-.10

-.05

.00

.05

.10

.15

Days of Learning

Growth (in standard deviations)

* Significant at p < 0.05 ** Significant at p < 0.01

Reading

Math

16

Table 3: Transformation of Average Learning Gains in Reading and Math

In order to understand “days of learning,” for a student whose academic achievement is at the 50

th

percentile in one grade and also at the 50

th

percentile in the following grade the next year, the progress

from one year to the next equals the average learning gain for a typical student between the two grades.

That growth is fixed as 180 days of effective learning based on the typical 180-day school year.

We then translate the standard deviations of growth from our models based on that 180-day average

year of learning, so that students with positive effect sizes have additional growth more than the

expected 180 days of academic progress in a year’s time and those with negative effect sizes have fewer

days of academic progress in that same 180-day period of time.

Using the results from Figure 3 and the transformations from Table 3 we can see that in a typical school

year, charter students in New York City exceed the growth of their TPS counterparts in reading and

math. This advantage for charter students is equivalent to 23 more days of learning in a 180-day school

year in reading and 63 days in math.

Growth

(in standard

deviations)

Gain

(in days of math

learning)

0.00 0

0.05 29

0.10 57

0.15

86

0.20 114

0.25 143

0.30 171

0.35

200

17

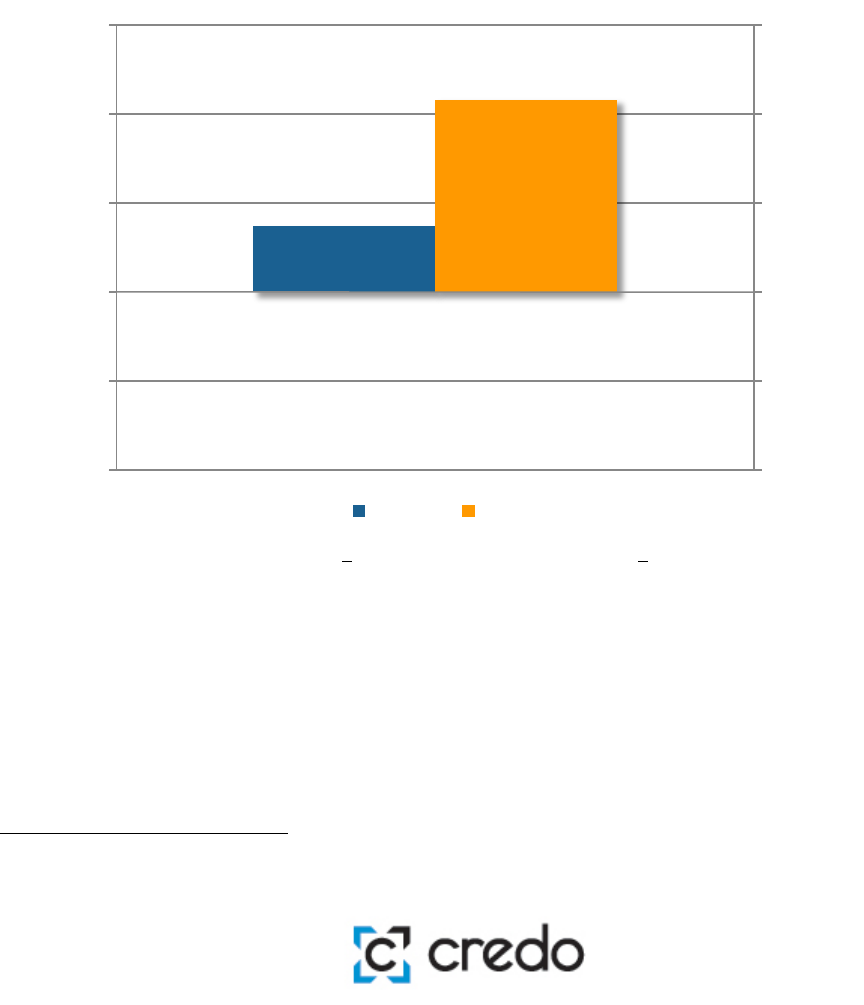

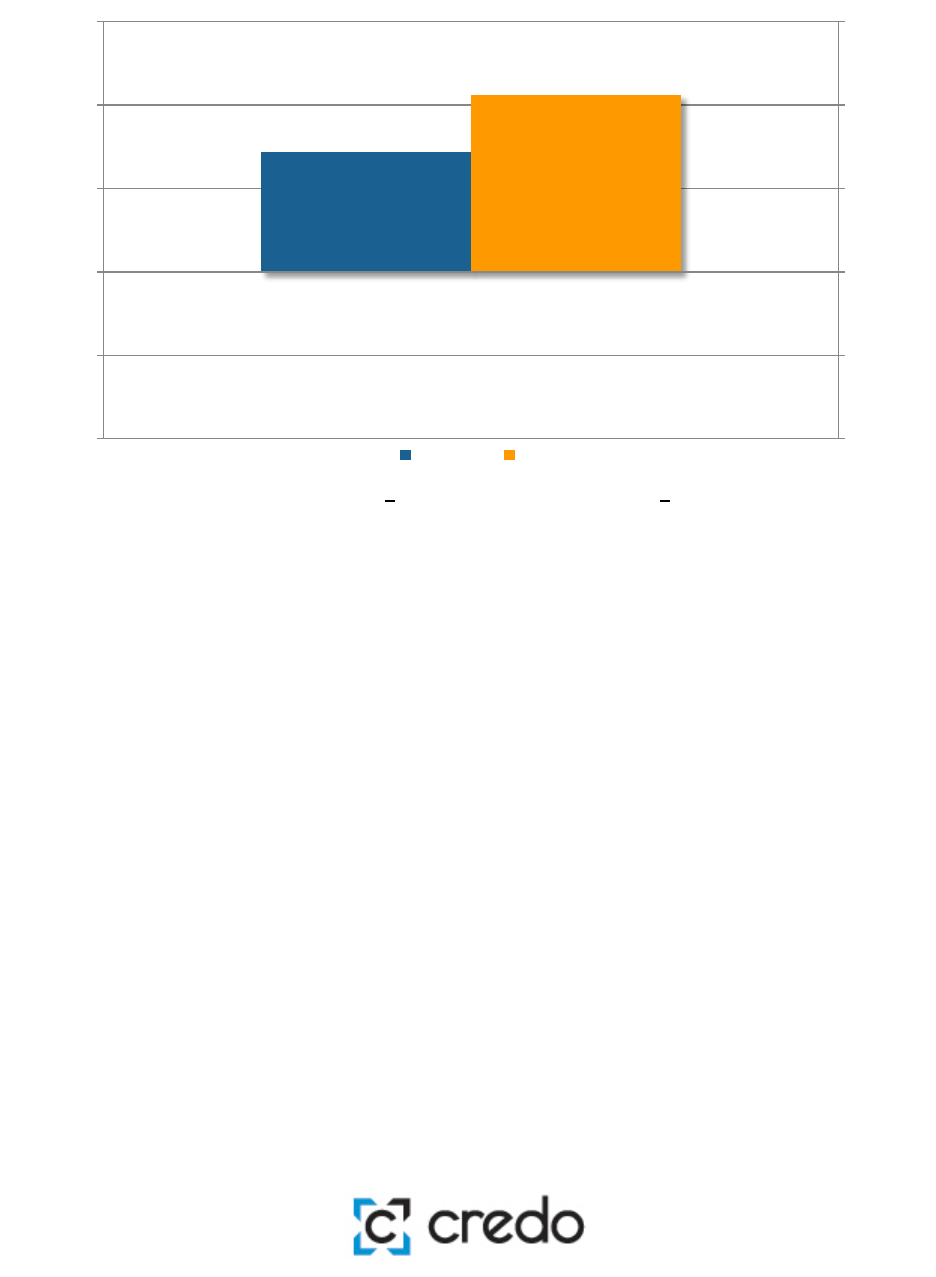

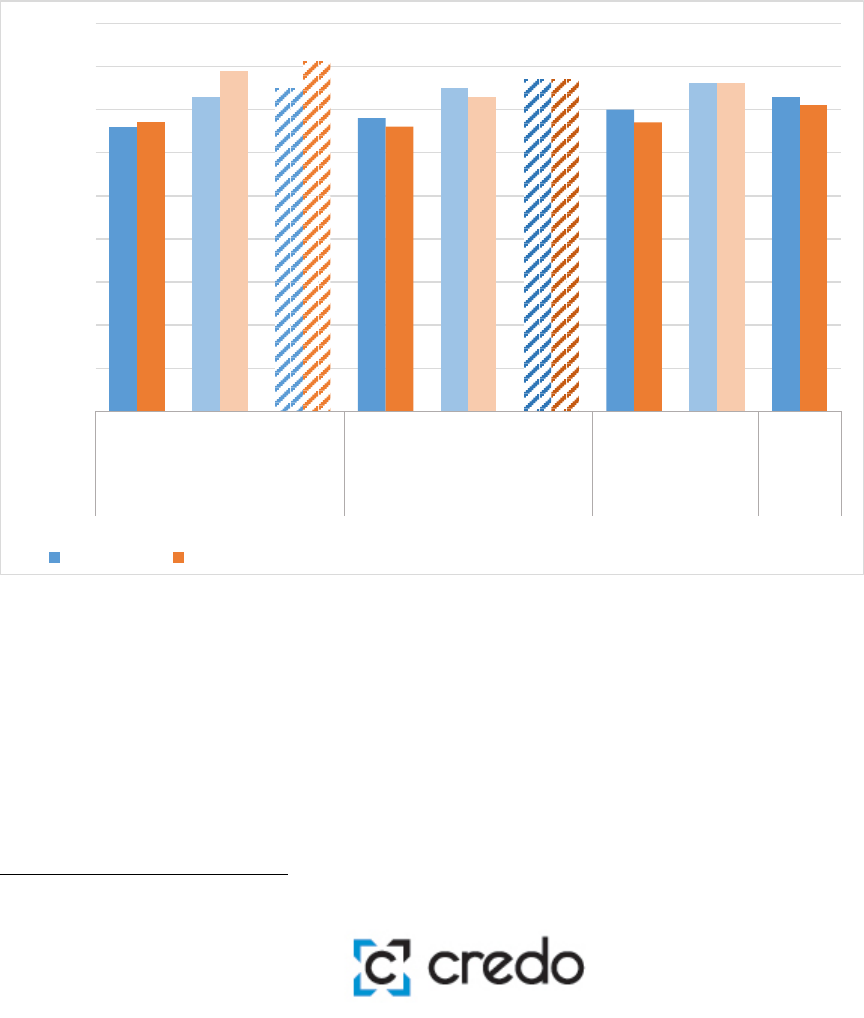

Charter School Impact for the 2011-2015 Cohort

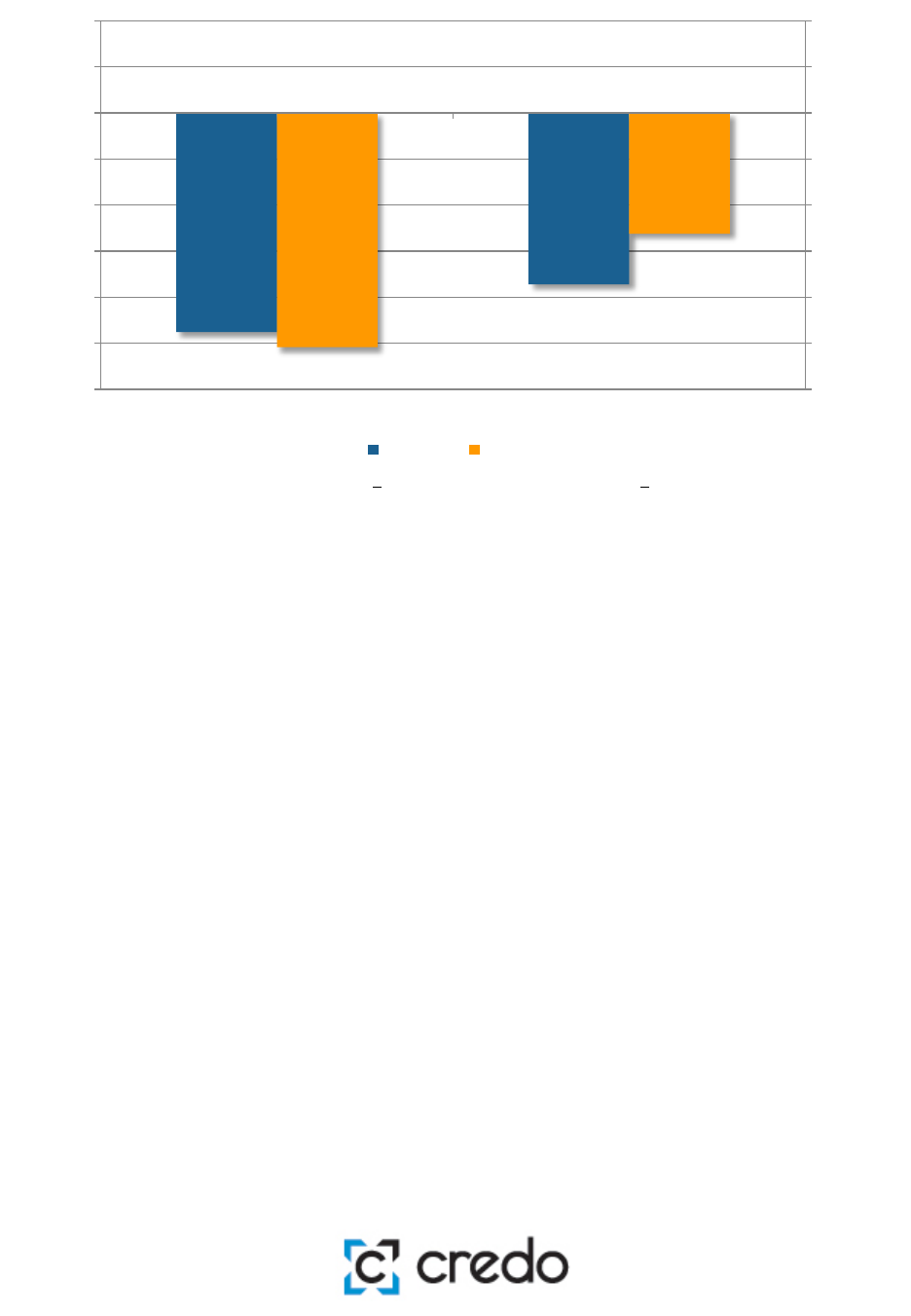

This section compares the results for New York City charter schools in the current study with earlier

results.

8

In 2013, CREDO released a study of New York City overall charter impact. The results of the

2013 CREDO study are displayed in the left column of Figure 4 and cover the 2005-2006 to 2010-2011

school years. The overall charter school impact found in this 2017 report is displayed in the right column

of Figure 4, covering the 2011-2012 to 2015-2016 school years.

Figure 4 shows that New York City charter schools have experienced slightly higher academic growth in

reading since the 2013 report. In math, charter school students’ academic growth fell since the 2013

study but remains strongly positive. These results translate to an annual gain of 6 more days of learning

in reading and 17 fewer days of learning per annum in math compared to the prior study results.

Figure 4: Comparison of 2013 and 2017 New York City Study

8

CREDO (2013). Charter School Performance in New York City. http://credo.stanford.edu.

.03**

.04**

.14**

.11**

-29

0

29

57

86

114

-.05

.00

.05

.10

.15

.20

Overall New York City 2013

Study

Overall New York City 2017

Study

Days of Learning

Growth (in standard deviations)

