Petra Sleeman* and Tabea Ihsane

Convergence and divergence

in the expression of partitivity

in French, Dutch, and German

https://doi.org/10.1515/ling-2020-0090

Abstract: This paper focusses on the so-c alle d partitive pronou n in French

and Dutch, and the corresponding data in German, a language which is

assumed not to have partitive pronouns in its standard, in contrast to certain

dialectal varieties. Taking the diverse uses of the French partitive pronoun en

as a starting point, we investigate the corre sponding constructions in Dutch

and German. The ultimate aim of the paper is to develop an analysis

accounting for the similarities and differences between these languages in

relation to the presence/absence of the partitive pronoun. To reach our

objectives, we rely on data collected in a G rammaticality Judgment Test

taken by native speakers of French, Dutch and Germ an. We put together

theory and experi men tal data i n a crossl ingui stic p ersp ective i nvestig ating

three languages that differ in their uses of partitive elements and f ormalize

the results in a model in which the partitive pronoun can replace different

portions of the nominal structure.

Keywords: partitivity, (non-)referentiality, DP-structure, partitive pronoun

1 Introduction

In French, partitivity, i. e., the relation between a part and a whole/set, can be

expressed in various ways: by proper partitive constructions as in (1), by parti-

tive articles as in (2), and by the partitive pronoun en.

1

*Corresponding author: Petra Sleeman, Department of Linguistics, University of Amsterdam,

Tabea Ihsane, Département de linguistique, Université de Genève, Rue de Candolle, Genève

1 We are using the term “partitive article” for the morphological elements du, de la, de l’, des

and are conscious that in partitive examples like (2) du is not an article but the combination of

the preposition de ‘of’ and the definite article le ‘the’, as observed by a reviewer. The term

partitive article is therefore a misnomer (not mentioning the fact that nominals introduced with

this element are often indefinite and not partitive in meaning; cf. Delfitto and Schroten 1991,

Linguistics 2020; 58(3): 767–804

Open Access. © 2020 Sleeman and Ihsane, published by De Gruyter. This work is licensed

under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 License.

(1) a. J’ai bu un verre de ce jus.

‘I have drunk a glass of this juice.’

b. J’ai lu deux de tes livres.

‘I have read two of your books.’

(2)

J’ai bu du lait (qui était dans le frigo).

I have drunk of.the milk that was in the fridge

‘I drank from the milk that was in the fridge.’

(3)

[Situation: I have bought five apples.]

J’ en ai mangé deux immédiatement.

I

EN

have eaten two immediately

‘I immediately ate two of them.’

In this paper, we focus on examples with the pronoun en ‘of.them’,asin(3),but

also on examples like (4), which contains a partitive pronoun but which is

quantitative in interpretation, in the sense that there is no whole/set implied, in

contrast to (3).

(4) Combien de frères a-t-elle ? Elle en a trois.

how.many of brothers has she she

EN

has three

‘How many brothers does she have? She has three.’

As the above examples show, the term partitive pronoun for elements like en is a

misnomer. However, in the absence of a better alternative, we will use that term

for presentational reasons. By extension, partitivity may refer to contexts/expres-

sions with a partitive pronoun, although the notion can also be used in a

broader sense, covering, e. g., also examples such as (1)-(2). The use of the

French pronoun en, which is a clitic, has been extensively studied, both from

a descriptive and a theoretical point of view (Milner 1976; Pollock 1998; Ihsane

2013). Ihsane (2013) claims that en can replace different portions of the noun

phrase. In (3) en pronominalizes a smaller portion of the DP than in (5), which

does not contain a quantifier:

among others; see also https://www.uzh.ch/spur/blog/on-the-so-called-partitive-article-in-

french/).

768 Petra Sleeman and Tabea Ihsane

(5) Paul cherche des noisettes. Il en cherche.

Paul is.looking.for of.the nuts he

EN

is.looking.for

‘Paul is looking for (some) nuts. He is looking for some.’

According to Ihsane (2013), en replaces the complement of the numeral in (3),

whereas it pronominalizes the whole complement des noisettes ‘(some) nuts’ in

(5). The author models the conditions of the use of partitive en in a DP structure

in which various uses of en correspond to different portions of the DP, headed

by different functional projections.

In Dutch, the standard use of the partitive pronoun er, which is also called

quantitative pronoun, is its combination with a quantified indefinite noun

phrase in object position, like the French (4)

2

:

(6) Hoeveel broers heeft ze? Ze heeft er drie.

how.many brothers has she she has

ER

three

‘How many brothers does she have? She has three.’

De Schutter (1992) observes that in some Dutch dialects, especially in Belgium,

but not in standard Dutch, er can replace the whole indefinite noun phrase, just

like French en in (5)

3

:

(7) Ik koop wel eens postzegels, maar ik verkoop er

I buy sometimes stamps but I sell

ER

nooit. (dialectal Dutch)

never

‘Sometimes I buy stamps, but I never sell any.’

In contrast to some German dialects, standard German does not possess a

partitive pronoun like en/er. However, Strobel (2016) shows that standard

2 There exist other types of er in Dutch (cf. Bennis 1986, who identifies four types), like the

locative pronoun in (i) (cf. Section 5), from Veenstra et al. (2010):

(i) Hij heeft er het boek gekocht.

he has

ER

the book bought

‘He has bought the book there.’

For a theoretical analysis of the partitive/quantitative pronoun Barbiers (2005, 2017) and Corver

et al. (2009), among others.

3 For a theoretical analysis of the use of er in Dutch dialects, see, among others,. Kranendonk

(2010).

Convergence and divergence 769

German uses the pronominalized adjectival pronoun welch- (which can also be

used as an interrogative pronoun: welche Frau ‘which woman’) to express an

undefined quantity

4

:

(8) A: Ich hätte gerne Radieschen. Hast du welche da?

‘I would like (some) radishes. Do you have any?’

B: Ja, da sind welche. Warte, ich geb dir welche.

‘Yes, there are some. Wait, I’ll give you some.’

(Strobel 2016)

Welch- is one of the four strategies of partitive-anaphoric reference in the

German language (Glaser 1993).

5

In this paper, we only discuss this strategy,

as it is the one found in contemporary Standard German.

To our knowledge, a relation between French en or Dutch er and the

expression of partitivity in German has never been made explicit or investigated

in the linguistic literature. One of the goals of this paper is to fill this gap. The

perspective is therefore crosslinguistic, but, because of the richness and the

variation in the use of the French pronoun en, we will take the limitations and

possibilities of this pronoun as our starting point. What we want to know is how

the ways in which en is used in French are expressed i) in languages that also

possess a partitive pronoun like en/er, and ii) in languages that do not possess

such a partitive pronoun. For the first type of languages we study Dutch, and for

the second type of languages we take German as a representative, although this

does not necessarily mean that other languages behave exactly in the same way.

More generally, this paper will contribute to the understanding of the expression

of partitivity in Dutch and German, about which relatively little is known, in

contrast to French.

Our methodology consists in using and analyzing equivalent Grammaticality

Judgment Tasks submitted to native speakers of French, Dutch and German. We

will model our results for Dutch and German in DP structures comparable to the

one proposed for French by Ihsane (2013). This will enable us to compare the

expression of partitivity in the three languages in a proper way.

This paper is structured as follows. In Section 2, we unfold the subtleties of

the use of the partitive pronoun in French, and we present Ihsane’s(2013)

4 Low/Northern German also use this pronoun, which is spreading into different dialects of

German as an alternative to the partitive forms (d)(ǝ)r(ǝ/u) (Strobel 2013).

5 The other strategies are: genitive pronouns, null anaphora, and the indefinite pronoun ein (cf.

also Strobel 2013).

770 Petra Sleeman and Tabea Ihsane

theoretical modelling that accounts for the various possibilities of its use. In

Section 3, we present our methodology and in Section 4 the results of the

Grammaticality Judgment Tasks that we submitted to native speakers of French,

Dutch and German. Our results are discussed in Section 5 and modelled in DP

structures comparable to the one proposed by Ihsane (2013) for French in Section

6. In Section 7, we summarize our findings and make some suggestions for future

research.

2 The use and syntactic analysis of the partitive

pronoun in French

2.1 The use of en

Although we call en in the present paper a partitive pronoun, it is also called a

quantitative pronoun in the literature, just like Dutch er. Milner (1978) makes a

distinction between the quantitative and the partitive pronoun en. While (9a)

illustrates the partitive use of en, like (3), (9b) illustrates the quantitative use,

like (4). In addition, en occurs in genitive constructions as illustrated in (10)

(Milner 1978), which will not be discussed in this paper:

(9) [Situation: Yesterday five students came to see me.]

a. Aujourd’hui j’ en ai revu deux (de ces étudiants) . Partitive

today I

EN

have seen.again two (of these students)

‘Today I saw again two of them.’

b. Aujourd’hui j’ en ai aussi vu cinq (d’ étudiants). Quantit./Indef.

today I

EN

have also seen five (of students)

‘Today, I also saw five.’

(10)

a.

Jean se souvient de toutes ses erreurs. Genitive

Jean

REFL

remembers of all his mistakes

‘Jean remembers all his mistakes.’

b. Jean s’ en souvient .

Jean

REFL EN

remembers

‘Jean remembers them.’

In (9a), en has a partitive interpretation, as the two students (sub-set) are part of

the five students (set) mentioned in the context. In (9b), in contrast, en is

Convergence and divergence 771

indefinite/quantitative as it is about five different, not yet mentioned, students.

Such uses are often referred to as quantitative, as they involve a quantifier such

as a numeral (cinq ‘five’ in (9b)). In (10), en replaces the prepositional phrase de

toutes ses erreurs ‘of all his mistakes’ selected by the verb se souvenir ‘remem-

ber’, which takes a complement introduced by the preposition de ‘of’.

In standard French, the use of en is compulsory with an indefinite noun

phrase introduced by a quantifier in object position. In (9a) and (9b) this is a

cardinal number, but it may also be another type of quantifier:

(11) Je visiterai quelques musées. J’ *(en) visiterai quelques-uns.

6

I will.visit some museums I

EN

will.visit some

‘I will visit some museums. I will visit some.’

Furthermore, en is also used in combination with an elliptical noun phrase

containing an adjective:

(12) Marie a acheté un ballon bleu. Pierre en a acheté un rouge.

Marie has bought a ball blue Pierre

EN

has bought a red

‘Marie has bought a blue ball. Pierre has bought a red one.’

Since en can only be combined with indefinite noun phrases, the use of en with

a definite elliptical noun phrase containing an adjective yields an ungrammat-

ical result:

(13) Tristan a vu le petit hôtel. Paul (*en)a vu le grand.

Tristan has seen the small hotel Paul

EN

has seen the big

‘Tristan has seen the small hotel. Paul has seen the big one.’

As seen in the introduction, en can also replace some complements with a

partitive article, as in (5), repeated below for convenience:

(14) Paul cherche des noisettes. Il en cherche.