* Significant at p < 0.05 ** Significant at p < 0.01

Reading Math

18

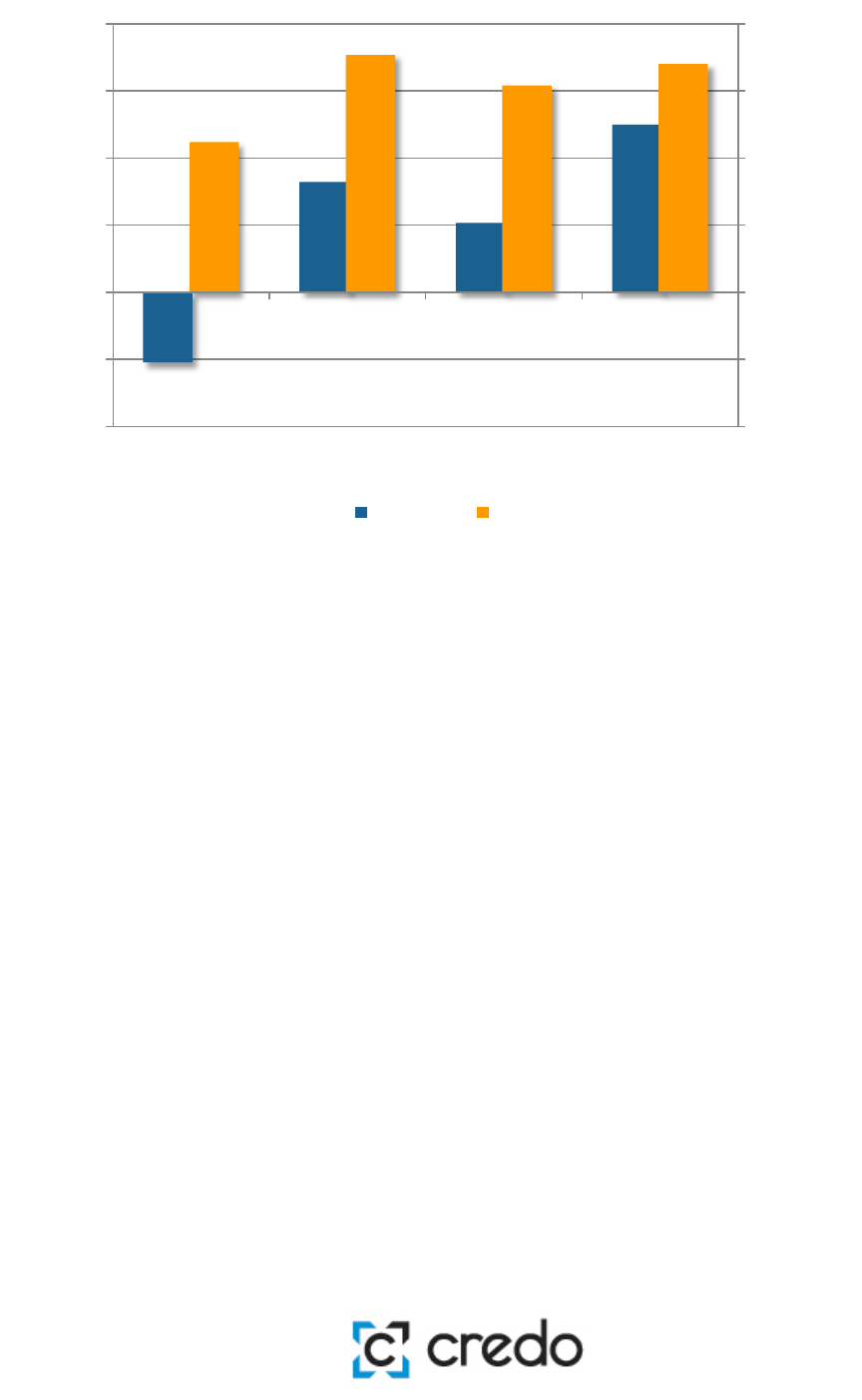

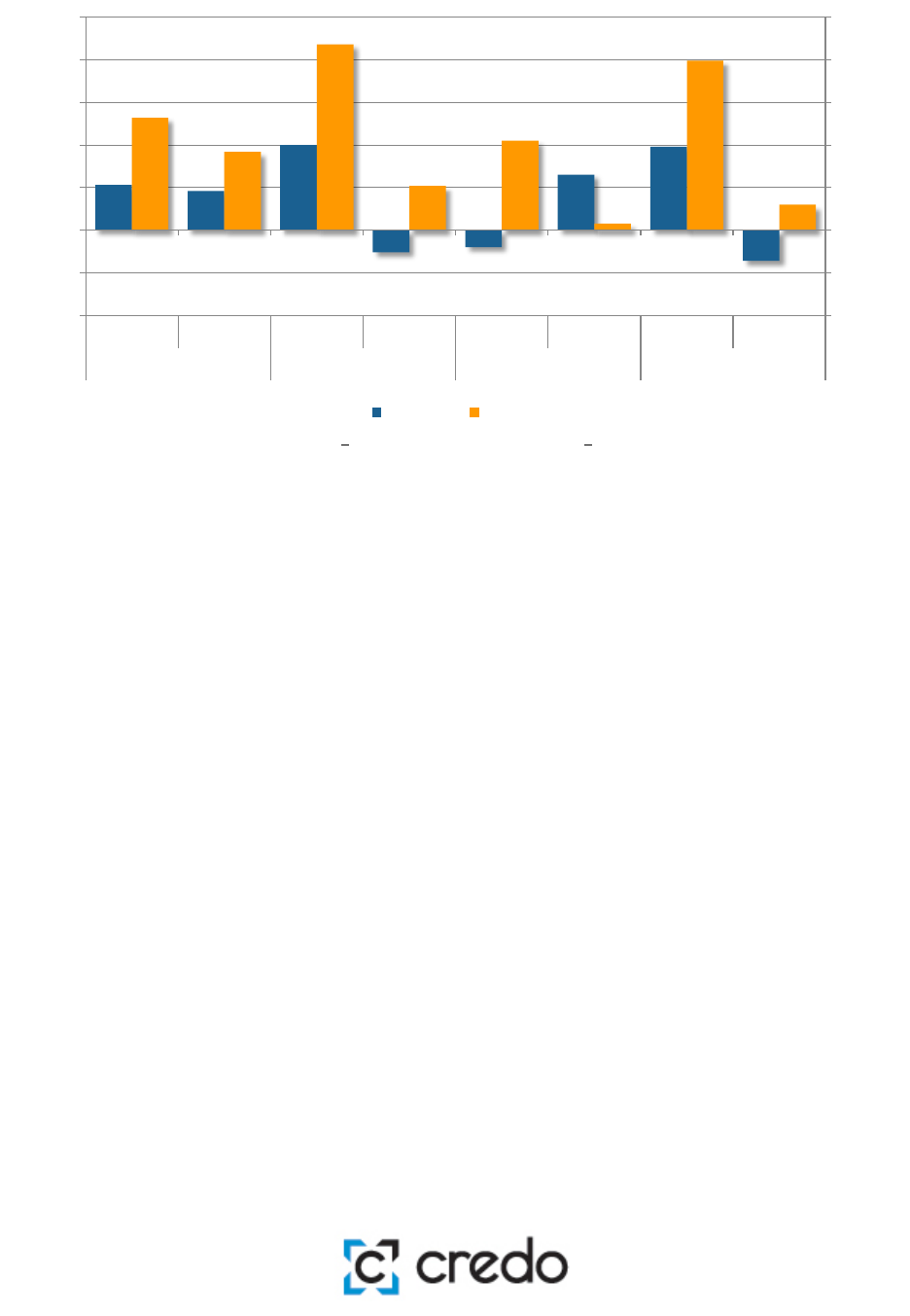

Charter School Impact by Growth Period

To determine whether performance remained consistent over all the periods of this study, the average

charter school effects were disaggregated into the four growth periods. Results are shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5: Impact by Growth Period, 2013-2016

The results depicted in Figure 5 suggest that there were significant gains in learning across the growth

periods for charter school students compared to their TPS peers in math. In reading, charter students

learned similarly to their peers in 2012-2013 and 2014-2015 growth periods; but out-performed TPS

peers in 2013-14 and 2015-16. The 2015-2016 growth period illustrates that charter students

experienced reading growth of approximately 51 more days of learning and 74 days of additional

learning in math compared to their TPS peers. In the 2015-16 growth period charter students see their

largest gains in both reading and math.

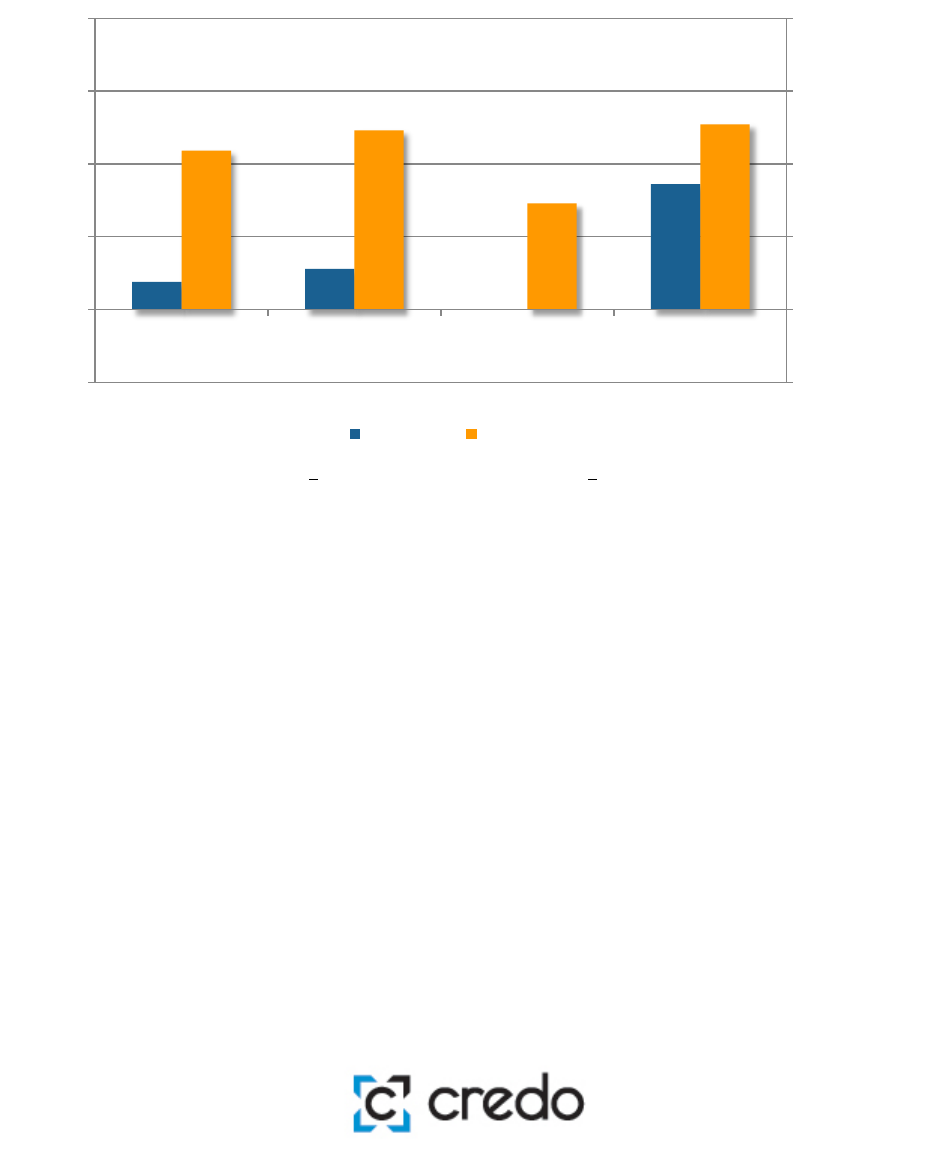

Charter School Impact by School Level

.02

.03* .00

.09**

.11**

.12**

.07**

.13**

-29

0

29

57

86

114

-.05

.00

.05

.10

.15

.20

2012-2013

2013-2014

2014-2015

2015-2016

Days of Learning

Growth (in standard deviations)

*Significant at p

< 0.05

** Significant at p

< 0.01

Reading Math

19

Charter schools are permitted to choose which grade levels to serve. Some charter operators focus on

particular ages, some seek to serve a full range of grades, and others build by adding one additional

grade each year. For example, multi-level charter schools serve grade ranges larger than traditional

elementary, middle or high schools. Such a configuration might contain a combination of middle and

high school grades. In New York City, schools are classified as multi-level if they serve both elementary

and secondary students. The National Center for Education Statistics identifies these schools. This

allows us to disaggregate charter school impacts for different grade spans

9

.

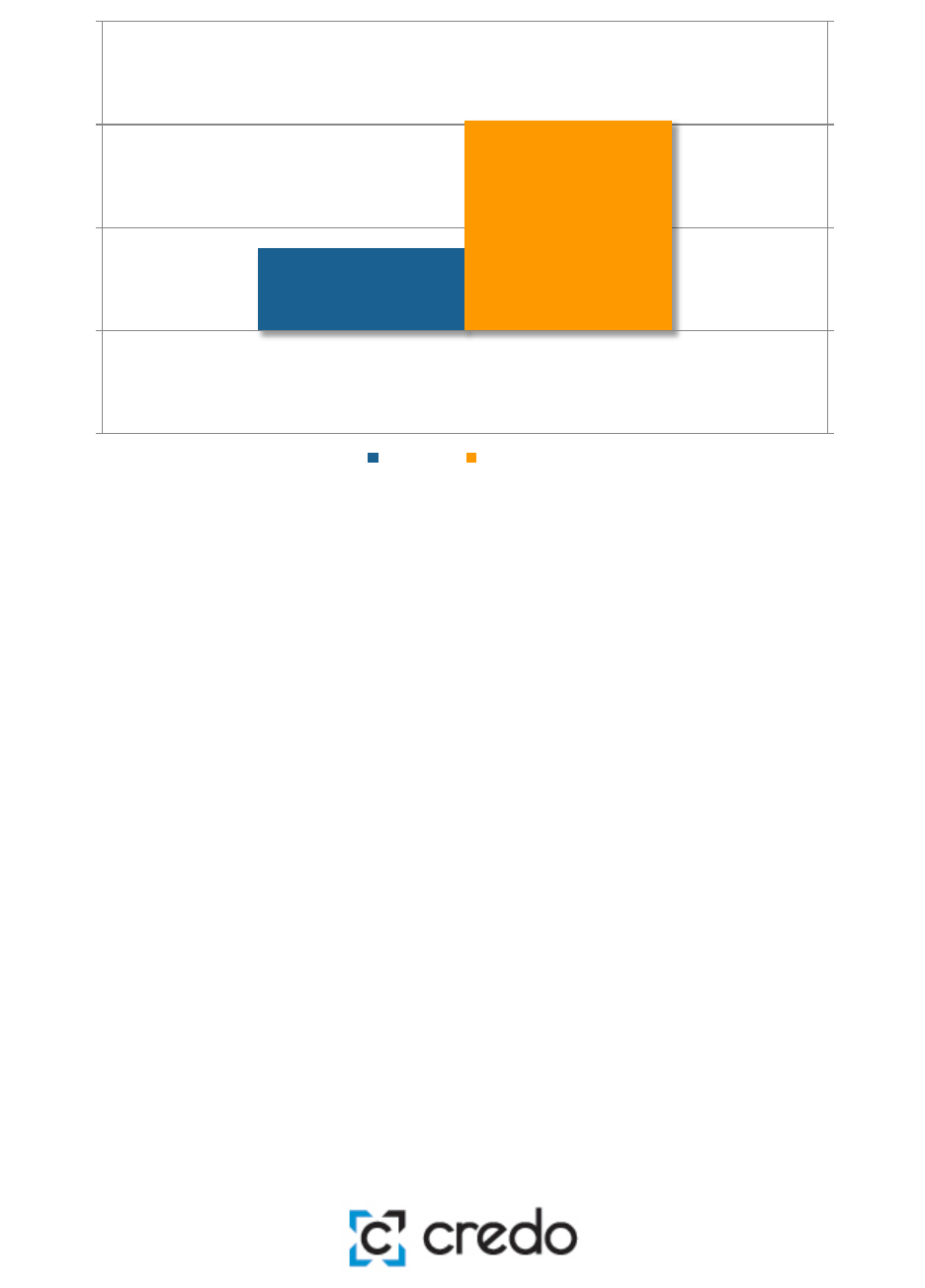

This study examines the outcomes of students enrolled in elementary, middle, high, and multi-level

schools. The results appear in Figure 6 below.