Paul is.looking.for of.the nuts he

EN

is.looking.for

‘Paul is looking for (some) nuts. He is looking for some.’

Such examples can be classified into the indefinite/quantitative type, even

though there is no quantity expressed overtly. Like other indefinite noun phrases

(e. g., with the indefinite article un(e); cf. Fodor and Sag 1982), des-complements

6 Quelques-uns is the pronoun corresponding to quelques when the latter is not directly

followed by a noun.

772 Petra Sleeman and Tabea Ihsane

can be referential or not (Ihsane 2008). In (14), des noisettes is not referential, in

contrast to des enfants in (15):

(15) [Situation: You point at Paul and Marie and you say]:

Je vois des enfants sur la plage. Tu (*en)/ les vois aussi ?

I see of.the children on the beach you

EN

/ them see too

‘I see children on the beach. Do you also see children/them?’

In (15), the pronoun les refers back to des enfants, which identifies the children

as Paul and Marie. The pronoun en cannot have this function, hence the

association of en with non-referentiality. En is indeed an anaphoric pronoun

which does not involve co-reference with its antecedent (Milner 1978; Lamiroy

1991; Corblin 1995). The fact that en is required in (14) but excluded in (15) shows

that there is no perfect correspondence between partitive articles and the parti-

tive pronoun in French: some nominal phrases with a partitive article can be

replaced by en, whereas others cannot.

Other constructions of which Ihsane (2013) claims that they can only be non-

referential are negated mass and negated plural indefinites. These can therefore

only be replaced by en and not by les:

(16) Anne: Tu ne bois jamais de vin?

you NEG drink never of wine

Lucie: Non, je n’ en /*le bois jamais.

no I

NEG EN

/ it drink never

‘Anne: Do you never drink wine? Lucie: No, I never drink wine.’

(17)

Pierre: Tu n’ as pas pris de médicaments aujourd’hui?

you NEG have

NEG

taken of medicines today

‘Didn’t you take any medicines today?’

Fred: Non, je n’ en ai pas pris/ *je ne les ai pas

no I

NEG EN

have

NEG

taken/ I

NEG

them have

NEG

pris.

taken

‘No, I did not take any.’

With non-negated mass nouns, too, en is required and the definite pronoun

excluded:

(18) Louis : Les chats ont bu du lait ce matin ?

the cats have drunk of.the milk this morning

Convergence and divergence 773

Jeanne: Oui, ils *(en) /*l’ ont bu.

yes they

EN

/ it have drunk

‘Louis: Did the cats drink milk this morning? Jeanne: Yes, they drank

some.’

The various uses of en described in this section have been claimed to be

pronominalizations of different portions of the DP structure, as we show in the

next subsection.

2.2 Syntactic analysis

In her work on en, Ihsane (2013) assumes that this pronoun replaces various

constituents headed by de: in genitive and partitive examples like (10) and (9a),

en replaces a prepositional phrase headed by the preposition de (19a)–(19b). In

indefinite constructions introduced by a partitive article, en replaces the whole

noun phrase, including the partitive determiner (19c). In the quantitative con-

struction and the negated NPs, it replaces a portion of the nominal structure

containing a functional element de (19d)–(19e).

7

Examples (19a)–(19d) have been

slightly adapted from Hendrick (1985: 178), who does not address constituents

with du, for instance:

(19) a. Genitive phrase le début de ton livre → [de ton livre] = en

the beginning of your book

b. Partitive phrase beaucoup de tes livres → [de tes livres] = en

a.lot of your books

c. du/des NP du/des N → [du/des N] = en

of.the N

d. Quantified NP beaucoup de N → [de N] = en

a.lot of N

e. Negated NP pas de N → [de N] = en

not of N

In the previous section, we showed that Ihsane (2013) makes a distinction

between two types of des-phrases (19c): referential ones (15) and non-referential

ones (14).

7 That de in quantitative examples (e. g., beaucoup de livres ‘a lot of books’) is not a preposi-

tion, in contrast with de in partitive and genitive constructions, is well-known (Milner 1978;

among others). For a different analysis of de in partitive constructions see Kupferman (2001)

and Carlier and Melis (2006).

774 Petra Sleeman and Tabea Ihsane

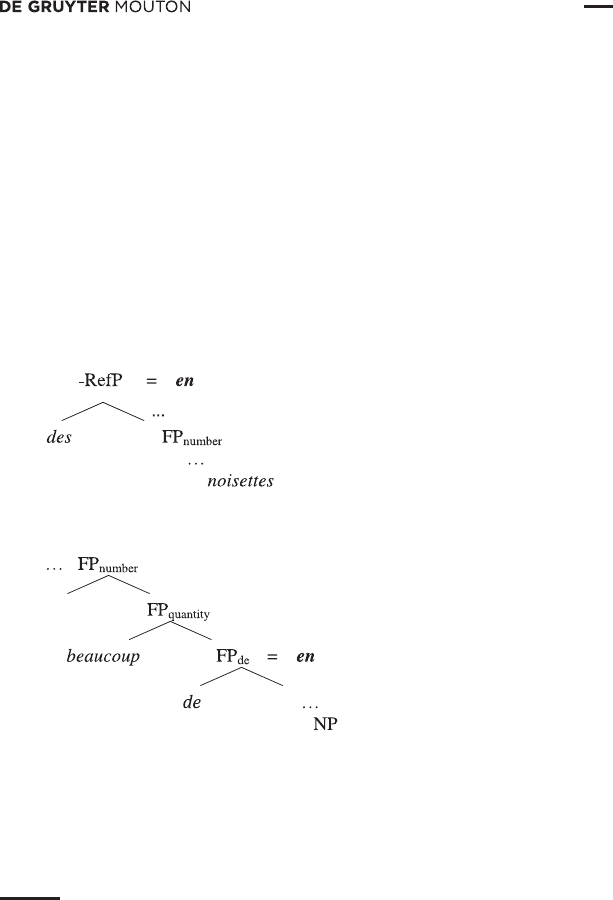

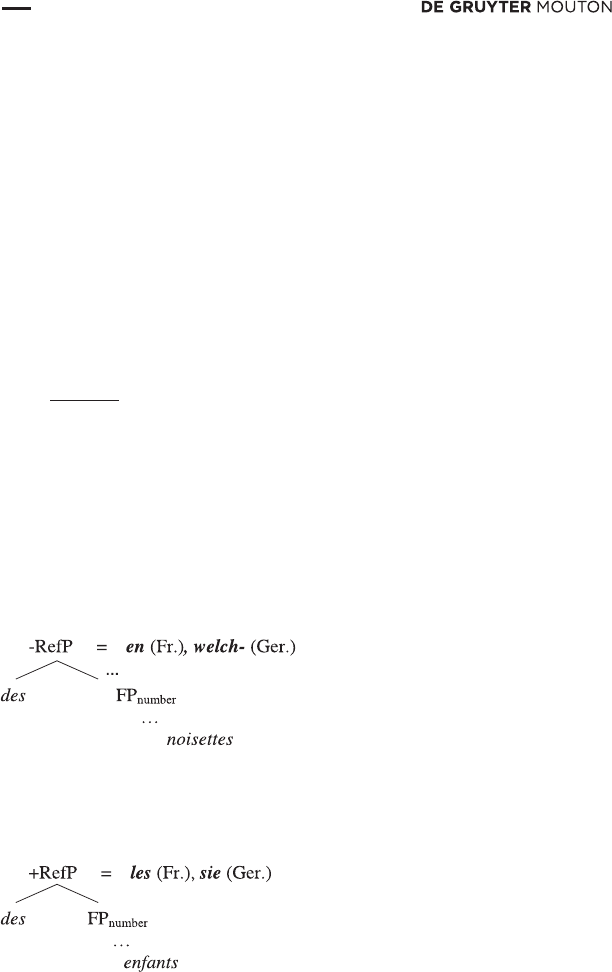

To account for the different uses of en in (19b-e), Ihsane (2013) proposes the

layered noun phrase structure in (20). In (20), the layer replaced by en can be ˗RefP,

the projection hosting the partitive article in examples that are non-referential like

(14) with des or (18) with du. The layer replaced by en can also be FP

de

,in

quantitative and negated constructions like (9b) and (16)–(17) respectively

8

:

(20)

(+RefP) > … ˗RefP > FP

number

> (FP

quantity

) > (FP

de

) > (FP

count

)>NP

The structures of the non-referential des noisettes in (14) and of beaucoup de N in

(19d) are shown below:

(21)

(22)

8 Labels adopted from Ihsane (2013: 29). FP stands for Functional Projection and the projec-

tions in parentheses represent the ones that are not always projected in the nominal structure.

“Number” refers to grammatical number, i. e., singular/plural, whereas FP

quantity

hosts quanti-

fiers such as numerals and beaucoup/peu ‘many/few(little)’ in its specifier position. As for the

projection labelled FP

count

, it contains grammatical items leading to an individuated reading (in

opposition to the mass interpretation), typically elements like the indefinite article (which then

moves higher in the structure) and the plural morpheme on the noun (cf. Borer 2005). + RefP

and – RefP represent a split DP, where + RefP would be analogous to Longobardi’s (2001) DP

encoding referentiality.

Convergence and divergence 775

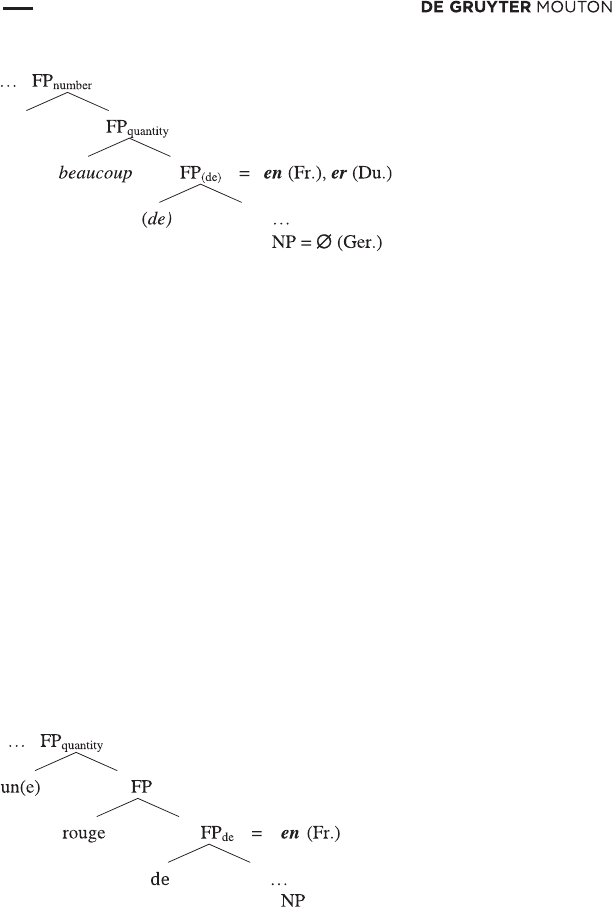

The structure postulated in (22) is also advocated for other quantitative

examples, typically with numerals (trois livres ‘three books’)orwithplusieurs

‘several’ (pl usieurs livres ‘several books’), the idea being that such examples

contain an implicit de ‘of’. Evidence for this assumption comes from examples

like (23), where de ‘of’ is overt and where de bonnets ‘of hats’ is no t disl ocated.

Examples with a dislocated de-phraselike(24)(Lagae2001)supportthe

presence of de in the spine of the struc ture: t he dislocated constituent is

taken to be a repetition of the constituent replaced by en (Kayne 1977;

Milner 1978):

(23) … ça fait deux de bonnets que je perds.

… it makes two of hats that I lose

(Bauche 1951: 79–80 quoted in Kayne 1977: 112 fn.)

(24)

J’ en ai lu deux / plusieurs, de livres.

I

EN

have read two / several of books

‘I read two/several books.’

The structure in (20) further allows us to capture the contrast between the

examples containing a partitive article when it comes to pronominalization

(recall (14)–(15)): en can replace ˗RefP, but not +RefP, which is replaced by a

definite pronoun (cf. Gross 1973):

(25)

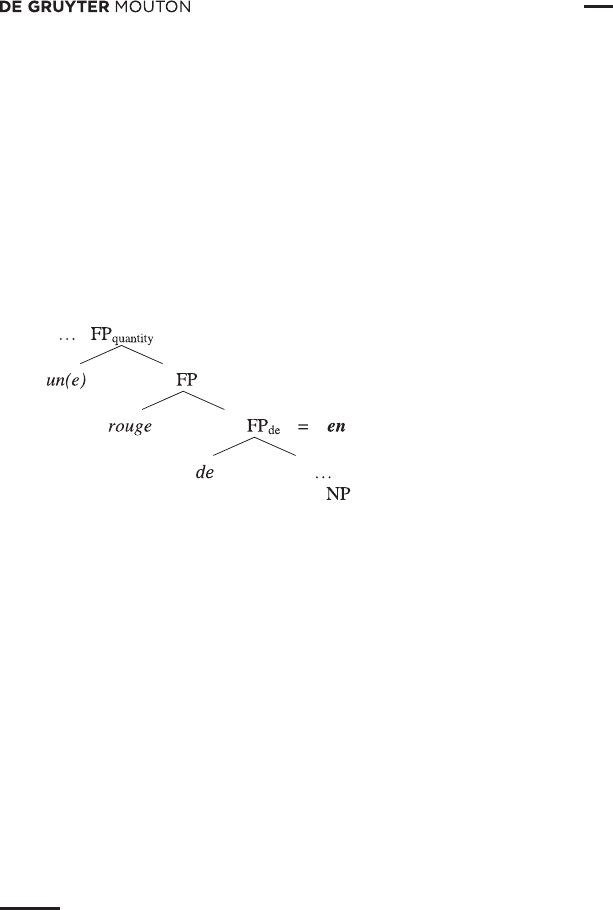

As for the combination of en with an indefinite object noun phrase containing an

adjective, as in (12), we adopt Cinque’s (2010) analysis, according to which

adjectives are merged in the specifier of a functional projection dominating

NP, with the NP moving to a higher position to yield a postnominal position

of the adjective. Sleeman (1996) shows that only so-called classifying adjectives

can be combined with en (Barbaud 1976; Ronat 1977). Just like quantifiers, these

adjectives allow de in dislocation, as shown in (26). If the de-phrase reiterates

776 Petra Sleeman and Tabea Ihsane

what en replaces, as assumed here, it suggests that, in the contexts under

discussion, de is present in the structure in (20) (cf. (24)).

9

(26) J’ en ai acheté une rouge, de robe.

I

EN

have bought a red of dress

‘I bought a red dress.’

We therefore propose that the structure can also contain an FP

de

following the

adjective:

(27)

Based on the above discussion, we suggest that the conditions that are neces-

sary but not sufficient for en to be used can be formulated as follows:

(28) a. en replaces constituents headed by de (which can be a preposition or not).

b. en replaces constituents that are not referential (and/or not sub-parts of

a referential nominal, cf. (13)).

c. en moves up as a clitic to a verbal host.

10

In the next section, we present our methodology.

9 As a reviewer observes, this does not imply that all dislocated de-phrases admit a pronoun en:

(i) a. Je (*en) préfère celle-là, de robe.

I EN prefer this-there of dress

b. Je (*en) préfère la tienne, de robe.

I EN prefer the yours of dress

10 This is a simplification: in imperatives, en follows the verb (Prends-en! ‘Take of it!’), and a

distinction between finite and non-finite verbs should be made, as en may precede the infinitive

(Tu devrais en prendre. ‘You should take of it’).

Convergence and divergence 777

3 Methodology

3.1 The test

In Sleeman and Ihsane (2017), we used a Grammaticality Judgment Task to test

L2 advanced learners’ knowledge of the use of en. The test consisted of 92

French items including 8 fillers.

11

A brief context/situation was provided in

brackets when necessary, as in the following example:

(29) [Context : I say: Je vois des enfants dans la cour.

I see of.the children in the yard

Ce sont Julie, Pierre et Sophie.]

these are Julie, Pierre and Sophie

‘I see some children in the yard, namely Julie, Pierre and Sophie.’

[Situation: You also see Julie, Pierre and Sophie.]

Tu dis : J’ en vois aussi.

you say I

EN

see also

‘I also see some.’

o Correct

o Incorrect

Several variants of the items were presented in the test, with different targets for

which the participants had to decide if they were correct or incorrect.

12

For (29),

for instance, there was also a version in which the students were asked if the

option Je les vois aussi ‘I also see them’ is correct or not.

For the present paper, we used the results of 54 of the 92 test items. We were

interested in the following topics:

A. The relation between partitivity and indefiniteness.

B. The relation between partitivity and non-referentiality.

C. The relation between partitivity and quantification.

D. The distinction between a quantitative and a partitive reading.

11 Since the test contained many varied test items, illustrating different uses of en, containing

other pronouns, no pronoun or an NP, we considered that they were different enough not to

trigger an accommodation effect and did not use more fillers.

12 In the introductory test that we presented to the participants it was made explicit that these

terms might be too strong for some cases.

778 Petra Sleeman and Tabea Ihsane

For A, we analyzed whether our participants accepted the use of (i) en in

combination with a definite DP containing an adjective, as in (13). There were 6

items: 3 with en and 3 without en.

For B, we analyzed whether our participants accepted the use of (ii) en in

combination with a non-referential plural noun phrase, as in (14), and rejected

the use of (iii) en with a referential noun phrase, as in (15). We also tested the

acceptance of (iv) en with indefinite mass nouns, as in (18), which are non-

referential. In the three cases, there were 6 items, half of them contained en and

half of them le(s) ‘it’/’them’.

For C, we analyzed the acceptability of the use of (v) en with an indefinite

noun phrase in object position introduced by a quantifier, as in (11). There were

6 test items, half of which contained en, and half of which contained only the

elliptical noun phrase but no en. Since classifying adjectives also create subsets,

just like quantifiers, and therefore in a sense may be related to quantification

(Sleeman 1993), we analyzed the acceptance of the use of (vi) en with a classify-

ing adjective in an indefinite noun phrase, as in (12). There were 6 items, 3 with

and 3 without en. Since negation can also count as a quantifier, we analyzed the

acceptance of the use of (vii) en with negated singular and plural noun phrases,

as in (16) and (17). Negated noun phrases are always non-referential. Therefore,

they can also be used for B. For each category, there were 6 items, half of which

contained en and half of which contained le or les.

For D, we analyzed the acceptance of (viii) en in quantitative contexts, as in

(9b), and in partitive contexts, as in (9a). For both categories, there were 3

sentences.

Since we were interested in the expression of partitivity (in a broad sense as

explained above) in other languages, with and without a partitive pronoun such

as en/er, we created a test in Dutch and a test in German, with sentences similar

to the French ones. In the German test we used welch- in a part of the sentences,

cf. (8), viz. those in which en replaces a constituent without an overt quantifier

(i. e., du/des constituents and negated mass/plural indefinite noun phrases). In

the Dutch and the German tests, we gave, for some categories, three variants

instead of two: er (Du)/Ø (Ger), definite pronoun, noun. The third option is

illustrated below:

(30) [Context: Isabelle: Haben Sie sich Zucker von Ihrem Nachbarn

have you yourself sugar of your neighbour

geliehen?]

borrowed

‘Did you borrow sugar from your neighbour?’

Convergence and divergence 779

Mélanie: Ja, er hat mir Zucker geliehen.

yes he has me sugar lent

‘Yes, he has lent me sugar.’

For the quantitative versus partitive interpretation there were 9 items in German

and Dutch instead of 6. The reason is that the partitive interpretation can also be

expressed in these languages by means of a pronominal adverb, davon in

German and ervan in Dutch.

(31) [Situation: Yesterday I saw five students.]

Vandaag heb ik twee ervan opnieuw gezien. Pron. adv. ervan

today have I two of.them again seen

‘Today I saw two of them again.’

For negated singular and plural noun phrases in German, we added 4 sentences

containing the negator kein-:

(32) [Context: Louis: Haben sie kein Geld?]

have you no money>

‘Don’t you have money?’

Sara: Nein, ich habe keins.

no I have none

‘No, I don’t have any.’

For Dutch, we wanted to know if er is also only accepted in indefinite contexts, if

it is accepted in non-referential contexts but not in referential contexts, if it is

related to quantification in the same way as French en, and if both a partitive

and a quantitative interpretation are accepted for er.

What interested us for German was to know if, in spite of the absence of a

partitive pronoun like en, German is able to express partitivity in the same way as

French, if a distinction between a quantitative and a partitive interpretation can

be made, and a distinction between a referential and a non-referential reading.

The Dutch test had been created to test the knowledge of er of the Dutch L2

learners of French tested in Sleeman and Ihsane(2017),becausewewereinterested

in transfer in L2 acquisition. The Dutch test contained 88 questions including 16

fillers. For the purpose of this paper, we used the results of 72 test items, excluding

thefillers,forthesamecategoriesas the ones specified above for French:

(i) er with a definite article + adjective (6 items for Dutch)

(ii) er with non-referential plural indefinites (9 items for Dutch)

(iii) er with referential plural indefinites (9 items for Dutch)

780 Petra Sleeman and Tabea Ihsane

(iv) er with indefinite mass nouns (9 items for Dutch)

(v) er with quantified noun phrases (6 items for Dutch)

(vi) er with an indefinite article + adjective (6 items for Dutch)

(vii) er with negated singular and plural indefinites (18 items for Dutch)

(viii) er with a quantitative or a partitive interpretation (9 items for Dutch)

The German test was created for the purpose of the present paper. It contained

82 test items including 15 fillers. We tested whether partitivity can also be

expressed in the absence of a partitive pronoun. We also tested whether

welch- can have the same function as en replacing a du/des-constituent and a

negated mass/plural noun phrase:

(i) Ø with a definite article + adjective (3 items for German)

(ii) welch- with non-referential plural indefinites (9 items for German)

(iii) welch- with referential plural indefinites (9 items for German)

(iv) welch- with indefinite mass nouns (9 items for German)

(v) Ø with quantified noun phrases (3 items for German)

(vi) Ø with an indefinite article + adjective (3 items for German)

(vii) welch- with negated singular and plural indefinites (22 items)

(viii) Ø with a quantitative or a partitive interpretation (9 items for German)

Examples for Dutch and German will be provided with the results in Section 4.