Figure 6: Impact by School Level

The results indicate that the strongest charter school performance is observed in elementary and multi-

level schools, where, on average, charter school students see stronger growth than their TPS

counterparts in reading and math. This growth translates to 29 extra days of learning in reading, for

both elementary and multi-level schools. In math, the growth translates to 63 additional days of

9

CREDO does not assign school levels, but rather retains school levels that are assigned to schools by the National

Center for Education Statistics. The sole exception is that CREDO considers a school to be a high school if the

lowest grade served is ninth grade or above.

.05**

.00

0.01

.05**

.11**

.09**

.06

.13**

-29

0

29

57

86

-.05

.00

.05

.10

.15

Elementary Middle High Multi-level

Days of Learning

Growth (in standard deviations)

* Significant at p < 0.05 ** Significant at p < 0.01

Reading Math

20

learning for elementary students and about 74 additional days of learning in multi-level schools.

Charter students in middle school show stronger growth in math than their TPS counterparts

translating to an additional 51 days of learning. Middle school charter students’ reading growth

remains similar to their TPS peers. High school charter students and high school TPS students exhibit

similar growth in both subjects.

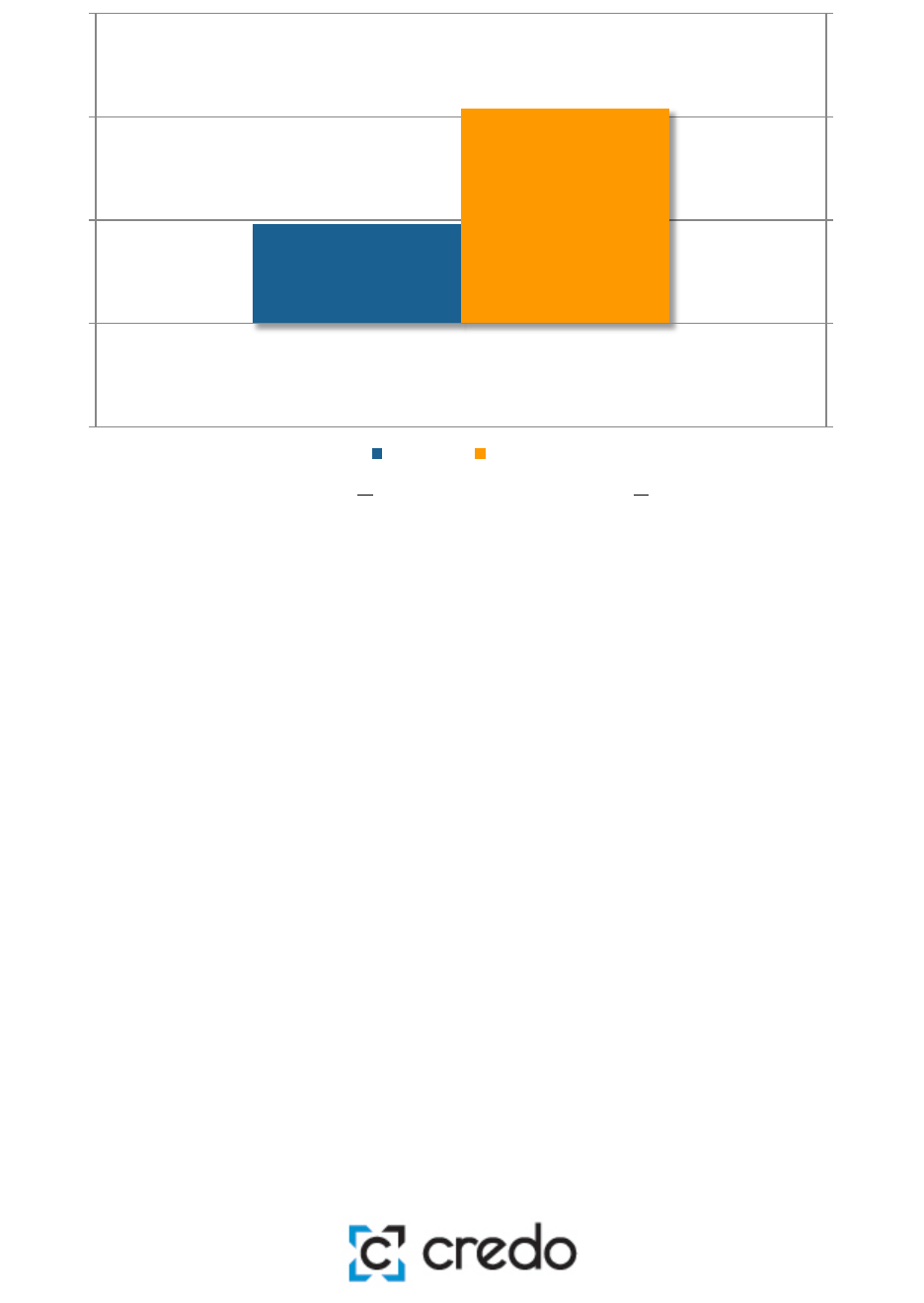

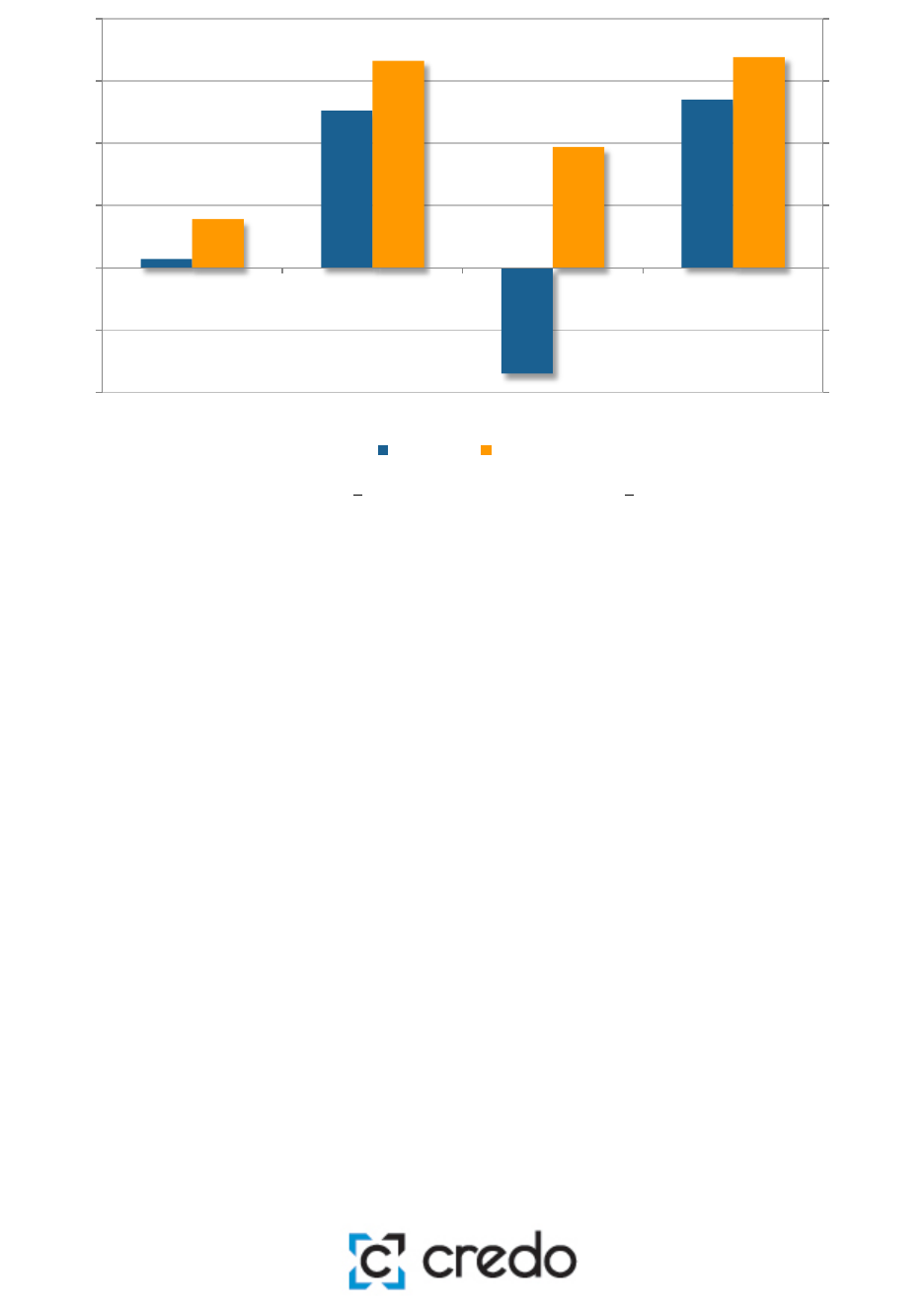

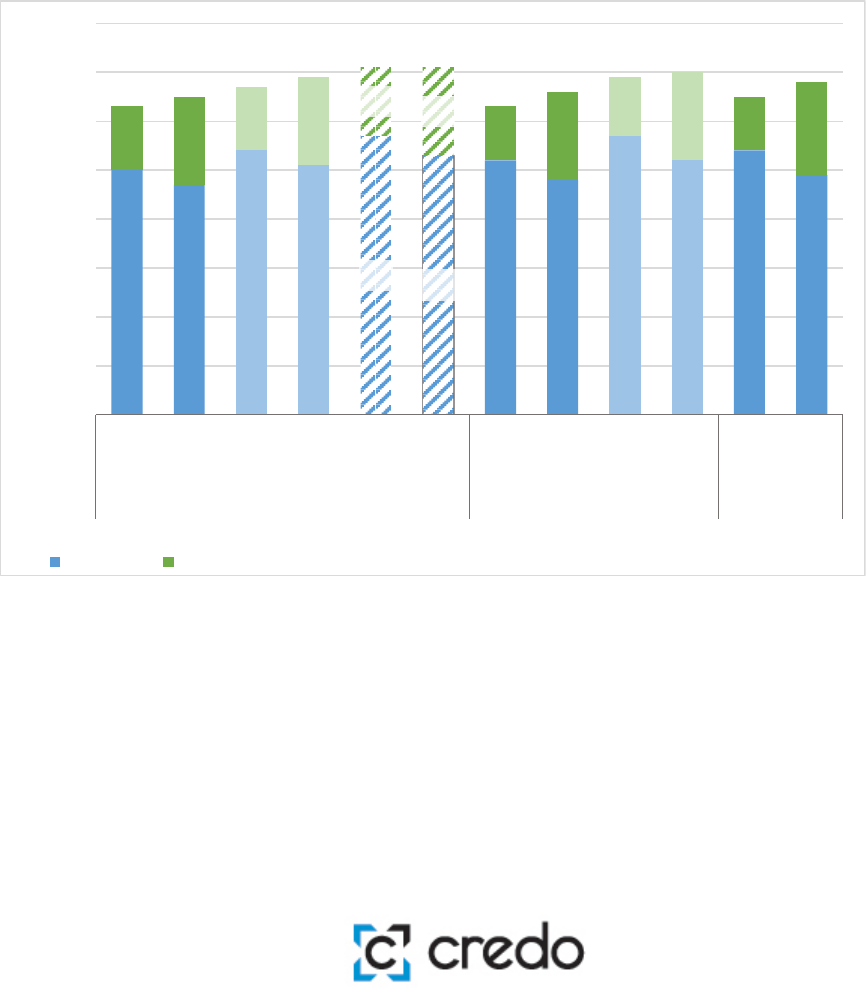

Charter School Impact by Students’ Years of Enrollment

Academic growth in charter schools may change depending on how many years a student is enrolled in