3.2 The participants

The French test had been filled in by 8 native speakers of French, who served as

a control group in Sleeman and Ihsane’s (2017) study on the acquisition of en by

Dutch learners of L2 French.

13

The Dutch test had been filled in, for the same

study, by the experimental group, Dutch advanced students of French. On the

basis of a questionnaire, we eliminated some participants and analyzed the data

of 23 participants: 13 undergraduate students and 10 graduate students. The goal

of this test was to study transfer from the use of Dutch er to French.

The German test was filled in by 40 monolingual native speakers of

German, mainly living in Germany, but also in the Netherlands and four of

13 Although the number of native speakers of French is rather low, their judgments are

consistent and correspond to a high degree to what is described in traditional grammars and

the linguistic literature. For reasons of comparability with the results of Sleeman and Ihsane

(2017), we decided therefore not to add more participants to the group of French native speak-

ers. This means, however, that we will have to be careful with the interpretation of the statistical

analysis that we will present in the next section.

Convergence and divergence 781

them living in Switzerland. We have not detected differences in the results of

these groups.

4 Presentation of the results

In this section, we present the analysis of the data per category, as classified in

Section 3.1.

14

(i) Definite article + adjective

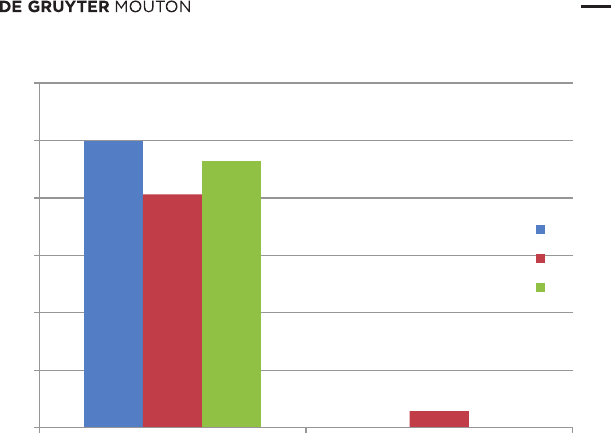

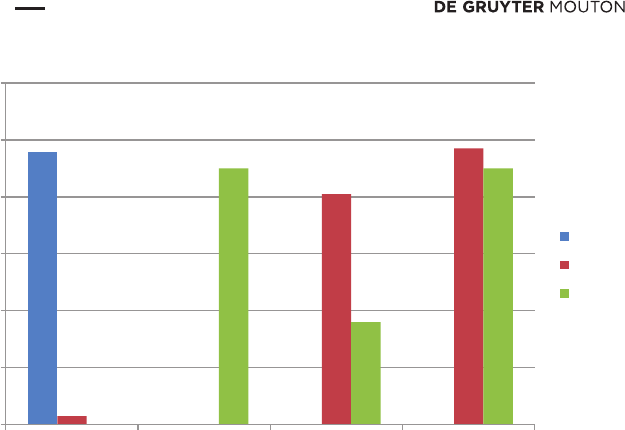

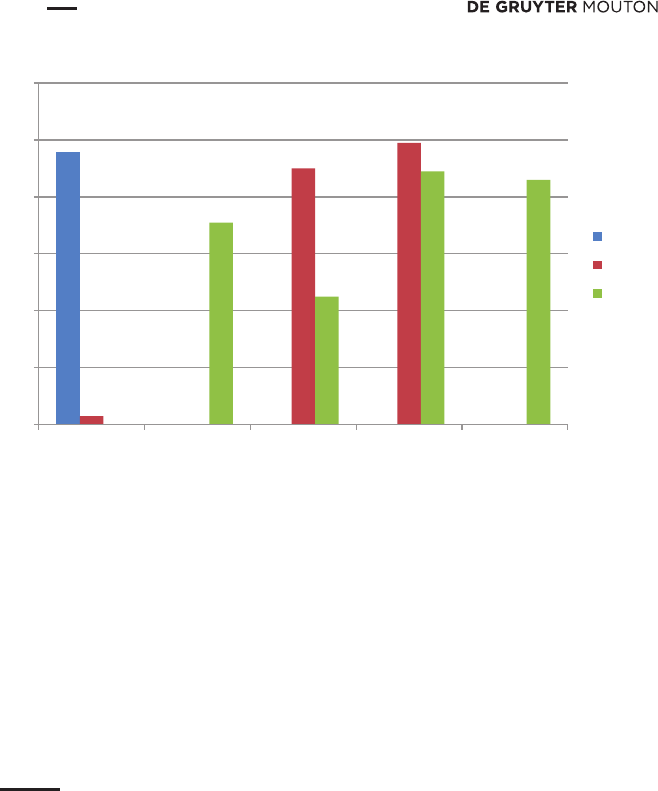

Figure 1 shows that in the three languages an elliptical noun phrase introduced

by a definite article and containing an adjective, as in (13) or (33), is accepted by

the participants. It is, however, significantly less accepted in Dutch than in

French (p = 0.011) or in German (p = 0.001). We will come back to this point

in the discussion. If the sentence contains a partitive pronoun, it is not accepted

by the native speakers of French (0%) nor by the native speakers of Dutch (cf.

(13)) vs. ((34)) below) in the test:

(33) [Situation: Julia has chosen the yellow bike from the catalogue.]

Anna hat das grüne aus dem Katalog ausgewählt.

Anna has the green from the catalogue chosen

‘Anna chose the green one from the catalogue.’

(34)

[Situation: John has caught three hares.]

Hij heeft (*er) de derde in het bos gedood.

he has

ER

the third.one in de wood killed

‘He killed the third one in the woods.’

(ii) Non-referential plural NPs

14 Most of the percentages that we present for French can also be found in Sleeman and Ihsane

(2017), but for criterion (viii), we did not make a distinction between the partitive and quanti-

tative interpretations. The Dutch data are analyzed in more detail than in Sleeman and Ihsane

(2017). Another difference is that Sleeman and Ihsane (2017) provided percentages in terms of

accuracy of acceptance or rejection by the L2 learners of French and the native speakers of

French and Dutch, establishing a norm for correctness for each sentence. In the present paper,

we give percentages of acceptance of sentences without reference to a norm. This means for

instance that whereas in Sleeman and Ihsane (2017) the percentage of (correct) rejection by the

native speakers of French for context (i), the combination of en with a definite article and an

adjective, is 100%, in Figure 1, the percentage of acceptance is 0%.

782 Petra Sleeman and Tabea Ihsane

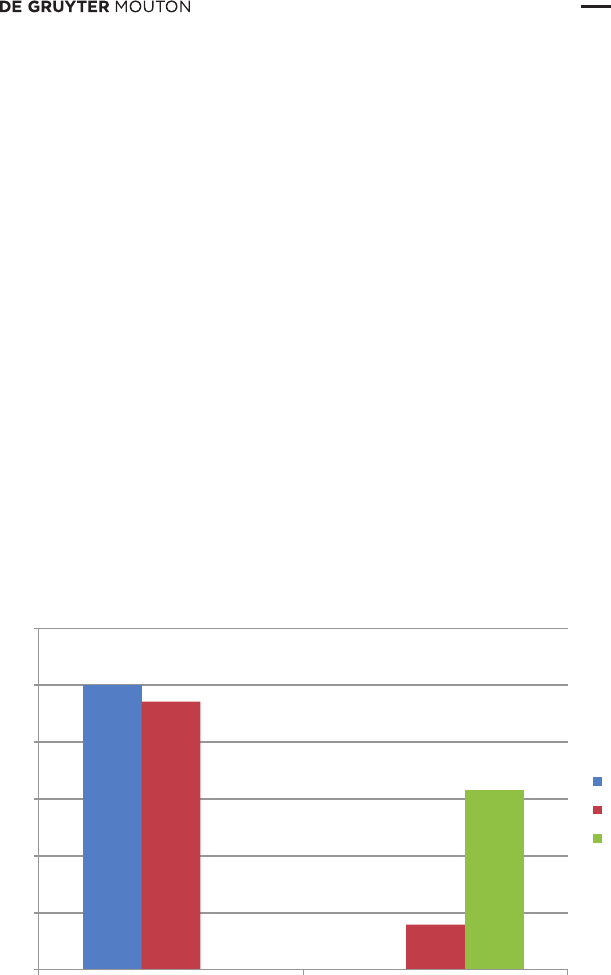

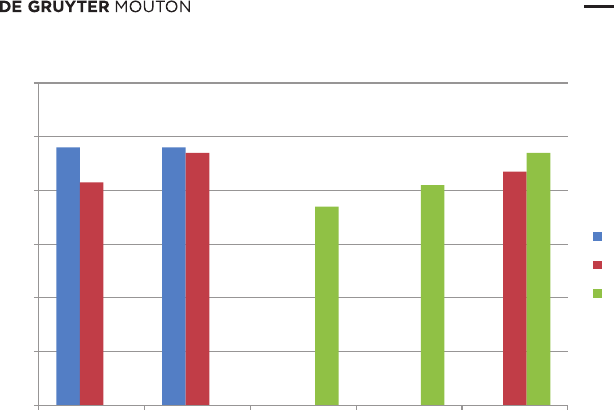

Figure 2 shows that with non-referential noun phrases the German participants

accept welch- (cf. (8)) where in French en is accepted (cf. (14)). In this context

the Dutch participants do not accept er (cf. (35)). In Dutch (cf. (35)) the use of

the definite pronoun is accepted significantly more than in French (p = 0.001)

or in German (p = 0.001). For Dutch and German, we also investigated whether

the participants accepted the use of a full NP (cf. (35c)), which they do, as the

figure shows.

(35) [Situation: At the wedding. all guests may take some flowers from a basket

to throw at the bride and the bridegroom. Julia decides to throw flowers.]

Michelle says:

a. *Ik gooi er ook.

I throw

ER

too

b. ?Ik gooi ze ook.

I throw them too

‘I throw them too.’

c. Ik gooi ook bloemen.

I throw too flowers

‘I also throw flowers.’

(iii) Referential plural indefinite NPs

0

20

40

60

80

100

120

ØEN

/

ER

French

Dutch

German

Figure 1: Definite article + adjective.