a charter school. In order to test this, we group students by the number of consecutive years they were

enrolled in charter schools. In this scenario, the analysis is limited to the charter students who enroll

for the first time in a charter school between the 2011-12 and 2014-15 school years. Although this

approach reduces the number of students included, it ensures an accurate measure of the years of

enrollment. For this reason, the results of this analysis contain a subset of the full study sample and

should not be directly compared with other findings in this report. This question examines whether the

academic success of students who enroll in a charter school changes as they continue their enrollment

in a charter school. The results are shown below in Figure 7.

Figure 7: Impact by Students’ Years of Enrollment

21

The results in Figure 7 above suggest that New York City charter school students in their first year in

charter school show a lower growth in reading compared to their TPS peers. During their first year of

charter enrollment, charter students experience about 63 days of learning gains in math. The second

year sees an increase in charter student growth, as charter students demonstrate 46 additional days

of learning in reading and 103 additional days of learning in math. The third year does not continue

this upward trend but remains positive and significant compared to the TPS comparison group for

both subjects. The learning gains for charter school students in their third year of enrollment translate

to 29 additional days of learning in reading and 86 days in math compared to TPS peers. Charter

school students in their fourth year of enrollment outperform their TPS virtual peers in both reading

and math. This translates to 68 days of additional learning in reading and 97 more days in math. Note

that due to the data window used in this study the number of charter school students enrolled for

three or four years is smaller than for one or two years, since only new students in the first years of the

study would be enrolled long enough to be included. The magnitude of impact and the level of

statistical significance is therefore worthy of note.

-.05**

.08**

.05**

.12**

.11**

.18**

.15**

.17**

-57

-28.5

0

28.5

57

85.5

114

-.10

-.05

.00

.05

.10

.15

.20

First Year Second Year Third Year Fourth Year

Days of Learning

Growth (in standard deviations)

* Significant at p < 0.05

** Significant at p < 0.01

Reading Math

22

Charter School Impact by Race/Ethnicity

Attention to achievement differences of students of various racial and ethnic backgrounds (also known

as student subgroups) has increased since the federal government’s passage of the No Child Left Behind

Act in 2001. The effectiveness of charter schools across ethnic and racial groups is especially important

given the proportion of charter schools focused on educating historically underserved students. The

impact of charter schools on the academic gains of Black and Hispanic students is presented in Figures

8 through 9a below.

The graphs display two distinct comparisons, described below:

1. The first comparison displays the growth of TPS students and charter students in the particular

subgroup of interest relative to the growth of the "average White TPS student," represented by

the 0.00 line on the graph. In this comparison, the White student is male and does not qualify

for subsidized school meals, special education services or English language learner support and

has not repeating his current grade. Both sets of bars reveal the difference in average

performance between the student in the subgroup of interest and the White TPS comparison

student. The stars indicate the level of statistical significance. Thus, if there are no stars, we

interpret the difference in learning gains as similar to the white TPS comparison because we

cannot determine if the observed differences are due to being a member of the subpopulation

or are due to chance. If there is no difference in the learning gains, the bar would be missing

entirely; if the learning of the student group in question is not as great as the comparison

baseline, the bar is negative; and if the learning gains exceed the comparison, the bar is

positive.

2. Graphs labeled “a” display the results of a second comparison testing whether the learning

gains in the charter school student subgroup differ significantly from their VCRs in the same

student subgroup. As with the first graph, stars denote statistical significance.

23

Figure 8: Learning Gains of Black Students Benchmarked Against Learning Gains of White TPS Students

As seen in Figure 8, in New York City, both Black charter schools students and Black TPS students have

significantly weaker academic growth in both reading and math when compared to the average White

TPS student. Black TPS students exhibit 114 fewer days of learning in reading and 137 fewer days of

learning in math. Black charter school students exhibit 91 fewer days of learning in reading and 80 fewer

days of learning in math compared to the average White TPS student. Figure 8a displays the differences

in learning between Black students enrolled in TPS and Black students enrolled charter schools.

-.20**

-.16**

-0.24**

-0.14*

-143

-114

-86

-57

-29

0

29

57

-.25

-.20

-.15

-.10

-.05

.00

.05

.10

Black Students in TPS Black Students in Charter

Days of Learning

Growth (in standard deviations)

* Significant at p < 0.05 ** Significant at p < 0.01

Reading Math

24

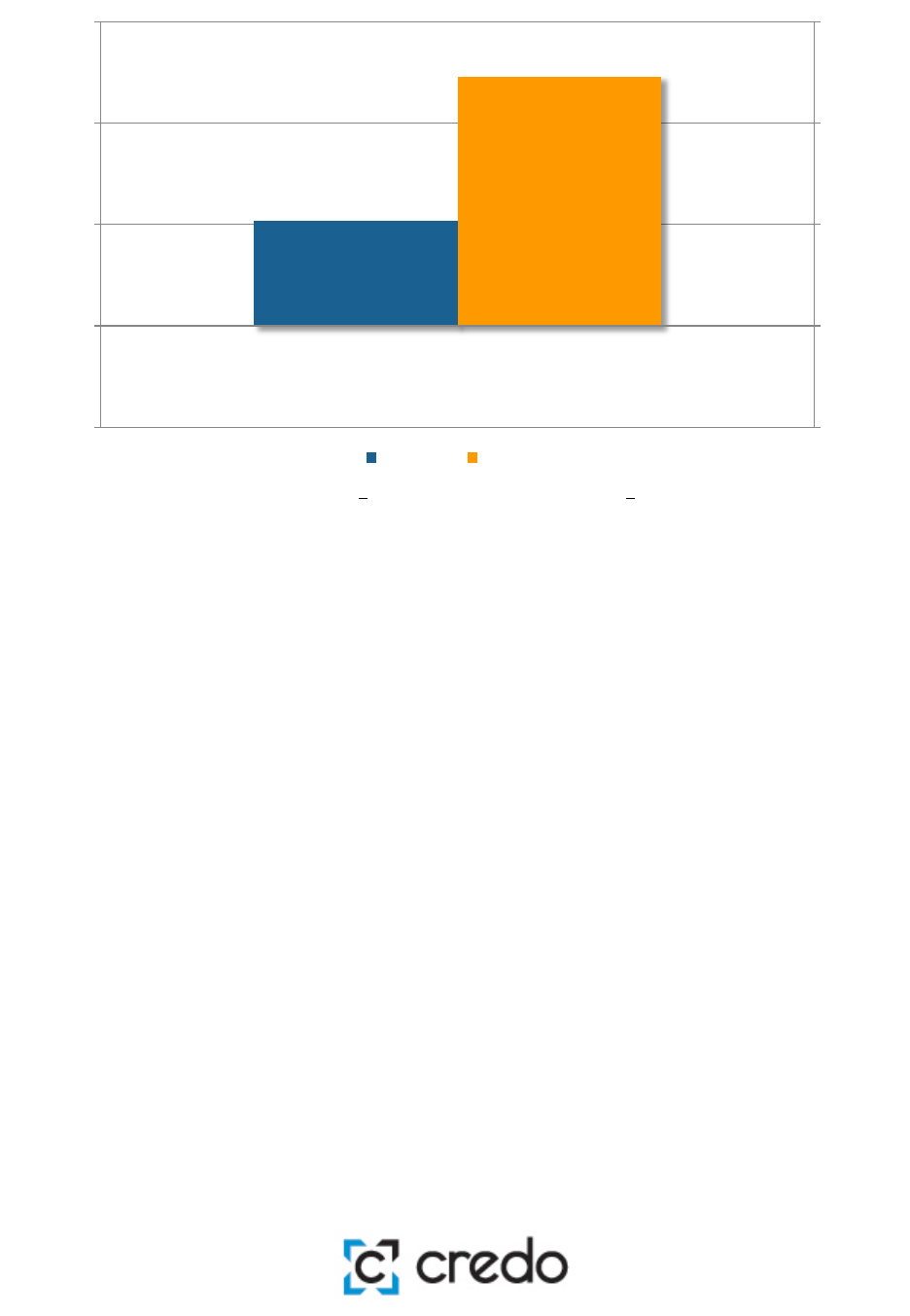

Figure 8a: Relative Learning Gains for Black Charter School Students Benchmarked Against their Black TPS

Peers

In New York City, Black charter students experience greater annual progress compared to their TPS

peers in both reading and math. The difference translates to 23 additional days of learning in reading

and 57 days in math. Since Black students account for roughly 56 percent of the charter school

population in this study, these findings explain a substantial portion of the overall performance of

charter schools in New York City.

.04**

.10**

-29

0

29

57

86

-.05

.00

.05

.10

.15

Days of Learning

Growth (in standard deviations)

* Significant at p < 0.05 ** Significant at p < 0.01

Reading Math

25

Figure 9

: Learning Gains of Hispanic Students Benchmarked Against Learning Gains of White TPS Students

In New York City, Hispanic students in both Charter schools and TPS have weaker learning gains in both

reading and math compared to the average White TPS student. Compared to White TPS students,

Hispanic TPS students experience 103 fewer days of learning in reading and 114 fewer days in math.

Hispanic students in charter schools experience 74 fewer days of learning in reading and 51 fewer days

of learning in math compared to White TPS students.

Figure 9a displays the relative differences in learning between Hispanic students enrolled in TPS and

Hispanic students enrolled in charter schools. In New York City overall, Hispanic students in charter

schools perform significantly better in both subjects than Hispanic students attending traditional

public schools. Hispanic charter students experience the equivalent of 29 and 57 more days of learning

in reading and math, respectively, when compared to Hispanic students attending TPS. These findings

have considerable weight in the overall performance of charter schools as a whole, as Hispanic students

make up more than 36 percent of this study’s charter school population.

-.18**

-.13**

-.20**

-.09**

-143

-114

-86

-57

-29

0

29

-.25

-.20

-.15

-.10

-.05

.00

.05

Hispanic Students in TPS Hispanic Students in Charter

Days of Learning

Growth (in standard deviations)

* Significant at p < 0.05 ** Significant at p

< 0.01

Reading Math

26

Figure 9a: Relative Learning Gains for Hispanic Charter School Students Benchmarked Against their Hispanic TPS

Peers

To briefly summarize, the race/ethnicity analyses in this report echo a familiar story: Black and

Hispanic students in both school settings perform worse than the average White TPS student in both

reading and math. Comparing the performance of the same student group across settings shows that

Black charter students outperform Black TPS students in reading and math. Similarly, Hispanic charter

students outperform Hispanic TPS students in both reading and math. Thus, for Black and Hispanic

students, the analysis indicates a significant academic advantage from charter school enrollment.

.05**

.10**

-29

0

29

57

86

-.05

.00

.05

.10

.15

Days of Learning

Growth (in standard deviations)

* Significant at p < 0.05 ** Significant at p < 0.01

Reading Math

27

Charter School Impact with Students in Poverty

Many charter operators expressly aim to improve educational outcomes for traditionally underserved

students, especially for students in poverty. CREDO’s 2013 National Charter Study found that students

in poverty comprise 53% of the national charter population

10

. In New York City, the proportion of

students in poverty is larger; 76 percent of charter students are eligible for subsidized school meals, a

proxy for low income households, as are 72 percent of TPS students. This makes the performance of

students in poverty even more germane in the local discussion of school quality.

Figure 10

: Learning Gains of Students in Poverty Benchmarked against Learning Gains of TPS Students not in

Poverty

Figure 10 above presents the academic growth for students in poverty. In this graph, the baseline is a

typical TPS student who is not eligible for free or reduced price school meals.

11

The performance of the

average non-poverty TPS student has been transformed to zero; the performance of poverty students

10

Cremata, Edward, D. Davis, K. Dickey, K. Lawyer, Y. Negassi, M. Raymond and J.Woodworth. National Charter

School Study 2013 (2013). https://credo.stanford.edu/documents/NCSS%202013%20Final%20Draft.pdf

11

Free and Reduced Price Lunch (FRL) is a standard indicator of poverty. Although we acknowledge that FRL is

not as sensitive as we desire, FRL is currently our best proxy for poverty.

-.03**

.01

-.03**

.10**

-86

-57

-29

0

29

57

86

-.15

-.10

-.05

.00

.05

.10

.15

TPS Students in Poverty Charter Students in Poverty

Days of Learning

Growth (in standard deviations)

* Significant at p < 0.05 ** Significant at p < 0.01

Reading Math

28

are displayed in relative terms. The analysis focuses on the relationship between poverty sector and

academic progress, holding all other factors constant. This leaves a picture of the difference in the

impact of charter attendance on students in poverty compared to similar students who are not in

poverty. The bars on the left hand side represent a TPS student in poverty, showing they perform

significantly lower than their non-poverty peers.

Charter students in poverty outperform their non-poverty peers in TPS in math and are on par in

reading. Both results are noteworthy. Not only are charter school students in poverty outpacing their

poverty peers in TPS to a significant degree in both reading and math, they also have progress that

closes the learning gap with their more affluent peers.

29

Charter School Impact with Race/Ethnicity and Poverty

The most academically needy students in public education are those who are both living in poverty and

a member of a racial or ethnic minority that has been historically underserved. These students face

multiple challenges, and their case has long been the focus of attention. Within the national charter

school community, this group receives special attention from many educators whose efforts are

specifically focused on addressing these students’ needs. The impact of New York City charter schools

on the academic gains of Black students living in poverty is presented in Figures 11 and 11a. Similarly,

Figures 12 and 12a present the impact of charter schools on Hispanic students living in poverty.

Figure 11

: Learning Gains of Black Students in Poverty Benchmarked against Learning Gains of White TPS

Students not in Poverty

In this analysis, the comparison TPS student is neither minority nor in poverty. As shown in Figure 11,

Black students living in poverty, regardless of whether they are enrolled in TPS or charters, make less

progress than the comparison TPS White students who are not in poverty. In New York City, Black TPS

students in poverty have approximately 148 fewer days of learning in reading and 171 fewer days of

learning in math than White non-poverty TPS students. Black charter students in poverty have 125

fewer days of learning in reading and 97 fewer in math than White non-poverty TPS students.

-.26**

-.22**

-.30**

-.17**

-200

-171

-143

-114

-86

-57

-29

0

29

-.35

-.30

-.25

-.20

-.15

-.10

-.05

.00

.05

Black TPS students in poverty Black Charter students in poverty

Days of Learning

Growth (in standard deviations)

* Significant at p < 0.05

** Significant at p

< 0.01

Reading

Math

30

Figure 11a: Relative Learning Gains for Black Charter School Students in Poverty Benchmarked Against their

Black TPS Peers in Poverty

Taking the results from the prior graph, we can evaluate the relative impact for Black students in

poverty across the two public school settings. Black charter students living in poverty learn significantly

more per year in both reading and math compared to Black TPS students living in poverty (Figure 11a),

amounting to 23 extra days in reading and 68 extra days of learning in math.

Across both school settings, Hispanic students living in poverty exhibit weaker performance in both

reading and math than non-poverty White TPS students. Figure 12 below shows that Hispanic TPS

students living in poverty experience on average 137 fewer days of learning in reading and 143 fewer

days in math compared to TPS White students who are not living in poverty. Hispanic students in

poverty attending charter schools have, on average, 108 fewer days of learning in reading and 74 fewer

days in math, per year compared to TPS White students not living poverty.

.04**

.12**

-29

0

29

57

86

-.05

.00

.05

.10

.15

Days of Learning

Growth (in standard deviations)

* Significant at p < 0.05 ** Significant at p < 0.01

Reading Math

31

Figure 12: Learning Gains of Hispanic Students in Poverty Benchmarked against Learning Gains of White TPS

Students not in Poverty

Figure 12a below shows the difference between Hispanic students living in poverty who attend charter

schools and Hispanic students living in poverty who attend TPS. In New York City, Hispanic charter

students in poverty experience 29 additional days of reading growth than Hispanic TPS students in

poverty. In math, Hispanic charter students exhibits stronger growth than Hispanic TPS students in

poverty, translating to approximately 68 more days of learning in math.

-.24**

-.19**

-.25**

-.13**

-171

-143

-114

-86

-57

-29

0

29

57

-.30

-.25

-.20

-.15

-.10

-.05

.00

.05

.10

Hispanic TPS students in poverty Hispanic Charter students in poverty

Days of Learning

Growth (in standard deviations)

* Significant at p < 0.05 ** Significant at p < 0.01

Reading Math

32

Figure 12a: Relative Learning Gains for Hispanic Charter School Students in Poverty Benchmarked Against their

Hispanic TPS Peers in Poverty

Adding the variable of poverty to the race/ethnicity analysis produces similar results to the earlier

race/ethnicity analysis. Being a member of a minority group and also in poverty leaves students even

further behind that either minority or poverty alone, showing the compounding effect for students.

Despite the additive effect of these challenges, charter school students have stronger academic gains

than their peers in TPS in both reading and math.

Charter School Impact with Special Education Students

Due to differences in individual needs, comparisons of outcomes of special education students are

difficult, regardless of where they enroll. In the ideal setting, we would restrict the comparison by

Individual Education Program (IEP) designation and only include students who were matched on each

demographic, including IEP designation. That approach however would result in fewer matches, so

pooling of special education students is needed to support a robust analysis. Because we cannot be

certain that the matches link students with similar needs, the forthcoming results should be interpreted

with caution. The demographic profiles in the current study reveal that 17 percent of the charter school

population in New York City has special education needs compared to 21 percent in TPS schools.

.05**

.12**

-29

0

29

57

86

-.05

.00

.05

.10

.15

Days of Learning

Growth (in standard deviations)

* Significant at p < 0.05 ** Significant at p < 0.01

Reading Math

33

Figure 13: Learning Gains of Special Education Students Benchmarked against Learning Gains of TPS Students

not in Special Education

New York City special education students enrolled in both TPS and charter schools have significantly

weaker growth than students in TPS who do not receive special education services. TPS students in

special education programs experience 103 fewer days of learning in reading and 108 fewer days of

learning in math when compared to TPS students not receiving special education services.

Interestingly, these differences are on par with the learning differences for Blacks and Hispanics. The

bars on the right side of Figure 13 show the impact of being a special education student in charter

schools. The results suggest that the full effect of being a special education student in a charter school

is less negative overall than being a special education student in TPS in both reading and math. The

difference between the two school settings is significant for both reading and math.

Charter School Impact with English Language Learners

There is a growing population of students entering the public school system with a primary language

other than English. Their present success in school will greatly influence their success in the world. The

2015 National Assessment of Education Progress (NAEP) documents the gap in performance between

English Language Learners (ELL) and their English proficient peers, with ELL students having weaker

-.18**

-.16**

-.19**

-.11**

-143

-114

-86

-57

-29

0

29

57

86

-.25

-.20

-.15

-.10

-.05

.00

.05

.10

.15

TPS Students in Special Education Charter Students in Special Education

Days of Learning

Growth (in standard deviations)

* Significant at p < 0.05 ** Significant at p < 0.01

Reading Math

34

performance

12

. Our analysis, in both reading and math, align with NAEP results. As shown in Figure 14,

English language learners in TPS schools show significantly weaker growth per year than non-ELL

students, amounting to a gap of 51 days of learning in reading and 38 less days in math.

In Figure 14, the pair of bars on the right represent the average difference between being a charter

student with ELL designation a non-ELL TPS student. Charter students with ELL designation experience

57 fewer days of learning in reading and similar learning in math to their non-ELL TPS counterparts.

When compared to the same baseline, charter ELL students experienced similar growth in reading as

TPS ELL students, the blue bars are similar in size. The difference is not statistically significant.

However, in math charter ELL students have stronger growth than TPS ELL students, and even are on

par with students with no language limitations. The statistically significant difference that math charter

ELL students have compared to the TPS ELL students amounts to roughly 40 more days of growth for

ELL students attending a charter school.