Convergence and divergence 783

En, er and welch- are not accepted with referential NPs, as Figure 3 shows, but

significantly more in French (p = 0.002), cf. (15), or in German (p < 0.001), cf.

(36), than in Dutch (cf. (37)). In one of the three sentences of the Dutch and the

German test the NP (not tested for French) was preceded by a definite article.

The use of a bare NP is less accepted than the use of a definite article, both in

Dutch (p = 0.001) and in German (p < 0.001).

(36) [Context: I say: Ich sehe Kinder auf dem Schulhof spielen.

I see children on the schoolyard play

Es sind Sara, Paul und Eva.]

it are Sara Paul and Eva

‘I see some children playing in the schoolyard, namely Sara,

Paul and Eva.’

[Situation: You see exactly the same children playing in the schoolyard.]

a. You say: * Ich sehe auch welche.

I see also some

b. You say: Ich sehe sie auch.

I see them too

0

20

40

60

80

100

120

EN/ER welch-

p

ronoun NP

French

Dutch

German

Figure 2: Non-referential plural NPs.

784 Petra Sleeman and Tabea Ihsane

(37) [Context: I say: Ik zie kinderen op het schoolplein spelen.

I see children on the schoolyard play

Het zijn: Jelle, Fleur en Ina.]

these are Jelle, Fleur and Ina

‘I see some children in the schoolyard, namely Jelle, Fleur and

Ina.’

[Situation: You see exactly the same children playing in the schoolyard.]

You say: Ik zie ze ook.

I see them too

(iv) Mass nouns

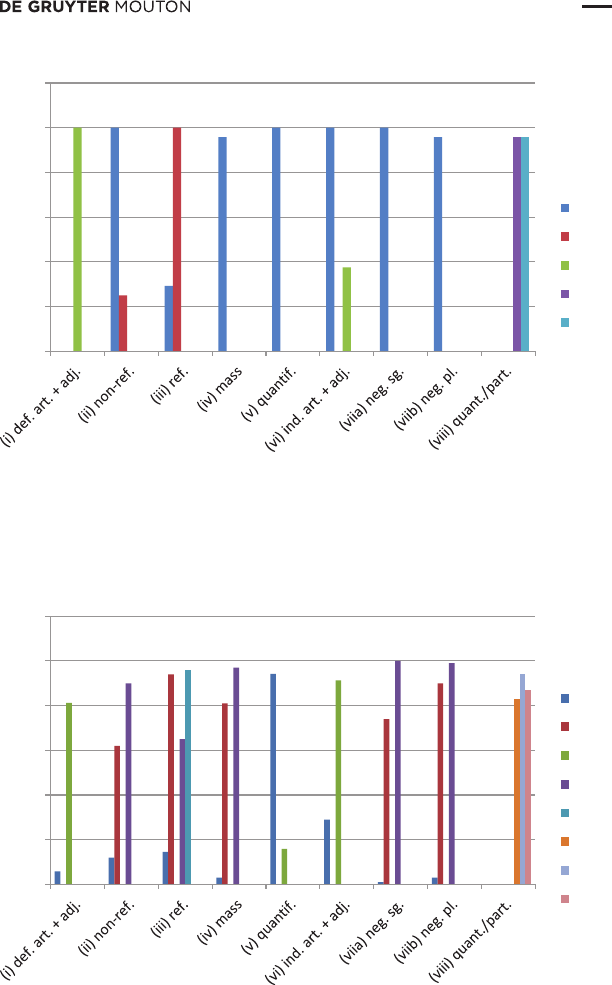

As for mass nouns, we see in Figure 4 that whereas the use of en and welch is

accepted in French (cf. (18)) and German (cf. (39)), the use of er is not in Dutch

(cf. (38)). The use of a definite pronoun is more marginally accepted in German

than in Dutch. This difference is significant (p < 0.001). In French, it is not

accepted (0%). The acceptance of the use of NPs was only investigated for

Dutch and German (cf. (30)). NPs are accepted for both languages.

0

20

40

60

80

100

120

EN/ER welch-

p

ronoun NP DP

French

Dutch

German

Figure 3: Referential plural NPs.

Convergence and divergence 785

(38) [Context: Piet: Hebben de katten melk gedronken vanmorgen?]

have the cats milk drunk this.morning

‘Did the cats drink milk this morning?’

Anna: Ja, ze hebben het/ melk gedronken. / *Ja, ze

yes they have it/ milk drunk yes they

hebben er gedronken.

have

ER

drunk

(39)

[Context: Child: Könntest du bitte Brot kaufen?]

could you please bread buy

‘Could you please buy bread?’

Mother: Nein, wir haben noch welches/ wir haben *es noch/ wir

no we have still

WELCHES

we have it still we

haben noch Brot.

have still bread

‘No, we still have bread.’

0

20

40

60

80

100

120

EN/ER welch-

p

ronoun NP

French

Dutch

German

Figure 4: Mass nouns.

786 Petra Sleeman and Tabea Ihsane

(v) Quantified elliptical object NPs

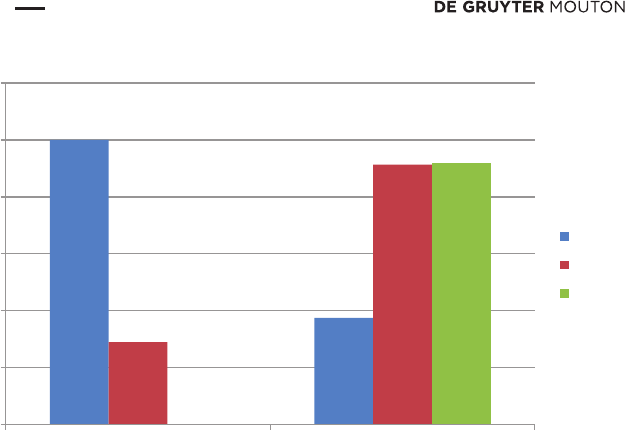

As illustrated in Figure 5, the use of the partitive pronoun is accepted both in

Dutch (cf. (6)), and in French (cf. (11)). The omission of the partitive pronoun is,

however, rejected in French (0% acceptance), as it is in Dutch (15%), although

this difference is significant (p = 0.041). In German, welch- cannot be used in

this context (not tested), but the omission of the noun is accepted only in 63% of

the cases (cf. (40)), which is, however, significantly more than in French (p <

0.001) and in Dutch (p < 0.001).

(40) [Ich werde einige Museen besuchen.] - Ich werde einige besuchen.

I will some museums visit I will some visit

‘[I will visit some museums.] I will visit some.’

(vi) Indefinite article + adjective

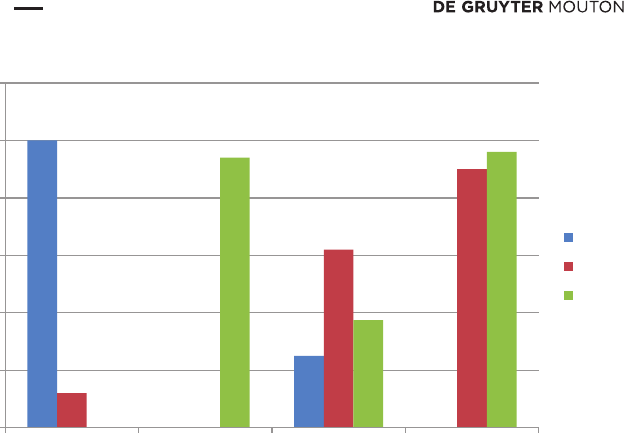

The use of the partitive pronoun in combination with an indefinite elliptical

NP + adjective is accepted by the French participants (cf. (12)), see Figure 6.

By the Dutch participants, the omission of the partitive pronoun is preferred

(cf. (41)). This also holds for the native speakers of German (cf. (42)).

0

20

40

60

80

100

120

EN

/

ER Ø

French

Dutch

German

Figure 5: Quantified object NPs.

Convergence and divergence 787

(41)

[Situation: Marie has bought a blue balloon.]

Paul heeft (*er) een rode gekocht.

Paul has

ER

a red.one bought

‘Paul bought a red one.’

(42)

[Situation: Julia has chosen a yellow bike in the catalogue.]

Anna hat ein grünes aus dem Katalog ausgewählt.

Anna has a green from the catalogue chosen

‘Anna chose a green one from the catalogue.’

(vii) Negated indefinite singular and plural NPs

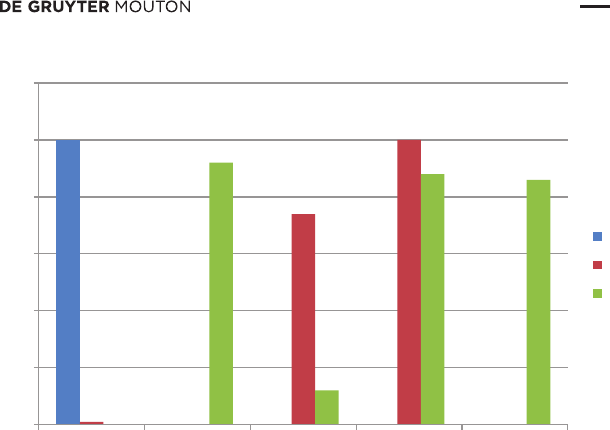

In Figure 7, we see that with negated singular elliptical NPs the native speakers

of French, cf. (16), and German, (cf. (44)), accept the use of en resp. welch-, but

that the Dutch participants strongly prefer the definite pronoun (cf. (43)). The

German native speakers marginally accept the use of the definite pronoun. The

French native speakers do not accept it at all (0%). The acceptance of the use of

an NP was investigated for Dutch and German, with a positive result. For

German, the acceptance of the negator kein- was furthermore tested and yielded

a positive outcome (cf. (32)).

0

20

40

60

80

100

120

EN

/

ER Ø

French

Dutch

German

Figure 6: Indefinite article + adjective.

788 Petra Sleeman and Tabea Ihsane

(43) Anna: Drink je geen bier?

drink you no bier

‘Don’t you drink beer?’

Jan: Nee, ik drink *er niet./ Nee, ik drink het niet/ Ik drink

no I drink

ER

not no I drink it not I drink

geen bier.

no beer

‘No, I do not drink any.’

(44)

Ann: Trinken Sie keinen Wein?

drink you no wine

‘Don’t you drink wine?’

Lucie: Nein, ich trinke nie welchen.

no I drink never

WELCH

‘No, I never drink any.’

A similar result is provided in Figure 8 for negated plural NPs, but the accept-

ance of welch- in this context is significantly lower than the acceptance of en

0

20

40

60

80

100

120

EN/ER welch-

p

ronoun NP kein-

French

Dutch

German

Figure 7: Negated singular elliptical NPs.

Convergence and divergence 789

(p < 0.001) and also than the acceptance of welch- with negated singular NPs

(p < 0.001).

15

We will come back to this point in the discussion section.

(viii) Quantitative or partitive interpretation

According to Figure 9, the quantitative interpretation is accepted by the participants

for both en (cf. (9b)) and er (cf. (45b)) below), but also, although to a minor degree,

in German, which does not use welch- in this context, the distinction is made (47).