Figure 14: Learning Gains of ELL Students Benchmarked Against Learning Gains of Non-ELL TPS Students

12

The Nation’s Report Card. (2016) 2015 Mathematics and Reading Assessments

http://www.nationsreportcard.gov/reading_math_2015/#mathematics/groups?grade=4

-.09**

-.10**

-.07**

.00

-171

-143

-114

-86

-57

-29

0

29

57

86

-.25

-.20

-.15

-.10

-.05

.00

.05

.10

.15

TPS Students with ELL designation Charter Students with ELL designation

Days of Learning

Growth (in standard deviations)

* Significant at p < 0.05 ** Significant at p < 0.01

Reading Math

35

36

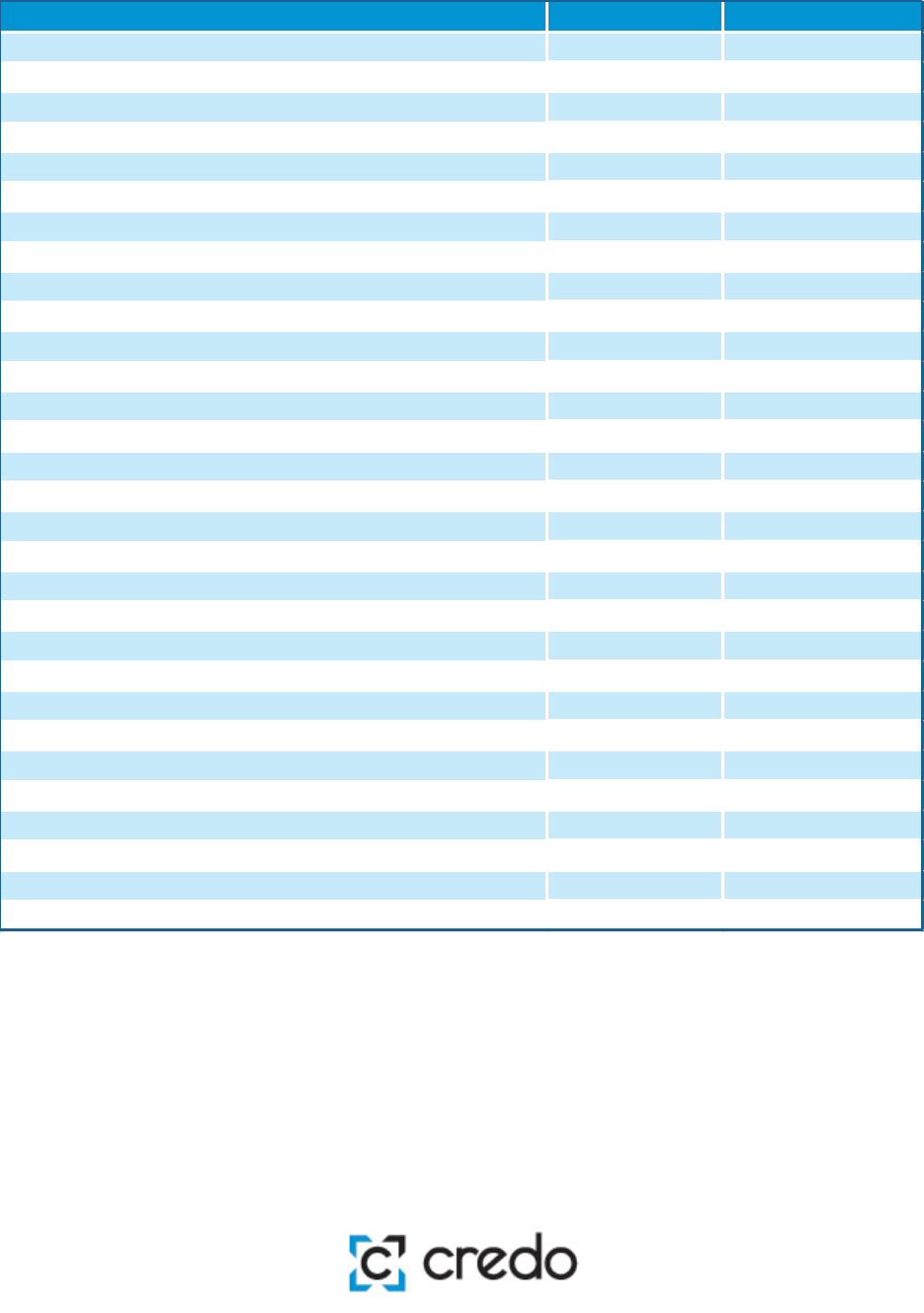

School–level Analysis

In the preceding sections the analyses have highlighted the performance of charter school students in

New York City including the breakdown of subgroups analysis. However, in addition to that, education

policy makers would like to know the school-level academic performances. Similarly, parents and the

public at large want to make informed enrollment decisions based on the schools’ progress in their

communities.

Comparing School-level Quality In order to determine the current distribution of charter school

performance, the average effect of charter schools on student learning over the two most recent growth

periods (2015 and 2016) is compared to the experience that students would have realized in their local

traditional public schools.

13

The educational market consists of VCR students matched with each

student in a given charter school. This analysis provides an average contribution to student learning

gains for each charter school. This measure is called the school’s “effect size”. As with the overall and

by-year impacts, school effect size is expressed in standard deviations of growth.

As noted in Table 1, charter schools are smaller on average than their corresponding feeder schools.

Further, some charter schools elect to open with a single grade and mature one grade at a time.

Consequently, care is needed when making school-level comparisons to ensure that the number of

tested students in a school is sufficient to provide a fair representation of the school’s impact. Our

criteria for inclusion were at least 60 matched charter student records over the two years or at least 30

matched charter records for new schools with only one year of data. Our total sample consists of 144

schools with reading scores and 153 schools with math scores in the 2015 and 2016 growth periods.

Table 4 below shows the breakout of performance for the New York City charter schools that meet our

criteria for inclusion by having a sufficient number of charter student records.

Table 4: Performance of Charter Schools Compared to Their Local Schools in New York City

13

We chose to include only the two most recent growth periods in this analysis because we wanted a highly

relevant contemporary distribution of charter school performance.

Subject Number Percent Number Percent Number Percent

Reading 23 16.0% 59 41.0% 62 43.1%

Math 26 17.0% 54 35.3% 73 47.7%

Significantly

Worse

Not Significant

Significantly Better

37

In reading, 43 percent of charter

schools perform significantly better

than their peer traditional public

schools, while nearly 48 percent

perform significantly better in math.

Each of these results show growth

larger than the national average

(nationally, 25 percent of charter

schools outperform their local

counterparts in reading and 29 percent

do so in math

14

). When looking at

weaker performance, 16 percent of

New York City charter schools have

reading results that are significantly

weaker than the local TPS option,

while 17 percent do so in math

(nationally, 19 percent of charter

schools perform lower than the local

counterparts in reading and 31 percent

do so in math). In reading, 41 percent

of charter schools do not differ

significantly from traditional public

schools in their communities. In math,

35 percent of charter schools have

growth performance that is indistinguishable from TPS in New York City.

Impact of Growth on Achievement While the impacts of charter schools on academic growth relative

to their local competitors is informative, these analyses do not indicate how well students perform in

absolute terms. Since many of the students served by charter schools start at low levels of achievement,

their absolute achievement (in addition to their relative growth) is vital to understanding student

success overall. To do this, each school’s average growth is placed in the context of their school wide

achievement level compared to the rest of the state, as in Tables 5 and 6 below. We use the effect sizes

discussed above to measure growth. The school’s average achievement level is the mean achievement

of the students over the same two periods covered by the effect size analysis (2015 and 2016).

15

The 50

th

percentile indicates statewide average performance for all public school students (traditional and

charter). A school achievement level above the 50

th

percentile indicates that the school's overall

achievement exceeds the statewide average.

14

CREDO (2013). National Charter School Study 2013. http://credo.stanford.edu.

15

Average achievement was computed using students’ z-scores from the end of the growth period (e.g., spring

2014 and spring 2015), and the resulting school-level mean was then converted into a percentile.

A Note about

Tables 5 and 6

There are four quadrants in each table. We have expanded on

the usual quadrant analysis by dividing each quadrant into

four sections. The value in each box is the percentage of

charter schools with the corresponding combination of growth

and achievement. These percentages are generated from the

2015 and 2016 periods.

The uppermost box on the left denotes the percentage of

charters with very low average growth but very high average

achievement. The box in the bottom left corner is for low-

growth, low-achieving schools.

Similarly, the topmost box on the right contains the

percentage of charters with very high average growth and very

high average achievement, while the bottom right corner

contains high-growth, low-achieving schools.

The major quadrants were delineated using national charter

school data. We would expect the majority of schools to have

an effect size between -0.15 and 0.15 standard deviations of

growth (the two middle columns). Similarly, we would expect

about 40% of schools to achieve between the 30

th

and 70

th

percentiles.

38

Table 5: Reading Growth and Achievement

In reading, 88 of the 144 New York City charter schools (61 percent) have positive average growth (this

percentage is the sum of the eight squares in the blue and pink quadrants in the right half of the table).

Thirty nine percent of charters have positive growth and average achievement above the 50

th

percentile

of the state (i.e., the total for the blue quadrant on the top right). Nearly 39 percent of schools post

smaller learning gains than their local peer schools (the sum of gray and brown quadrants on the left

half of the table). About 48 percent of charters perform below the 50

th

percentile of achievement (the

sum of the brown and purple cells in the lower portion of the table). The area of greatest concern is the

26 percent of schools that fall into the lower left quadrant of the table. These schools are characterized

by both low achievement and low growth.

Growth

(in Standard

Deviations)

0.0% 0.7% 1.4% 7.6%

70th Percentile

0.0% 12.5% 18.8% 11.1%

50th Percentile

1.4% 20.1% 18.8% 3.5%

30th Percentile

2.1% 2.1% 0.0% 0.0%

-0.15

0.15

Low Growth,

High Achievement

High Growth,

High Achievement

Low Growth,

Low Achievement

High Growth,

Low Achievement

0

39

Table 6: Math Growth and Achievement

In math, 107 of the 153 New York City charter schools (nearly 70 percent) have positive average growth

in math, as seen in the combined orange and pink quadrants in the right half of the table. Approximately

47 percent of charters have positive growth and average achievement above the 50

th

percentile (the

orange quadrant in the upper right of the table). Approximately 46 percent of charters post

achievement results below the 50

th

percentile of the state for math (the sum of cells in the lower half of

the table); these findings are similar to those presented in Table 5 for reading. In the pink quadrant in

the lower right of the table, 24 percent (36 schools) of the 153 schools classified as having low

achievement have high growth and appear to be on an upward trajectory. As in the previous table, the

schools of greatest concern are those schools in the lower left (brown) quadrant that have both low

achievement and low growth; they account for 23 percent (35 schools) of the charter schools in New

York City.