This also holds for the partitive interpretation (cf. (9a), (45a)), even though in both

0

20

40

60

80

100

120

EN/ER welch-

p

ronoun NP kein-

French

Dutch

German

Figure 8: Negated plural elliptical NPs.

15 The welch- sentences consisted of two sentences containing nie(mals) ‘never’, and one

control sentence containing nicht ‘not’. The control sentence served to establish that the

combination of welch- with nicht is ungrammatical: sentence (i) was rejected by all native

speakers of German. The percentage of acceptance given in Figure 8 is based on the two

sentences containing nie(mals), one of which is illustrated in (ii):

(i) [Context: Fred: Haben sie heute Morgen keine Medikamente genommen?]

have you today morning no medicines taken

Patrick: *Nein, ich habe welche nicht genommen.

no I have

WELCHE

not taken

[Fred: Haven’t you taken any medicines this morning?] – Patrick: ‘No, I haven’t.’

(ii)

Liest du niemals Kriminalromane? Nein, ich lese nie welche.

read you never thrillers no I read never

WELCHE

‘Do you never read thrillers? No, I never do.’

790 Petra Sleeman and Tabea Ihsane

Dutch (cf. (31) and (45a)) and German (cf. (46)) the partitive interpretation can also

be expressed by a pronominal adverb: ervan/davon. German does not significantly

differ from French or Dutch in these three contexts.

(45) [Situation: Yesterday I saw five students.]

a. Vandaag heb ik er twee/twee ervan opnieuw Partitive er

today have I

ER

two/two of.them again

gezien.

seen

‘Today I saw two of them again.’

b. Vandaag heb ik er ook vijf gezien. Quantitative er

today have I

ER

also five seen

‘Today I also saw five (students, i.e., different students).’

(46)

[Situation: Last year we built fifty houses.]

Gestern haben wir zwei/zwei davon Pron. adv. davon

yesterday have we two/two of.them

abgerissen, weil sie schlecht gebaut waren.

torn.down because they badly built were

0

20

40

60

80

100

120

quantitative

EN

/

ER

partitive EN/ER quantitative Ø partitive Ø ERVAN/DAVON

French

Dutch

German

Figure 9: Quantitative or partitive interpretation.

Convergence and divergence 791

(Also gibt es jetzt noch 48 Wohnungen.)

therefore gives it now still 48 houses

‘Yesterday we tore down two houses because they were badly built. This

means that there are 48 houses left. ’

(47)

[Situation: Yesterday we tore down two houses because they had been

badly constructed.]

Heute haben wir drei abgerissen. Quantitative interpretation

today have we three torn.down

‘Today we have torn down three houses.’

5 Discussion

Besides a crosslinguistic comparison of the possibilities to express partitivity in

the three languages under study, our test has allowed us to compare alternative

constructions within the languages. Furthermore, we have not provided the

intuitions of one native speaker per language, as is often done in the linguistic

literature (often these are the author’s intuitions) nor have we simply copied

judgments provided in grammars or the linguistic literature. For French we have

checked judgments reported in the literature by means of a Grammaticality

Judgment Task. For Dutch and German, we have provided very few judgments

from the literature beforehand, the reason being that the 8 categories distin-

guished in Section 3 are barely discussed in Dutch and German grammars and

literature. A Grammaticality Judgment Task is an appropriate tool to explore

native speakers’ intuitions (Blume and Lust 2016) about the possibilities within

these categories, which we distinguished on the basis of what has been

described for French. Familiarity with this kind of tests or some metalinguistic

knowledge may have influenced the results. The Dutch informants were under-

graduate and graduate students of French, whereas most of the German partic-

ipants did not have any notion of linguistics. The French informants were

mainly, but not exclusively, linguists. Hereafter we discuss our results. For the

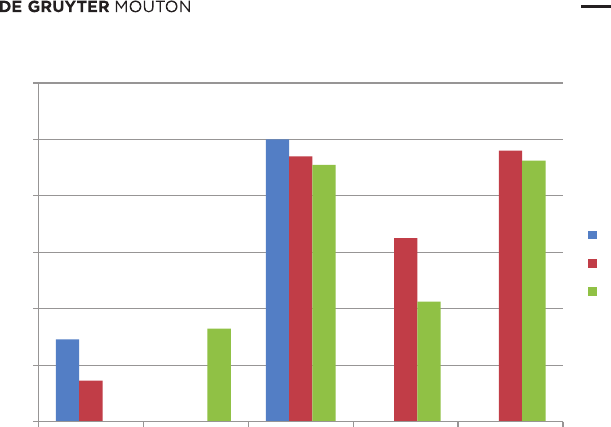

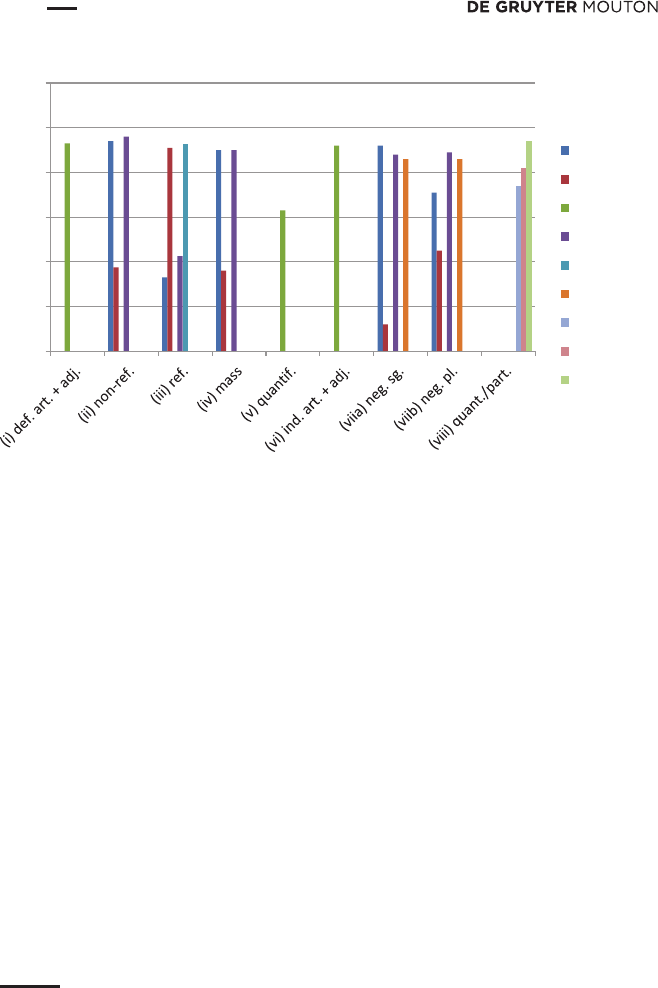

reader’s convenience, we first represent the results presented in the previous

section in Figures 10, 11 and 12 per language.

792 Petra Sleeman and Tabea Ihsane

0

20

40

60

80

100

120

en

def. pronoun

empty noun

quant. int.

part. int.

Figure 10: French data.

Category (i): partitive pronoun 0%; (iv) definite pronoun 0%; (v) empty noun 0%; (vi) empty

noun 0%; (viia) definite pronoun 0%; (viib) definite pronoun 0%.

0

20

40

60

80

100

120

er

def. pronoun

empty noun

NP

DP

quant. int.

part. int.

ervan

Figure 11: Dutch data.

Convergence and divergence 793

The context of definite article plus adjective (i) disallows the use of the partitive

pronoun; an elided noun is preferred.

16

The lower acceptance of the omission of

the noun in Dutch is due to the relatively low percentage of acceptance of one

sentence (44%), which may be due to another reason than the omission of the

noun.

With non-referential plural noun phrases (ii), standard Dutch does not

accept er, in contrast to Dutch dialects (cf. (7)), but prefers a definite pronoun,

significantly more than German (37,5%) and French (25%).

With referential noun phrases (iii) the use of a definite pronoun or a DP is

preferred in the languages under consideration. The use of an NP is less

accepted with referential noun phrases than with non-referential noun phrases.

In Dutch the use of er is rejected, but the use of en in French and welch-in

German is marginally accepted by the native speakers. The reason for this might

be that some contexts did not completely exclude the use of a non-referential

interpretation. Although the participants were categorical in rejecting (29) and

(36) – 0% acceptance for French and 2,5% acceptance for German – the other

0

20

40

60

80

100

120

welch-

def. pronoun

empty noun

NP

DP

kein

quant. int.

part. int.

davon

Figure 12: German data.

16 The non-acceptance of er with a definite article + adjective in Dutch may be related to the

non-acceptance of er with an indefinite article + adjective. It would then be due to the combi-

nation with an adjective. In sentences with a definite determiner + quantifier er is not accept-

able either: *Ik heb er deze drie in de winkel gekocht ‘I have (

ER

) these three in the shop bought’,

which shows that er cannot be combined with a definite determiner.

794 Petra Sleeman and Tabea Ihsane

two contexts may also have favored a non-referential interpretation. In one of

the contexts en was accepted in 37,5% of the cases and welch- in 64%; in the

other context en was accepted in 50% of the cases and welch- in 37,5%.

17

Notice

however that 13 of the 40 German participants made the referential versus non-

referential distinction in all contexts by accepting welch- in the 3 non-referential

sentences and a definite pronoun in the 3 referential sentences. The significantly

lower acceptance rate of er in Dutch with respect to en and welch- in referential

contexts is due to the fact that er is not accepted in non-referential contexts

either. The interpretation of a referential context as a non-referential context will

not make the use of er more acceptable.

The results for mass nouns (iv) are the same as for non-referential plural

noun phrases, but the use of a definite pronoun in Dutch is more accepted with

mass nouns (81%) than with non-referential plural NPs (62%). For German the

acceptance rate of a definite pronoun for mass nouns (36%) is comparable to the

one for non-referential plural nouns (37,5%) and lower than for Dutch (probably

because German offers the alternative welch-), but interestingly, we observed a

difference among the singular definite pronouns: for es ‘it’ we observed 2,5% of

acceptance, for ihn ‘him’ 40% and for sie ‘her’ 65%.

With quantified noun phrases (v) in French and Dutch the partitive pronoun

is required according to prescriptive grammar. This is confirmed by our data. In

German the omission of the noun is accepted in only 63% of the cases. If we take

into consideration the omission of the noun in other categories under study, the

percentage increases. In category (viii) the omission of the noun is accepted for

German in 74% of the cases in the quantitative interpretation and in 82% in the

partitive interpretation. In category (vii) the acceptance of the omission of the

noun with the negator kein- is 86%. For the three categories the acceptance of

the omission of the noun is on average 77%. The omission of the partitive

pronoun is accepted in 15% of the cases in Dutch, which is a significant differ-

ence with French (0%). This may be due to the choice of the quantifier in two of

the sentences, because in the third sentence (with the negator geen ‘no’) there

was 0% of acceptance.

18

17 The marginal acceptance of welch- with referential noun phrases may also be related to the

acceptance of welch- by 11 of the 40 native speakers of German in the following context, which

was used as a filler: [Sophie sieht die Kinder spielen.] – Sophie sieht welche spielen.

18 These two quantifiers (meerdere ‘several’ and enkele ‘some’) take the substantivized form

meerderen and enkelen if they refer to humans, in which case there are speakers who do not use

er (Sleeman 2013, fn. 6). This may have caused the acceptance of meerdere and enkele without

er when they refer to objects.

Convergence and divergence 795

Whereas in category (vi) for French the use of en with an indefinite article +

adjective is accepted, its omission is not completely rejected either. This might be

due to the fact that in spoken French, the omission of en is accepted in this context

by some speakers of French. Dutch and German accept the simple omission of the

noun without a supplier. For Dutch a rate of 29% of acceptance for the use of er with

an indefinite article + adjective is somewhat surprising. In some Dutch dialects, the

use of er with an indefinite determiner + adjective is, however, accepted (Sleeman

1998; Kranendonk 2010). Although our participants were probably not speakers of

these dialects, the combination of er and indefinite article + adjective may not have

shocked some of the participants for this reason. Out of the 23 Dutch participants, 6

accepted 2 or 3 sentences with er. That 7 participants accepted er in one of the

sentences may also be due to other reasons. The small word er may not have been

noticed when reading the sentence or it may have been interpreted as a locative er,

although we added an explicit locative modifier to the test sentences in order to

prevent a locative interpretation of er (cf. fn. 2).

With negated nouns (vii), the three languages behave as in the case of non-

referential nouns and mass nouns. In German, however, welch- is accepted

significantly less with plural NPs (71%) than with singular NPs (92%).

19

With

the negated plural NPs, the use of a definite pronoun is accepted in 45% of the

cases. This percentage comes close to the percentage of acceptance of the use of

the definite pronoun with non-referential plural NPs (37,5%). In both cases the

definite pronoun is the plural form sie. In the singular, there is a difference

between the acceptance rate of a definite pronoun with negated indefinite

singular NPs (12%) and mass nouns (36%). In the test sentences with a singular

negated NP, the pronoun was twice ihn ‘him’ (22,5% and 11% of acceptance

respectively), and once the neutral pronoun es ‘it’ (0% of acceptance). The rate

of acceptance of sentences with ihn is lower with a negated indefinite singular

19 Since the use of nicht ‘not’ is impossible in combination with welch-, we used nie(mals)

‘never’. For negated plural NPs there were two sentences containing nie(mals) ‘never’ and one

control sentence containing nicht ‘not’, cf. fn. 16. The use of nie(mals) may sometimes have

sounded unnatural. Sentence (i), in which welch- has a negated plural NP as its antecedent, was

accepted by only 47,5% of the native speakers of German. This has reduced the percentage of

acceptance of welch- in the context of negated plural NPs.

(i) [Context: Claire: Als Sie in der Bretagne Urlaub gemacht haben, haben Sie da keine Austern

gegessen?]‘When you were in Brittany for a holiday, didn’t you eat any oysters?’

Paul: Nein, ich habe nie welche gegessen.

no I have never

WELCHE

eaten

‘No, I never ate oysters.’

796 Petra Sleeman and Tabea Ihsane

NP than with a mass noun. With mass nouns, there was one sentence containing

ihn (40% of acceptance). With mass nouns, the test sentence containing es was

accepted in 2,5% of the cases and the one containing sie, i. e., a feminine

singular pronoun, in 65% of the cases. The differences in the acceptance rates

of the different forms of the definite pronouns are intriguing. In future work, we

will investigate in more detail the role of gender and number in our results.

For Dutch, the definite pronoun was accepted to an equal rate with singular

(mass, negated mass noun) and plural (non-referential, negated) elliptical NPs:

77% and 76%. In the singular we always used the neutral pronoun het ‘it’,

because, according to Audring (2009), in present-day Dutch common, i. e.,

non-neuter, mass nouns are replaced by het and not by the masculine pronoun

hem ‘him’ or the feminine pronoun haar ‘her’. In our test, het replaced twice a

neuter noun and four times a common noun. The percentages of acceptance

were comparable: 76% and 78% respectively, which corroborates Audring’s

claim.

In the three languages a distinction between a quantitative and a partitive

interpretation is made (viii). The relatively low percentage for the acceptance of

the quantitative interpretation in German may be due to the results of one

sentence, which was only accepted by 58% of the participants.

20

In the next section, we make use of a broader classification to compare our

results for the three languages.

6 Modelling the results

In Section 3, we grouped our subcategories (i–viii) into four broad categories:

A. The relation between partitivity and indefiniteness (i).

B. The relation between partitivity and non-referentiality (ii–iv).

C. The relation between partitivity and quantification (v–vi).

D. The distinction between a quantitative and a partitive reading (viii).

20 One of the participants observed that the sentence is only grammatical if ein is stressed:

‘one’.

(i) [Situation: Yesterday a/one student came to see me.]

Heute habe ich zwei gesehen.

today have I two seen

‘Today I saw two students.’

Convergence and divergence 797

Our results show that in all three languages a distinction is made between

partitivity, in the broad sense as used in this paper, and indefiniteness (A): en, er

and welch- are only used in indefinite contexts.

In addition, the results show that there is a relation between partitivity and

non-referentiality (B), at least for French and German: with non-referential

plural nouns and with mass nouns en resp. welch- are preferred. Standard

Dutch does not make the distinction: the use of the definite pronoun is preferred

with both referential and non-referential noun phrases like kinderen ‘children ’

(48), which is ambiguous between the two readings.

(48) [Situation: I see a group of identified children] or [Situation: I see a group

of unidentified children.]

Ik zie kinderen op het strand.

‘I see children on the beach.’

In French, the use of the definite pronoun is not or marginally accepted with

non-referential noun phrases and with mass nouns. This is confirmed by the

results of the negated noun phrases, which are non-referential. In terms of

Ihsane’s (2013) DP structure presented in Section 2.2, this means that the

distinction of a non-referential portion of the DP can be overtly expressed in

French (en) and in German (welch-):

(49)

French and German distinguish a non-referential interpretation from a referen-

tial interpretation by using a definite pronoun in the latter case:

(50)

As for Dutch, it is similar to French and German regarding the use of a definite

pronoun for the referential interpretation, suggesting that the referential portion

798 Petra Sleeman and Tabea Ihsane

of the noun phrase can be expressed by a definite pronoun as in (50).

21

The

question that arises is whether Dutch also has a structure like (49) for non-

referential constituents: indeed, since in such examples it is ze that is used, it is

not obvious that Dutch has a specific structure for non-referential constituents.

However, as kinderen ‘children’ in (48) can be both non-referential and refer-

ential, it shows that Dutch does make a semantic distinction between non-

referential and referential noun phrases. Therefore, we propose that the struc-

ture of the former is as in (49), even if the distinction referential/non-referential

is not made by means of different pronouns. These cases would be examples of

syncretism where an element, like ze, is used in different contexts and repre-

sents different structures.

22

The fact that er is not accepted in non-referential

constructions may explain the broad acceptance of definite pronouns in Dutch.

23

Both French and Dutch use a partitive pronoun with a quantifier (C). The

corresponding sentences in German have an elided noun. Although the percent-

age of acceptance is relatively low with quantifiers, the rate of acceptance of an

elided noun with the quantifier kein- and in a quantitative or partitive interpre-

tation shows that elision of the noun is a way to express partitivity in German, in

the absence of a partitive pronoun. The structure would be as in (51), where FP

de

is restricted to French (in Dutch er replaces the projection selected by the

quantifier):

21 In the Dutch Reference Grammar (ANS, Algemene Nederlandse Spraakkunst, Haeseryn et al.

1997) it is observed that in Belgium and the southern part of the Netherlands, er can be used by

part of the native speakers of Dutch with a non-referential interpretation and a definite pronoun

or a DP with a referential interpretation. These speakers are classified as group x. The other

group, group y, does not know the non-referential use of er. Our participants, most of which

probably come from the Northwest of the Netherlands, are speakers of “group y”.

22 That a “definite” pronoun is not always referential is a known phenomenon: in French for

instance, le ‘it’ can replace a sentence (Je le sais ‘I know it’) which is not strictly speaking

referential. In the same way, a “definite” article is not always definite (prendre le train ‘take the

train’). Such cases are sometimes referred to as weak definites (Aguilar-Guevara and Zwarts

2011).

23 Barbiers (2017) also distinguishes ze from er in Dutch, but from a different perspective. He

distinguishes quantitative ze, as in (i), from quantitative er:

(i) Ik heb ze alle twee gelezen.

I have them all tworead

‘I read both.’

Similarly to our approach, Barbiers argues that pronominalization of Q-ze and pronominaliza-

tion of Q-er involve different portions of the noun phrase: a higher DP in the case of Q-ze and a

lower DP in the case of Q-er.

Convergence and divergence 799

(51)

With negated constituents, the results differ from (51): welch- in German patterns

with en in French and is accepted, whereas er in Dutch is rejected, as for context (ii).

This is not surprising since these constructions are also non-referential (cf. (49)).

These results support the fact that en in French depends on non-referentiality rather

than on the quantificational character of the construction or on the underlying

presence of de ‘of’ and suggests that it is also the case of welch- but not of er. What

seems crucial for the use of er is the presence of a quantifier.

With classifying adjectives, er is often not accepted, suggesting that, in

Dutch, classifying adjectives are not as quantifying as quantifiers; otherwise er

should be fully accepted since a quantifier seems to be needed for er to be

possible. In addition, Dutch allows nominal ellipsis with adjectives, like

German. In both Dutch and German, nominal ellipsis depends on the inflec-

tional properties of the adjective (e. g., Muysken and van Riemsdijk 1986; Kester

1996), whereas in French nominal ellipsis with or without en depends on the

partitive interpretation of the adjective (Sleeman 1996; Bouchard 2002). In Dutch

and German, the FP

de

is not projected.

(52)

In structure (51), both French en and Dutch er can have a quantitative interpre-

tation and a partitive interpretation (D). Even if in German there is no pronoun,

both interpretations are accepted as well.

The above discussion shows that welch- in Standard German is found in the

counterparts of the non-referential complements with the partitive article in French.

The constructions in which welch- is found are all complete non-referential nominal

800 Petra Sleeman and Tabea Ihsane

phrases. In other words, welch- cannot replace subparts of the nominal phrase. Er,

in contrast, only replaces a portion of the nominal structure, and this only with a

quantified element. As for en, it is accepted in both contexts, and also with

classifying adjectives.