Growth

(in Standard

Deviations)

0.0% 0.0% 3.9% 9.2%

70th Percentile

0.0% 7.2% 14.4% 19.0%

50th Percentile

1.3% 13.1% 17.0% 6.5%

30th Percentile

7.2% 1.3% 0.0%

0.0%

-0.15

0.15

Low Growth,

High Achievement

High Growth,

High Achievement

Low Growth,

Low Achievement

High Growth,

Low Achievement

0

40

Impact of Charter Management Organizations

Charter Management Organizations (CMOs) are entities that operate multiple schools, sharing common

leadership and practices. We define CMOs by using two criteria: first, CMOs are organizations operating

three or more schools. Second CMOs hold the charters for the schools they operate.

16

CMOs have some

operational advantages in their ability to spread administrative fixed costs over a larger number of

schools or students, thus providing the possibility of greater efficiency (i.e. the cost per student or per

school is lower). In addition, with more schools and students than a single charter school, CMOs may

be able to support additional programs and more robust staffing in their networks. Whether these

organizations lead to better student outcomes is a matter of interest across the United States.

Identifying all the CMOs in New York City and associating them with their schools and students is not

straightforward. This analysis only includes schools located in New York City, even if a CMO also

operates schools in other communities. The CMO analysis includes 66 charter schools from 13 CMOs.

The analysis looks at the comparative performance of charter schools that belong to charter

management organizations (CMOs) and those that do not belong to CMOs. As with the earlier statewide

graphs, each graph in this section displays two distinct comparisons:

1. The first graph compares the performance of charter students enrolled in CMO-affiliated

schools and charter students in independent charter schools to the performance of the

"average statewide student in TPS."

2. The second graph compares the difference in learning between charter students who attend

CMO charter schools and those who attend charters that are not part of CMOs.

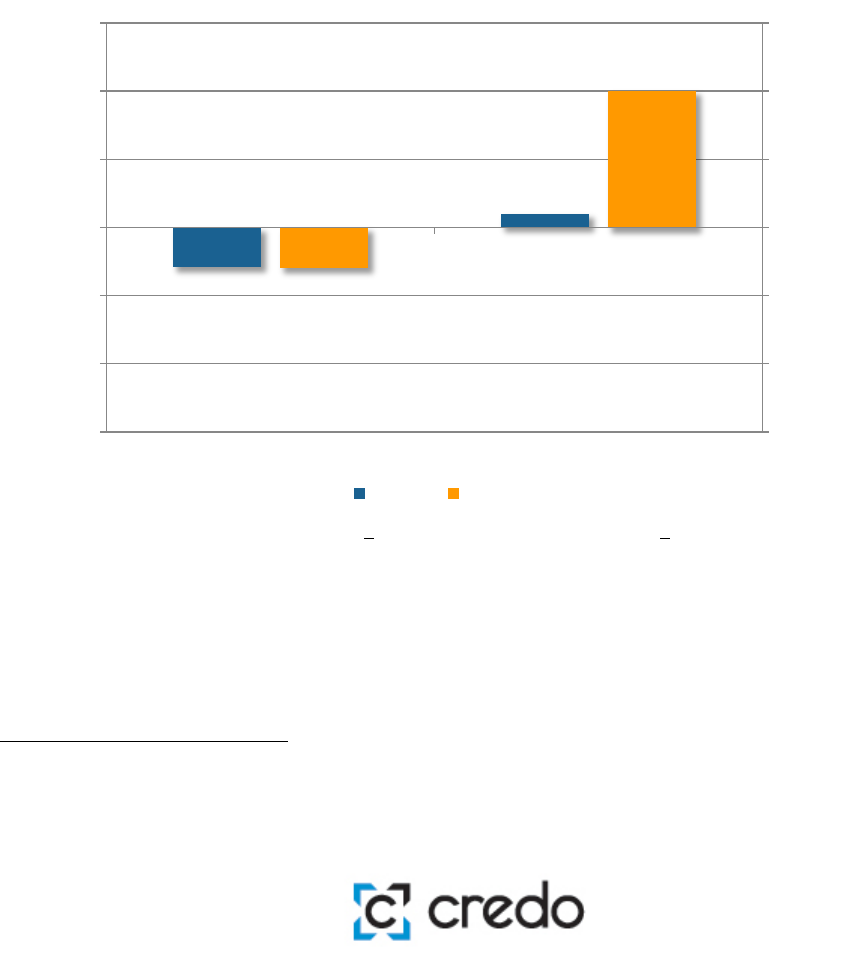

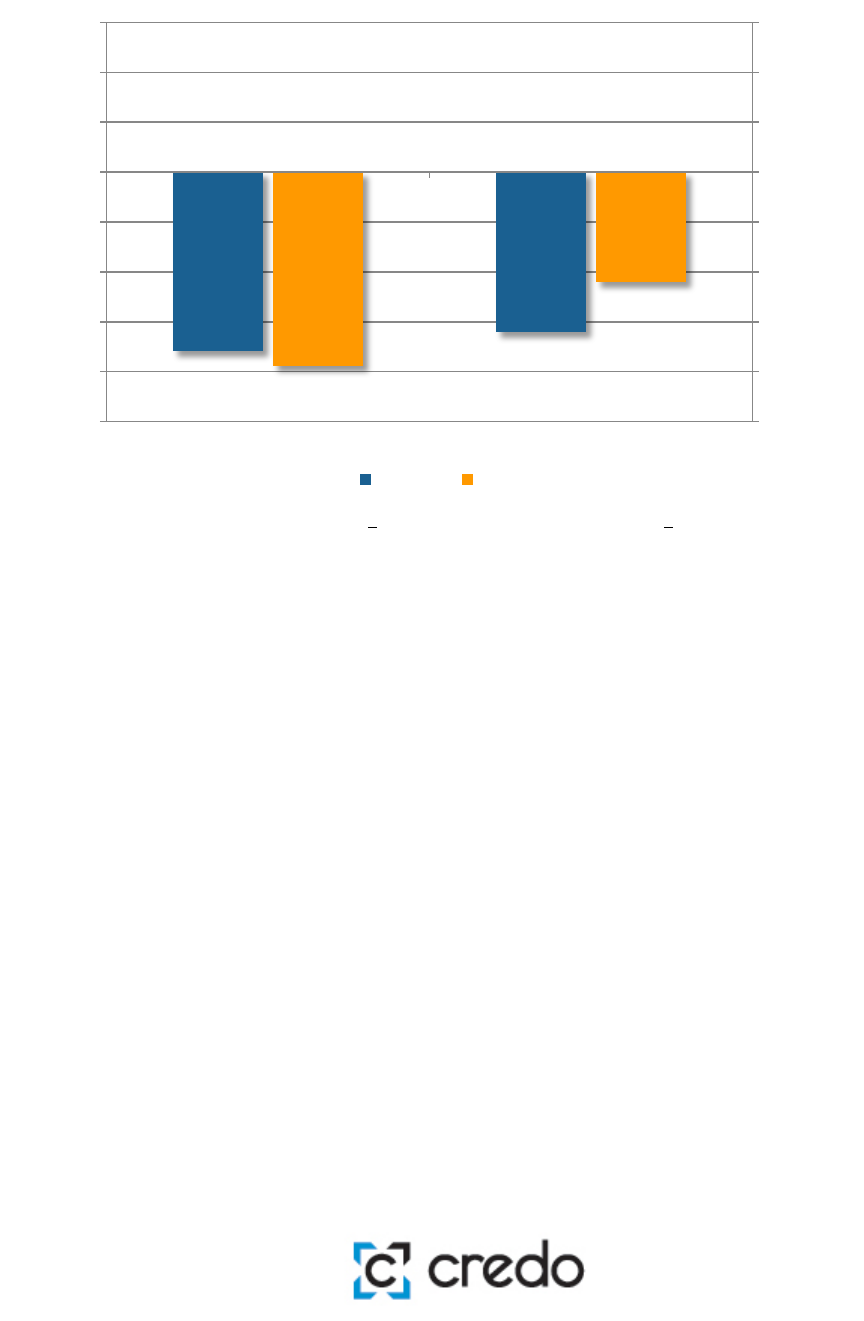

Figure 15 illustrates the impact of CMO charter schools and non-CMO charter schools on their students’

math and reading growth. This growth is benchmarked against growth of an average White TPS

student.

16

The New York State Charter Schools act prohibits for-profit firms from applying for a charter.

41

Figure 15: Average Student Learning Gains of CMO Charter Schools and Non-CMO Charter Schools Benchmarked

Against the Statewide Average TPS Student Learning Gains

In both reading and math, New York City students enrolled in a CMO charter exhibit stronger average

growth compared to their TPS peers: they get approximately 46 more days of learning in reading and

97 more days in math. The graph also shows that students enrolled in a charter that is not part of a CMO

perform similarly to their TPS peers in reading but experience 34 days of additional learning in math.

Figure 15a displays the learning difference between students who attend CMO charters and those who

attend non-CMO charters. The figure shows that CMO charter students exhibit stronger growth

translating to approximately 40 more days of learning in reading and 63 more days in math compared

to non-CMO charter students.

.08**

.00

.17**

.06**

-29

0

29

57

86

114

-.05

.00

.05

.10

.15

.20

Charter CMO Charter Non-CMO

Days of Learning

Growth (in standard deviations)

* Significant at p < 0.05 ** Significant at p < 0.01

Reading Math

42

Figure 15a: Relative Student Learning Gains of CMO Charter Schools Benchmarked Against Learning Gains of

Non-CMO Charter Schools

In order to better understand the performance of charter schools associated with CMOs and

independent charter schools, schools were grouped by grade span. Figure 16 shows that charter

elementary school students, both CMO and non-CMO, perform better than students in TPS elementary

schools in both reading and math. CMO elementary students outperform their TPS peers with an

additional 29 days of learning in reading and 74 additional days in math.

In middle school, students enrolled in CMO charters outperform their TPS peers in both reading and

math. The largest gains for middle school CMO charter students across all grade spans are represented

by an additional 125 days of learning in math. Students enrolled in non-CMO charter middle schools

performed similarly to their TPS counterparts in both reading and math. High school students enrolled

in CMO charters experience similar growth to their TPS counterparts in reading but gained 63 additional

days of learning in math. The students in non-CMO charter high schools perform similarly to their TPS

counterparts in both math and reading. The results for students in CMO charter multi-level schools were

dramatic: they exhibit a learning gain of 57 days in reading and 114 days in math compared to their

TPS peers. Students enrolled in multi-level independent charter schools exhibit similar growth to their

TPS peers in both subjects.

.07**

.11**

-57

-29

0

29

57

86

-.10

-.05

.00

.05

.10

.15

Days of Learning

Growth (in standard deviations)

* Significant at p < 0.05 ** Significant at p < 0.01

Reading Math

43

Figure 16: CMO and Non-CMO Student Learning Gains by School Level Benchmarked Against TPS Learning Gains

by School Level

Figure 16a below shows how the two types of charter schools compare to each other; these results