7 Conclusion

In this paper, we have studied the notion of partitivity in a specific way: we have

focused on the so-called partitive pronoun en in French and studied eight

contexts in which en is accepted or disallowed. Our objective was to find out

how other languages, with a similar partitive pronoun like Dutch, or without

such a pronoun like German, behave in analogous contexts and to formalize the

results in the model developed in Ihsane (2013) in which the partitive pronoun

can replace different portions of the nominal structure.

This new crosslinguistic study is based on the results of a Grammaticality

Judgment Test taken by native speakers of French, Dutch and German. Our

overall finding is that the subtleties of the French partitive pronoun en can

also be expressed in Dutch and German, but in partially different ways. Our

investigations show that German, which does not have a partitive pronoun such

as en or er, often uses no lexical item in the contexts studied, i. e., ⊘, where

these overt pronouns are found, but that welch- partially has the same function

as en, which could mean that standard German does have a partitive pronoun

after all. Our results also show that (non)-referentiality correlates with partitiv-

ity: non-referentiality can be expressed by a pronoun, both in German and in

French, with welch- and en respectively, although the former is much more

restricted in the expression of partitivity than the latter. Dutch on the other

hand does not explicitly make a distinction between non-referential and refer-

ential noun phrases, at least in its standard. Er cannot be used with non-

referential noun phrases. However, our results suggest that definite pronouns

are relatively more accepted with referential noun phrases and the repetition of

the NP more with non-referential noun phrases. Although German has welch-to

express non-referentiality versus referentiality, we found the same tendency for

definite pronouns and NPs in German as in Dutch, although to a lower degree.

We also observed that Dutch er and the simple omission of the noun in German

both allow a quantitative and a partitive interpretation, just like French en.

Another finding, on the other hand, is that classifying adjectives allow a parti-

tive pronoun only in French, in contrast to Dutch. In Dutch and German, an

elided noun is acceptable, but not in standard French.

Convergence and divergence 801

In terms of structure, building on Ihsane (2013), we have proposed that

different layers of the nominal structure correspond to different elements in the

languages under study. This can be summarized as follows:

(53) a. + RefP = definite pronoun: les (Fr.), sie (Ger.), ze (Du.), cf. (50)

b. - RefP = en (Fr.), welch- (Ger.), possibly ze (Du.), cf. (49)

c. FP

(de)

24

= en (Fr.), er (Du.), in quantified examples, cf. (51)

d. FP

(de)

= en (Fr.), with a classifying adjective, cf. (52)

An interesting finding of this paper that deserves more research is the different

acceptance rate of the various definite pronouns in non-referential contexts in

German. For Dutch it might be furthermore investigated if, in regional varieties,

the use of er in non-referential contexts is accepted.

Acknowledgements: We would like to thank Gabrielle Hess, Liliane Klaey, Thom

Westveer and Richard Zimmerman, who helped us translate our French test into

German. Our thanks also go to Elisabeth Stark and Jasmin Pfeifer, who helped us

to pilot the test, and to all the participants. The second author gratefully acknowl-

edges the support of the University Research Priority Program “Language and

Space” and of the Romanisches Seminar at the University of Zürich as she was

working on this article.

References

Aguilar-Guevara, Ana & Joost Zwarts. 2011. Weak definites and reference to kinds. In Li Nan &

David Lutz (eds.), Proceedings of SALT 20, 179–196. Cornell University, Ithaca, NY: CLC

Publications.

Audring, Jenny. 2009. Reinventing pronoun gender. Utrecht: LOT publications.

Barbaud, Philippe. 1976. Constructions superlatives et structures apparentées. Linguistic

Analysis 2(2). 125–174.

Barbiers, Sjef. 2005. Variation in the morphosyntax of ONE. Journal of Comparative Germanic

Linguistics 8. 159–183.

Barbiers, Sjef. 2017. Kwantitatief ‘er’ and ‘ze’. Nederlandse Taalkunde 22(2). 163–187.

Bauche, Henri. 1951. Le langage populaire. Paris: Payot.

Bennis, Hans. 1986. Gaps and dummies. Dordrecht: Foris Publications.

Blume, Maria & Barbara Lust. 2016. The grammaticality judgment task. In Maria Blume &

Barbara Lust (eds.), Research methods in language acquisition: Principles, procedures,

and practices, 155–164. Berlin & Boston: De Gruyter Mouton.

Borer, Hagit. 2005. In name only: Structuring sense I. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

24 Cf. the discussion around (51).

802 Petra Sleeman and Tabea Ihsane

Bouchard, Denis. 2002. Adjectives, number, and interfaces. Amsterdam: Elsevier.

Carlier, Anne & Ludo Melis. 2006. L’article partitif et les expressions quantifiantes du type peu

de contiennent-ils le même de? In Georges Kleiber, Catherine Schnedecker & Anne

Theissen (eds.), La relation partie-tout, 449–464. Louvain & Paris: Peeters.

Cinque, Guglielmo. 2010. The syntax of adjectives: A comparative study. Cambridge, MA: MIT

Press.

Corblin, Francis. 1995. Les formes de reprise dans le discours: anaphores et chaînes de

référence. Rennes: Presses universitaires de Rennes.

Corver, Norbert, Marjo Van Koppen & Huib Kranendonk. 2009. Quantitative er: a new micro-

comparative view on an old puzzle. Paper presented at the 24th Comparative Germanic

Syntax Workshop. Brussels: University of Brussels 27–29 May.

Delfitto, Denis & Jan Schroten. 1991. Bare plurals and the number affix in DP. Probus 3.

155–185.

Fodor, Janet & Ivan Sag. 1982. Referential and quantificational indefinites. Linguistics and

Philosophy 5. 355–398.

Glaser, Elvira. 1993. Syntaktische Strategien zum Ausdruck von Indefinitheit und Partitivität im

Deutschen (Standardsprache und Dialekt). In Werner Abraham & Josef Bayer (eds.),

Dialektsyntax,99–116. Opladen: Westdeutscher Verlag.

Gross, Maurice. 1973. On grammatical reference. In Ferenc Kiefer & Nicolas Ruwet (eds.),

Generative grammar in Europe, 203–217. Dordrecht: Reidel.

Haeseryn, Walter, Kirsten Romijn, Guido Geerts, Jaap de Rooij & Maarten C. van den Toorn.

1997. Algemene Nederlandse spraakkunst [Dutch reference grammar]. 2nd edn.

Groningen: Martinus Nijhoff.

Hendrick, Randall. 1985 The distribution of the French clitic en and the ECP. In Larry D. King &

Catherine A. Maley (eds.), Selected papers from the XIIIth Linguistic Symposium on

Romance Languages, Chapel Hill, N.C., 24–26 March 1983, 163–186. Amsterdam &

Philadelphia: John Benjamins.

Ihsane, Tabea. 2008. The layered DP in French: Form and meaning of French indefinites.

Amsterdam & Philadelphia: John Benjamins.

Ihsane, Tabea. 2013. En pronominalization in French and the structure of nominal expressions.

Syntax 16(3). 217–249.

Kayne, Richard. 1977. Syntaxe du français: Le cycle transformationnel. Paris: Editions du Seuil.

Kester, Ellen-Petra. 1996. The nature of adjectival inflection. Utrecht: Utrecht University

dissertation.

Kranendonk, Huib. 2010. Quantificational constructions in the nominal domain: Facets of Dutch

microvariation. Utrecht: LOT Publications.

Kupferman, Lucien. 2001. Quantification et détermination dans les groupes nominaux. In Xavier

Blanco, Pierre-André Buvet & Zoé Gavriilidou (eds.), Détermination et formalisation,

219–234. Amsterdam & Philadelphia: John Benjamins.

Lagae, Véronique. 2001.

J’en ai lu deux, de livres: les structures à détachement de forme de N.

In Dany Amiot, Walter De Mulder & Nelly Flaux (eds.), Le syntagme nominal: Syntaxe et

sémantique, 215–231. Arras: Artois Presses Université.

Lamiroy, Béatrice. 1991. Coréférence et référence disjointe: les deux pronoms. En. Travaux De

Linguistique 22. 41–65.

Longobardi, Giuseppe. 2001. The structure of DPs: Some principles, parameters and problems.

In Marc Baltin & Chris Collins (eds.), The handbook of syntactic theory, 562–603. London:

Blackwell.

Convergence and divergence 803

Milner, Jean-Claude. 1976. Réflexions sur la référence. Langue Française 30(1). 63–73.

Milner, Jean-Claude. 1978. De la syntaxe à l’interprétation. Paris: Editions du Seuil.

Muysken, Pieter & van Riemsdijk. Henk. 1986. Features and projections. Dordrecht: Foris.

Pollock, Jean-Yves. 1998. On the syntax of subnominal clitics: Cliticization and ellipsis. Syntax

1(3). 300–330.

Ronat, Mitsou. 1977. Une contrainte sur l’effacement du nom. In Mitsou Ronat (ed.), Langue,

153–169. Paris: Hermann.

Schutter, Georges de. 1992. Partitief of kwantitatief ER, of over de verklaring van syntactische

variatie [Partitive or quantitative ER: On the explanation of syntactic variation]. Taal En

Tongval 44. 15–26.

Sleeman, Petra. 1993. Noun ellipsis in French. Probus 5. 271–295.

Sleeman, Petra. 1996. Licensing empty nouns in French. The Hague: Holland Academic

Graphics.

Sleeman, Petra. 1998. The quantitative pronoun er in Dutch dialects. In Sjef Barbiers, Johan

Rooryck & Jeroen van de Weijer (eds.), Small words in the big picture: Squibs for Hans

Bennis, 107–111. Leiden: Holland Institute of Generative Linguistics.

Sleeman, Petra. 2013. Deadjectival human nouns: conversion, nominal ellipsis, or mixed

category? Linguística: Revista De Estudos Linguísticos Da Universidade Do Porto 8.

159–180.

Sleeman, Petra & Tabea Ihsane. 2017. The L2 acquisition of the French quantitative pronoun en

by L1 learners of Dutch: Vulnerable domains and cross-linguistic influence. In Elma Blom,

Jeannette Schaeffer & Leonie Cornips (eds.), Cross-linguistic influence of bilingualism: In

honor of Aafke Hulk, 303–330. Amsterdam & Philadelphia: John Benjamins.

Strobel, Thomas. 2013. On the spatial structure of the syntactic variable ‘pronominal partitivity’

in German dialects. In Ernestina Carrilho, Catarina Magro & Xosé Álvarez (eds.), Current

approaches to limits and areas in dialectology, 399–435. Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge

Scholars Publishing.

Strobel, Thomas. 2016. Indefinite-partitive pronouns in the dialects of Hesse. Paper presented

at the workshop Partitivity and Language Contact, University of Zürich, 25–26 November.

Veenstra, Alma, Sanne Berends & van Hout. Angeliek. 2010. Acquisition of object and quanti-

tative pronouns in Dutch. Kinderen Wassen Hem Voordat Ze Er Twee Meenemen. Groninger

Arbeiten Zur Germanistischen Linguistik 51. 9–25.

804 Petra Sleeman and Tabea Ihsane